18 – New Year and the Lashly Mountains

To circle round the head of any major outlet glacier is an exercise to be avoided if possible, as concentric crevasses are likely to ring the Plateau edge and as Sir E found in the Tractor Party, they may extend inland from really major glaciers for a hundred miles or so. Indeed, Amundsen got into bad trouble in 1911 by making direct from the upper Axel Heiburg Glacier towards the Pole and finding himself in what he called “The Devil’s Ballroom”, a trough of broken ice extending into the Inland Ice from Liv’s Glacier.

To circle round the head of any major outlet glacier is an exercise to be avoided if possible, as concentric crevasses are likely to ring the Plateau edge and as Sir E found in the Tractor Party, they may extend inland from really major glaciers for a hundred miles or so. Indeed, Amundsen got into bad trouble in 1911 by making direct from the upper Axel Heiburg Glacier towards the Pole and finding himself in what he called “The Devil’s Ballroom”, a trough of broken ice extending into the Inland Ice from Liv’s Glacier.

However, the Taylor does not drain much ice and we had remarkably few problems. We circled around keeping west of the main icefall on the Plateau edge, but there was another even further west leaving us in some doubt as to which was the one down which Scott, Lashly and Evans fell in 1903. For some reason I remember not, we had decided to drop down onto a glacier which joins the Taylor from the south, which flows north between the Lashly Mountains and Mount Feather. It had a completely undetectable saddle with the Skelton to the south, gave access to mountains on both sides and was lower and more sledgeable than the Plateau itself on the west of the Lashlys.

Now the icefall mentioned above is probably caused by a dolerite sill, and actually continues south and joins the Lashly Mountains and we had to descend it somewhere. About halfway between the Taylor proper and the Lashlys, we pointed downhill down a steepish but unbroken slope. It proved to be less unbroken than we might have wished and the pace got faster and faster and dogs began dropping in through snow-bridges being yanked out again by their traces.

“Oh, hell!” cried Richard, “Let’s take it straight!” and we tucked skis into the sled and ran, clinging to handlebars, giving the sled a mighty heave over collapsing bridges, and with a whoosh and a roar we were soon down on the flat once more, and joined by the others. Those sort of risks, while fun at the time, are quite unjustifiable and sooner or later like the bucket going once too often into the well, one comes to grief. We were showing signs of getting slap-happy, familiarity breeding a good-deal of contempt.

We rested a few minutes, laughing ruefully at this bit of quite dicy going and then pressed on south a little way before camping about a mile or two from the foot of the Lashly’s which rose about 3000 very steep feet to our west. A short run next day saw us under what appeared to be an anticline in the Beacon on the face of the Lashlys on our right, actually two giant tilted sandstone blocks floated up by a dolerite intrusion. Guy and I camped by a litter of moraine while the two sleds went on south to bring more supplies from Plateau Depot which could have only been fifteen miles or so further on. To our vast surprise, at this high altitude, we found more Devonian Fish in the Beacon, how could they be so high up? We must be thousands of feet above the base of the sandstone, it must be upfaulted we decided.

The North Lashly was of dark dolerite with odd rhythmic bands and as the clocks struck the witching hour of midnight on New Year’s Eve for 1958, I was rappelling down from near the summit, swinging on a rope belayed by Warren, to collect some samples. As we broke camp, my geological hammer, stuck in snow at the tent door was left behind. Now is a thing lost when you know exactly where it is? We passed south across the whole Skelton Neve to visit nunataks near the Mulock Glacier and we had an enjoyable rock climb on a dolerite peak we called Escalade. It was actually formed of two dolerite sills, and the rock was steep and sound. The sun warmed the rock and we could pull off gloves for better finger holds.

Then back again north and passing east of Mount Feather this time, we began to descend the Upper Ferrar, my preferred route out of the Ferrar of two years before, and we camped beside a vertical castellated nunatak we called Monastery Peak. A couple of six-foot crevasse lids had given way as we came into the upper Ferrar, but we swung south-east and found better going. Time was running out, the Endeavour had arrived in the Sound and some American ships were soon to leave, and on the 4th of Jan.1958 came the news that the Tractor Party had reached the Pole, but it seemed Bunny Fuchs was still hundreds of miles away.

