17 – The Northern Party Sets Out

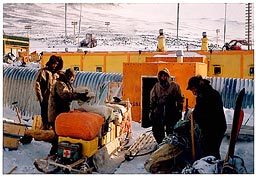

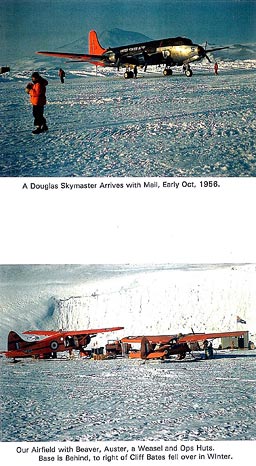

On the 1st of October our isolation was broken by the arrival of an R4D Skymaster and a P2V Neptune carrying mail. We went over to the field in a Weasel to get the mail and were startled by the new, tanned and shaven faces compared to the scruffy, pale and bearded American Old Hands who were wearing fluorescent pink ribbons round their ankles. This of course was a device to encourage a Newchum to ask, “What are the ribbons for” so the O.A.E. (Old Antarctic Explorer) could give a contemptuous look and reply

On the 1st of October our isolation was broken by the arrival of an R4D Skymaster and a P2V Neptune carrying mail. We went over to the field in a Weasel to get the mail and were startled by the new, tanned and shaven faces compared to the scruffy, pale and bearded American Old Hands who were wearing fluorescent pink ribbons round their ankles. This of course was a device to encourage a Newchum to ask, “What are the ribbons for” so the O.A.E. (Old Antarctic Explorer) could give a contemptuous look and reply

“To keep the snow snakes from gittin’ up yer pants ‘course, you mean you don’t have any?” Americans went in for this kind of humour! On the 4th we cleaned out our cubicles and stored our gear in the sledgeroom and at 11am went down to the dog lines bearing a tiny “Personal bag” containing a book, a sewing kit, a diary, and a spare pair of gloves and socks. Other than that we had what we stood up in plus a spare anorak and jersey to be given to anyone of the party who lost one.

“See you later!” I said to one man immersed in a book in the Mess.

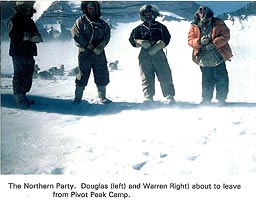

“Oh, are you leaving?” said he without looking up. It was actually 25 years before I saw him again! The sleds were already packed, Cranfield alone came down to help hitch up the dogs and with the surety of long practice we were away with a yip and a howl, our departure being slightly marred by finding the essential wire span for the dogs had been left at the lines so we had to swing round in a circle to retrieve it. However, a journey begun badly ends well, so they say, and soon we were scampering off again, passing Douglas and Warren, then dropping skis one at a time and kicking feet in, a fast days travel of 18 miles by 3:30 to the Dailey Islands with Douglas and Warren only slightly behind, a good day’s start. In the tent we sipped cocoa.

“God!” Richard suddenly burst out, “I thought we were pretty casual in Greenland, but at least someone said “Goodbye” to you when you left for a thousand-mile journey!”

“God!” Richard suddenly burst out, “I thought we were pretty casual in Greenland, but at least someone said “Goodbye” to you when you left for a thousand-mile journey!”

I thought about this. “It’s a kind of inverted flattery,” I said. “If you make a fuss wishing people luck, it implies you are not sure they’ll make it which is a kind of insult.” but Richard was not entirely convinced. There is no doubt New Zealanders are indeed a pretty dour lot!

Next morning, we found some of the ties of the tent poles needed retying and Douglas and Warren set off before us, passing close by, which started a fight amongst our dogs. Joe suffered a badly bitten eye which gave us some concern, but he recovered though he lost the sight of that eye, huskies being tough. By 2:30 we had covered 21 miles to Butter Point on a chilly day so that sometimes I ran for a mile or two.

We killed a seal for the dogs and I raided the food dump and made a revolting hash of beans, onions, sultanas and boiled seal. Twenty more miles of pressure ridges across the bay of New Harbour and we rounded Gneiss Point and the beginning of our field work. Again there was a food dump left by a tractor party a few weeks before. From this Point we wanted to head inland to get as close to the Dry Valleys as possible, in fact we were immediately opposite the Wright Valley but separated from it by about ten miles of almost level Piedmont, the odd coastal plain which is covered by an ice-slab.

