19 – Two Men, Eighteen Dogs

The Beaver wound up to the unearthly supersonic scream that it always made when performing a perfectly ordinary takeoff and departed from Pivot Peak Camp in a streaming cloud of drift. After four months of being adjusted to a camp-city of two tents, two sledges and 18 dogs on spans, to only see one tent was rather akin to having half of your home town demolished in an air raid. However we were at no stage what you might term emotionally dependent on other members of the party, we tended to talk more to the dogs than to each other.

The Beaver wound up to the unearthly supersonic scream that it always made when performing a perfectly ordinary takeoff and departed from Pivot Peak Camp in a streaming cloud of drift. After four months of being adjusted to a camp-city of two tents, two sledges and 18 dogs on spans, to only see one tent was rather akin to having half of your home town demolished in an air raid. However we were at no stage what you might term emotionally dependent on other members of the party, we tended to talk more to the dogs than to each other.

We sipped tea in the luxury of our bags, by now beginning to smell rather strongly of unwashed humanity.

“Should be able to make better day’s travel with just the two of us, don’t you think?” said Richard. “In Greenland we always said, ‘One man, One team’!”

Actually our loads were less but one man per sledge - gives little margin for error, I was later to find that four men with three sledges was by far the best.

Another Survey station confirmed the difficulty of approaching Lister without descending the Ferrar about 15 miles and we lay on our bags idly discussing the possibility of approaching Mount Huggins at the southern end of the range, from further down the Skelton, by going down to The Landing and turning north. We were not all burned up to make the climb but we both felt that it would be a fitting end to the long season’s travel to climb one of the major peaks in the Royal Society Range none of which had been climbed before.

Getting under way without the help of a second man meant a little more careful planning. Without a man to stand on the trace, the dogs as usual pawing the air and mad-keen to make the first dash of the day meant a tricky little interval, as with the sled all packed, the dogs in-spanned and held by an ice-axe in the snow through the lead-dogs trace, the wire dog span still had to be dug up, coiled over the tent poles on the front of the sled, the shovel tucked in, all the time to a soothing

“Lie down dogs, quiet there, Sis! Down, I say!” When the restraining ice-axe out, there was no keeping up the pretence of control any longer, and we were away at the usual mad gallop. The driver, of course, had to throw himself aboard the sled as it flashed by, there being few more ridiculous situations than to be left standing alone on a vast reach of snow, as your sledge and spirited team vanish from sight over a distant rise, you being five hundred miles or so from home at the time!

Without the extra tent, sleeping bags and gear the sleds were undeniably lighter and we dashed on, until rising ground meant pulling out ski and kicking them on with the practice of years. It was a gorgeous day, the mountains rolled by as we swung south and east towards the Upper Staircase in the Skelton, and as the descent steepened I let go of the sled and slalomed alongside, though in some places I had to use the brake. Quet, my lead dog was leading well and though I still had a load of 636lb, the boys were too fast for Richard’s team and I had to stop six or eight times to let him stay ahead. We saw not a single crevasse

close to our route, although we must have passed over many found at other times by tractors. Only a month later the Crossing Party was to gripe about -38 temperatures and 50 knot winds at this same spot!

We camped at Stepaside Spur, an odd complex of pink granite dikes in dolerite, but found next day 1300 feet above camp the wind to be too strong for surveying. From there we went on down to the Landing and then swung north up a tributary glacier directly toward the great glaciated peak that had reminded me of our own Mount Tasman three years before. A great bluff stretched in front of it sloping down to the west, and ice cascades pour down into the trench-like valley we were ascending. We called it “Rampart Ridge”.

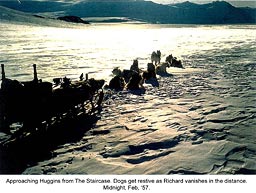

It was going on midnight and the low sun behind us etched the sastrugi, Brooke was half a mile ahead vanishing periodically in the drift, and when I paused for a photo the dogs were edgy and soon dashed on with such vigour that we caught up before camping. On up the valley the snow deepened and the mountains closed in and lowered over us in an almost threatening way. We made a depot of half our Stores, but even then the soft snow slowed us and we finally camped again below a steepish pitch.

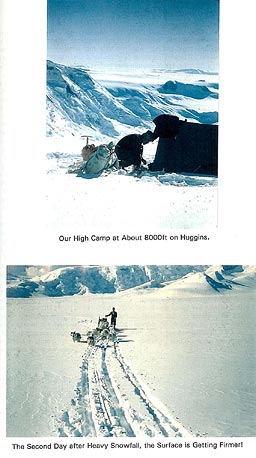

Richard’s dogs started a fight when he was laying out his span and that started my boys off, controlling fights was undoubtedly more difficult with only two men, outnumbered by 18 dogs. In the night an avalanche thundered and boomed off the ice-face opposite and cloud bulked over the hills as we lay between Huggins on the right and the slopes of Hooker to the left. We packed the Meade tent, gave the dogs a double feed and warning them to behave, pushed on on ski.