On the 8th we heard that Roy Carlyon and Harry Ayres had climbed Mount Henderson above the Darwin Glacier and seemed to be having a good time. They had turned east from Depot 480 on Dec. 1, and, as we had recently done, approached the mountains from the rear. Their map was the first of the Darwin Hills and of the Darwin and Hatherton Glaciers and the mountains to the north and south. Later they were joined by Cranfield and Sel Bucknell, our cook, and made a fast trip straight down the Darwin to the Ross Ice shelf before being airlifted out. So even cooks and flyboys were able to have some fun dog-sledging and variety is the spice of life. One remembers Sir Clements Markhams chilly response to a librarian of the Royal Society who wished to join an Arctic expedition, “The correct place for a librarian is in the Library!” Or a cook in the galley? A pilot in an aircraft?

The Darwin region is in the height of summer almost a “Dry Valley” area with bare mountainsides, and as recent satellite pictures show, the lower glacier is ice and covered with thaw channels.

Odd snippets of news had been received by radio about Miller and Marsh but it was years before the true nature of their tragedy became plain.

To digress a little into Philosophy, one finds several kinds of people on these affrays. The pure Adventurer responds only to the physical challenge of doing something never done before, to climb the highest mountain, take a jet-boat up the Ganges, cross the Matto Grosso, sail round the world. To be an Adventurer, one need not be a super athlete though one is likely to need a great deal of perseverance and determination, and they tend to be large men. The element of a kind of danger which can be overcome by skill and intelligence must be there, or where is the challenge? Hillary has described himself as an Adventurer, “I have never needed a plethora of scientific excuses to do something I considered worth-while!” The challenge is enough, is it possible to be the first to get to the South Pole with only a few farm tractors? Shackleton was an Adventurer, so was Smith, Mulgrew, Amundsen, Mawson, (perhaps) , Armitage, Francis Chichester, so was Admiral Byrd. The fact that Byrd went home immediately after flying to the Pole and was not even slightly interested in photographing the Queen Maud Mountains, shows he was an Adventurer. Adventurers have a single, difficult objective, climb that mountain, traverse that continent. Most of Bunny’s men were Adventurers, though some, like Ken Blaiklock simply liked the place. How keen David Pratt was in seismic sounding the thickness of the Antarctic Ice sheet I do not know, but one can assume he at least had some genuine scientific interests, as did their geologist

Some Adventurers are also regrettably Publicity Hunters, a charge which I do not think could not be levelled at any member of TAE. To some degree, publicity hunting is forced on many explorers in order to finance their expeditions, and some, Peary and Cook for example and even the great Amundsen himself, at times seemed to think of little else. Amundsen wrote of his relief at finding the Terra Nova carried no radio and of the need to make all speed to Hobart to be the first to claim the Pole, rather perplexing to simple people such as us. Once the Pole had been achieved, Amundsen lost all interest in the place and never even constructed more than a sketch of the Axel Heiberg Glacier area, a task left to Wally Herbert in 1964.

Sir E himself, having reached the Pole lost all interest in it and flew home and was somewhat lukewarm about continuing support for the Crossing Party. Whether Sir Bunny felt a major loss at not achieving the First to the Pole By Tractor he has never bothered to discuss, but there remained the second prize, the First Across the Continent with which he was presumably content, a satisfactory division of spoils.

Latter-day Adventurers may deliberately limit their methods, so as to enhance the physical challenge, to travel from de Surville Cliffs to the Bluff, but, on foot: to climb Everest, but, without the aid of oxygen: to get to the Pole, but overland, not by air. On the other hand the scope of the Adventure may be strictly limited, as the so-called “Adventure Treks” where parties are guided, meals cooked, and generally waited on. Then we have our sail-training ships, such as the “Spirit of Adventure” where the poor trainees are not allowed aloft and may not even learn how to use a winch. Recently there have been much-publicised trips to both poles with dogs or on foot during which aeroplanes daily bring in more supplies, fuel, or people until one wonders what the point of the whole exercise can possibly be! Even the old Sourdoughs dog race from Fairbanks to Nome is now won by the contestants who can afford daily airlifts of fresh dogs, so it bears about as much relation to an enactment of the old gold-rush traverse as it does to a circus.

Adventurers are followed by mere Competers whose aim is the rather childish one of completing some activity in less time than that taken by some other Competer, to run a mile in a tenth of a second less time, to jump a millimeter or two higher, to sail a ship, not where no man has ever been, but around the buoys a half-boat length ahead of a rival.

Then there is the true Explorer, who needs an intellectual component and the satisfaction or at least the possibility of achieving new knowledge. To find a new route, a new pass, a new rock, a new valley, glacier or mountain, a new animal species, new farmland, new lands or islands, to be a explorer or pioneer is an urge and motivation we have had for at least a million years. Some explorers are content with geographical discovery as Burton and Speke, others are prepared to come to a remote region to carry out some specialised study though regarding the isolation and necessary travel as a confounded nuisance.