In places skins would have been a help but we made perhaps three miles and a couple of thousand feet in height before putting up the little Meade. The next morning (the 26th Jan.) drift was blowing off the tops but as the morning wore on, the wind died and some fairweather cumulus drifted up over the Col between Huggins and Hooker.

In places skins would have been a help but we made perhaps three miles and a couple of thousand feet in height before putting up the little Meade. The next morning (the 26th Jan.) drift was blowing off the tops but as the morning wore on, the wind died and some fairweather cumulus drifted up over the Col between Huggins and Hooker.

We got away at 6am and plugged in soft snow up a steep face which hardened rapidly so we then took turns in kicking steps in crampons. Getting too steep to be comfortable, we looked left to a corniced ridge which looked easier. Moving over there was an oath from behind as one of Brookes crampons broke, the steel seeming to get very brittle in the cold.

“Shall we give up?” he asked. I fished about in my pack, without speaking, having encountered this problem before and produced a length of rawhide and did a repair job. I cut over to the cornice and then with a bit of whittling by Richard who held on with one hand and cut with the other, to get, as he explained, some practice for the Himalayas, we were soon up and over, though even that short pause was enough for all feeling to have gone out of my feet. Soon we were on the main divide ridge at 10,700 feet, above mighty cliffs that face the distant McMurdo Sound and Erebus steamed faintly through the haze perhaps eighty miles away.

Sandstone ledges and snow alternated, the yellow and brown rock being rather crumbly, I do not remember any dolerite layers. The summit was a broad snow and rock dome and even with down jackets on at 12,700 ft by aneroid, we rapidly felt cold, I suppose it was about twenty or thirty below. North, the summits of Rucker and Lister appeared fitfully between clouds and south, also largely obscured, was Harmsworth Peak of a year before.

We soon set off home, descending into the col between Huggins and Hooker, dropping over the cornice and plowing down to the tent. After a quick brew of soup we swung packs on and skiied down to the pyramid tent and the dogs in an hour or so, to find a positive shambles of half-pulled out spans and signs of dog fights. We beat everyone indiscriminately, and having restored order if not law, retired into the pyramid. We called up Base on the radio and in our miserable dits and das tried to convey the fact that we had climbed the mountain. Finally we heard Hillary’s voice:

“Glad you climbed it,” said he. “Who got to the top first?” and we tapped out the inevitable “almost together!”

Then came the snow, it fell in large flakes, more like as in the Alps than the Antarctic, it piled upon us and buried sledges, it crumped and boomed off the slopes and precipices, and still it fell. After two days there was a lull and a little visibility and we set off even though on skis it was still knee deep. The dogs floundered, the sleds rolled over and after we picked up our buried depot the extra weight slowed us to a crawl. We took turns in breaking trail, the second man sitting on the first team to allow the trail-breaker a few hundred yards start, then starting them off before dashing back to the second team to get them moving, and yelling heartily at all eighteen dogs. Within minutes even with a hundred-yard start the panting behind would grow loud and paws would be scratching on ski, and the panting would grow so distressed that we would all collapse for another break. The sheer willingness and guts displayed by the dogs exceeded our own. We camped after all of about five miles and next day broke trail again. As we emerged from the valley the new snow thinned and suddenly Richard swerved a little to Larboard and stopped, and there in the snow was the tip of a bamboo and underneath three ration boxes and some kero.

“Dumped them here a year ago,” Richard explained. Once over the Lower Staircase we travelled even faster heading towards Tricouni. At its base there was no new snow, just rocks projecting through ice. I left the dogs, and, hammer in hand climbed up to get samples. As I hammered I heard panting and scratching, and there they were, eleven lovable and brainless nitwits, scrabbling towards me dragging the. sled and all, up a mountain side!

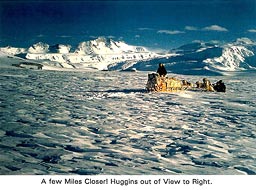

The next day I suggested to Brooke that I go in front, Richard was very fond of leading but one doesn’t learn much, simply trailing behind. He agreed somewhat reluctantly and we set off. It soon became obvious that my lighter team was in fact much faster and every few miles I found Brooke becoming hull-down astern and I would have to stop. I delayed too long and his team also having to stop, milled around and tangled traces.

The next day I suggested to Brooke that I go in front, Richard was very fond of leading but one doesn’t learn much, simply trailing behind. He agreed somewhat reluctantly and we set off. It soon became obvious that my lighter team was in fact much faster and every few miles I found Brooke becoming hull-down astern and I would have to stop. I delayed too long and his team also having to stop, milled around and tangled traces.

“Don’t stop!” called Brooke in an irritated voice, “Keep going!” which was all very well but after ten miles he was at least two miles behind. The medial trough was icy and the drift so thick one could not see the ground or ice rather, but we moved south where I knew was good snow and camped only two miles from our old “Boot Hill”.

From Tricouni to Skelton Depot is only about 35 miles but we were in no great hurry. I kept to the south side past Anthill and Bareface Bluff because I knew there would be glare-ice at the centre and there should be no crevasses, but the surface had changed, there was more ice and in fact near where Heine had “heard Angels” a year before, there could now be seen crevasses as much as three feet wide. An occasional bridge fell in but nothing dangerous and I swung out again towards the centre and better going. In general one should stick to the middle of glaciers, and over my shoulder I could see Richard in the distance cutting out of the danger area also but four months before Marsh and Miller had had many capsizes out there on the wind-fluted ice and the tractors had broken through crevasse-lids many times.

We had agreed to camp near Teall Id and I had spanned dogs and had the tent up before Richard arrived, very grumpy and out of sorts. He simply hated travelling second and being left behind was not at all soothing.

“I’m bloody chocker with the way you led today!” he said without any preamble, “You went far too far to the right and led us into crevasses!” I could only protest that there had not seemed to be any there the year before, which did not help and we had an unusually silent meal of our usual sickening pemmican, I raised the matter of our sledging on home instead of being ignominiously carried in by Beaver as was planned, but Brooke was not in a sympathetic mood.

Next day was clouded over and we stayed around camp resewing clothes and ski bindings and trying in vain to contact Base on the radio to tell them where we were. Suddenly Richard spoke.

“Look, we had better have this out,” he said abruptly. “I suppose there are things about me that annoy you and I well know there are things about you that annoy me!” This seemed so likely that it had seemed hardly worthy of comment, but I had always felt that Brooke’s many virtues far outweighed any possible oddities of character.

“Like what?” I said, unwisely.

“Well, you don’t always pull your weight!” This was too much!

“I what!” I had realised years ago that Brooke was quite sensitive to defects in his travel companions and for two years I had made sure, without being obvious, that it was me who was out of the sleeping bag first in the morning, that it was my gear that was out of the tent door first, that when it was my turn in the tent, he got his air mattress inflated and his bag laid out to air, which was not usually done. We had taken all of five forced days off in the 128 that had now elapsed and I had always let his survey program take precedence though it meant holes in the geological program at times.

“Like when for example?” I said feeling somewhat sick in the gut. All this seemed so unnecessary.

“Like the first time we camped together and you didn’t take your first turn cooking!” I turned away, too disgusted to speak. A long time ago when we had first shared a tent, Richard had fussed about playing the Old Antarctic Traveller, in fact competing to show how it was done. I had smiled internally and let him, but after he cooked two meals in a row, it was obvious he was feeling martyred and I had never let it happen again.

“What sort of a man could only remember a thing like that?” I thought, wondering. We must have sledged over 2000 miles together, we must have walked and skiied another thousand, we had climbed over forty mountains and this man remembered only the fact that on one single night he had put on a meal when it wasn’t his turn! I had come to respect Richard for his unswerving drive and taken it for granted the feeling was mutual. What sort of a man could forget all we had been through? Suddenly Brooke realised what he had just said, and he put out a hand.

“Oh, my God!” he said appalled. “I didn’t mean that, I’m sorry, I don’t know what came over me .

“Its all right, forget it,” I said wearily, but it was a great pity. Years of joint effort and dangers shared had built up a rapport which could never be quite the same again.

We climbed Teal Id over the greywackes, and reoccupied the station and I measured some folds and structure in the rocks. By midday the temperature was a degree above freezing and at 6:30 pm we ran over to Skelton Depot, sitting on our sledges without anoraks, the dogs legarthic in the warmth though a down glacier breeze was getting up. In the tent it was still silent and Richard suddenly burst out,

“I say, do forgive me, I feel I’ve ruined the whole party !“ I shook his hand.

“It doesn’t matter!” said I. “I understand!” I have never heard of a Polar field party grinding away the way we had, and on Richard had come most of the responsibility. We perhaps had too great a conceit of ourselves, others might crack up under continuous strain, us never, we could go on for ever if need be, one wears a task down but we forgot that even diamond is abraded in time. It was a great pity. I would have loved to have completed the long journey by sledging home across the Barrier, out to One Ton, round Minna Bluff, White Island and Corner Camp, instead of ignominiously being carted home by plane, but now it seemed that the journey would not be so pleasant. On the 5th of February, we told Base by radio that the cloud base was 5000ft but the Beaver did not take-off until midday. The weather worsened and at 12.30 I was on the morse key again to tell them the cloud was on the deck. We heard the motor of the Beaver for a moment as Bill Cranfield turned for home.

The next day the cloud base was at 7000ft and we could see Minna Saddle but Claydon refused to fly so we kept up hourly reports all day. At 2200 Cranfield came in in whiteout conditions and landed in a flurry of snow within yards of the spanned dogs, which gave him a good ground marker, showing how cunning our flyboys were getting, and our long months of isolation were gone for ever.

©2007 - may not be reproduced without permission