The purely intellectual science explorer may never leave the confines of a single room but may discover new equations in Pure Mathematics, or arrive at a theory of galactic attraction, or of the atomic nucleus! The first type of explorer is satisfied to have found a way through country seen by no-one else, the second feels compelled to map it in meticulously, the third to have found a concept never before enunciated.

In the old days there were also the Merchant Adventurers who sailed to far Cathay in leaking tubs in the hope of not only adventure, but piling up a great profit. They graded laterally through quasi-legal Gentlemen of Fortune into those prepared to take extremely short short-cuts on the road to wealth, the Pure Pirates, who are still with us, though disguised in three-piece suits.

As an explorer, Brookes, for example was prepared to sledge a couple of thousand miles to accomplish the survey of new country, but he was not interested in sledging pointlessly across the continent, nor was I. To take a few hours off to dash up a virgin mountain gives a brief sense of elation but it accomplishes little except that one may see some new country which adds a little cream to the cake, but one would not toil for years in order to potter up a few unnamed peaks. At the end there is only satisfaction in knowing that now one knows, what is there, which valley saddles with which, how old the rocks are, how deep the ice on the ice-cap is. Brookes was later to say,

“It was a job that needed doing, a job that was interesting and demanding, and a job I think we did well!” There are few more stirring sights than to see, in the far blue distance, hull down on the horizon, the tops of yet unknown peaks and land. Scott was of this type, one only has to read his serious calculation of the amount of ice flowing off the ice cap, his real interest in biological problems, the fact that he, Bowers, Wilson and Qates refused to throw away their fossil samples. Personally I have more respect for Scott than for Shackleton who was a mere Adventurer.

What drove Bert Crary to return year after year to do dangerous and boring traverses, but building up an exciting picture of our only true Polar Ice Cap? Certainly not a spirit of Adventure only, but this aspect was there or he would have found some pedestrian problem near home and reachable by car. Crary was a scientific pioneer and explorer. Needless to say, Adventurers, Explorers and Competers have remarkably little understanding of each other’s motives! Was George Marsh, that most intellectual of men, merely a Competer, out to break Amundsen’s sledging record? No, because to George, sledging was an art-form to be practised and improved and perfected, to beat Amundsen was merely the test of his perfected machine. Miller was an explorer, his sights set on new mountains and new land. At D700, their duty done to the mere Adventurers, Miller and Marsh set off due east towards their survey area, the completely unknown ranges west of the sketchily known Queen Alexander Range. Amongst our generally rough-spoken company, they were an unusual pair.

“Would you care for some more pemmican, George?”

“No, no! My dear chap! After you!” Hillary refused their request for a couple of tractors to lay a food depot a hundred miles closer to the mountains, later he was to say;

“I looked on this as a well-meant attempt to divert me from the Pole!”

Instead, Cranfield flew them in more supplies, a round flight of over a thousand miles! Hillary was quite wrong, obviously he could not see, that to Miller to go on to a meaningless point on the Plateau, even one termed The Pole was trivial, compared to the opportunities to map some new land, and Miller and Marsh sledged on to their goal. Eight hundred miles or more from Base their first unknown mountain tops hove up reluctantly above the horizon, a goal many have died for rather than turn back at this point. It was the summit of Mount Markham, which at 15,000 ft was then thought to be the highest mountain in the continent and they saw it the same evening as we, six hundred miles north saw old friend Shapeless as we too approached from the Inland Ice.

On the 7th of January, Hillary, having been asked by Fuchs to build up more fuel at D700 (which Sir E suspected might be merely another design to prevent their going on to the Pole), did not hesitate, he went on and ordered Marsh and Miller back to D700 to operate the radar emitter and act as ground support to the flight movements. Their whole field season after sledging nearly a thousand miles and spending two years in preparation, was to last 16 days, and I at least can imagine the tension in the tent when this message was received!

Personally, I would have had little hesitation, the tractors had allegedly been added to the Depot laying parties merely to strengthen it and free the dog parties for the very work they were now being denied, my answer would have been “No!” In any case it could have been delayed another two weeks until the dogs were on their way home. On the 6th of January, John Lewis and Gordon Haslop flew the larger Otter from Shackleton Base over to Scott Base and with the safety margin of two aircraft, what was the need of more fuel at this point? In any case it was not used, there being forty drums to spare when the Crossing Party arrived at McMurdo on the 2nd March.

Personally, I would have had little hesitation, the tractors had allegedly been added to the Depot laying parties merely to strengthen it and free the dog parties for the very work they were now being denied, my answer would have been “No!” In any case it could have been delayed another two weeks until the dogs were on their way home. On the 6th of January, John Lewis and Gordon Haslop flew the larger Otter from Shackleton Base over to Scott Base and with the safety margin of two aircraft, what was the need of more fuel at this point? In any case it was not used, there being forty drums to spare when the Crossing Party arrived at McMurdo on the 2nd March.

But those two truly great men, Sir J. Holmes Miller and Dr George Marsh having already been denied the slight glamour of pioneering a new route towards the Pole, gave up their field program as well and returned to D700. They were better men than I, (or perhaps more honourably foolish), they never spoke of the matter, nor, except under duress, did they speak to Hillary again. Great men are capable of great follies. There remained only George’s ambitions on the dog-sledging record. At D700 Claydon suggested they board the plane and fly home, but Marsh, removing pipe from mouth, uttered one word, ”No!”

Again, the true worth of J.Holmes Miller was shown, it was no part of his ambition to beat a forty year-old sledging record, but with nothing but encouragement, he sledged along, the whole 700 miles home. The tent had to be erected 35 times more, the primus lit 70 times, 315 dogs had to be harnessed, but, George wanted to do it! Requiescat in Pace!

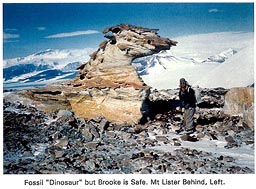

While all this drama was taking place, we simple few carried on. We took empty sleds and rattled down the Ferrar a few miles and over to the north side. We knew that another dry valley, the Beacon Valley lay beyond the hills as yet unmapped and we anchored the dogs and shinned a few thousand feet up what is an extended eastern ridge of Mount Feather. Wind roared past towers on the ridge and drift poured over cols, but suddenly in a saddle there was calm. One rust-stained sandstone tor towering high above our heads looked rather like a sphinx or perhaps a fossil dinosaur, and odd cemented concretions lay about looking like fossil birds nests! This horizon is now called the “Ashtray Sandstone”!

We finally gained a station overlooking the Beacon Valley, with its creeping rock glaciers. Back in camp at 5pm I pulled off my High Altitude boots, which were steaming like porridge pots! An attempt on the south-east ridge of Mount Feather was a failure, we found more Devonian fish remains, but a strong south-west wind was blowing and the ridge exposed so Warren and I gave up. It was a pity as Feather was only 9000ft and has more Triassic rock near the summit, the discovery of which had to wait another twenty years.

We moved south-east to Pivot Peak and from its summit could see that Mt. Lister was only approachable by descending a long way down the Ferrar as there was a tangle of more than twenty miles of hills between its massive peak and the point where we stood. It seemed a nice way to round off the year would be to climb at least one of the major peaks in the Royal Society Range. The radio, which in a rational society would never have been allowed, informed us that the “Greenville Victory” was about to leave for home and was taking some of our people with it, even Harry Ayres and Roy Carlyon, and Sir E had the effrontery to suggest we might like to join them. Somewhat to my surprise, Douglas and Warren both indicated they would go but Brooke and I felt there was much to do yet, and Bunny had only just reached the Pole!

On the 20th. of Jan, Claydon arrived with Taff Williams who had flown across the continent in the Otter with John Lewis, and buzzed about, again having his own ideas as to where we were until more radio comments via Base finally persuaded him to come over to Pivot Peak. We shook hands and our two stalwarts left, taking with them boxes of rock samples which lightened loads.

“Good luck with the shaggy dogs, old Man!” said Douglas. The Beaver had run on a quarter mile into the wind, and its big tail-plane weather-cocked so that even pushing by two men failed to turn her down wind, so we had to run things up by sledge. Claydon took a last photo of the four of us, standing proudly in the sun and drift, it was rather a sad parting, we had made an effective team in spite of our very different temperaments. Apart from an occasional “Damn you,.. “ and “What the hell do you think ...“ we had had few disagreements. I inherited the radio from Douglas, and Gawn made impatient noises when I forgot to switch to “Transmit”.

“Come on, Come on, just because you lost your operator ---.“ From now on it was to be two men and eighteen dogs and fast travelling.

©2007 - may not be reproduced without permission