We found a ramp up off the sea-ice and dug out a road and were soon up and over the ice bulge. I stepped over a narrow crevasse but behind there was a yelp as Fido, Dismal and Joe fell in. With hardly a pause, Richard tipped the sledge over and we hauled out Fido, but the other dogs had gone, their harness rings having broken with the jerk. Richard turned to me looking stricken,

“My God! I’ve lost my two best dogs, no, wait a minute, can I see them?” and there they were on a thin bridge of snow 33 feet down. I pulled out the climbing rope, tied a bowline onto the sled and passed him the other end, and, passing it through a karabiner, Richard kicked over the edge without a word and I walked forward, lowering him down. Douglas peered down the hole and raised a hand when the dogs were reached. They actually had their legs hanging through the thin bridge and Brooke hooked an arm through the harnesses. A second rope went down , up came the dogs, and then Brooke, Douglas giving powerful heaves on the second line. Dismal and Joe celebrated their return by sailing into the others who by husky logic must have been responsible!

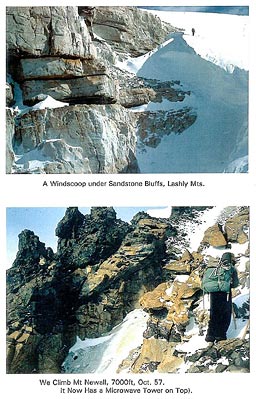

Soon we were on our way again and made 8 miles across rolling snow and camped by a limestone knoll. Drift and zero visibility gave us a make and mend day but another 1 1/2 hours brought us as far as we could take sledges. The rock ledges on the mountain were capped with iron-hard blue ice and snow powder sifted from every exposure but the view from the top of Mt Newall, at 6,700 feet was right up the Wright Valley, entirely bare of ice but with a dusting of snow. Thirty years later there is a VHF radio repeater station on top of Newall!

Soon we were on our way again and made 8 miles across rolling snow and camped by a limestone knoll. Drift and zero visibility gave us a make and mend day but another 1 1/2 hours brought us as far as we could take sledges. The rock ledges on the mountain were capped with iron-hard blue ice and snow powder sifted from every exposure but the view from the top of Mt Newall, at 6,700 feet was right up the Wright Valley, entirely bare of ice but with a dusting of snow. Thirty years later there is a VHF radio repeater station on top of Newall!

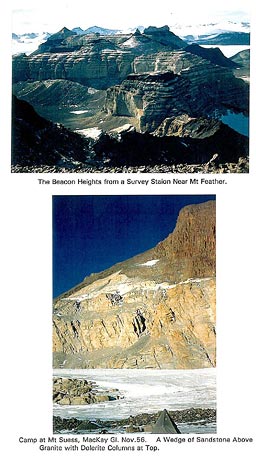

To the west and north there were three large mountains of about 10,000 feet, one being the Shapeless mountain we had seen from the edge of the Plateau two years before. Now you can’t name mountains K2, K3, K4 etc and we had some debate as to what they should be known as.

“Oh, for Heaven’s sake!” burst out Douglas after some inconsequential debate. “Call that one Shapeless, the one with the straight summit ridge, Tent and the leaning one, Skew Peak!” and so they were called for many years until someone behind a desk renamed them for various politicians and bureaucrats, though I believe Shapeless is still known, unofficially at least by its highly descriptive name! Warren and I cramponed down the north ridge collecting as we went but we made no effort to spend a day walking up the valley, possibly because the cover of moraine litter meant little fresh rock was actually exposed. Later in the middle of summer, Ron Batham with three summer support people; Dick Barwick, Peter Webb and Andrew Packard was helicoptered into the Victoria valley ten miles north and spent several weeks actually in the valleys, their first visitors.

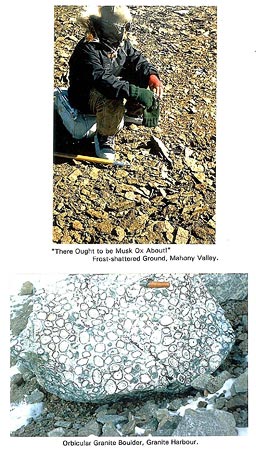

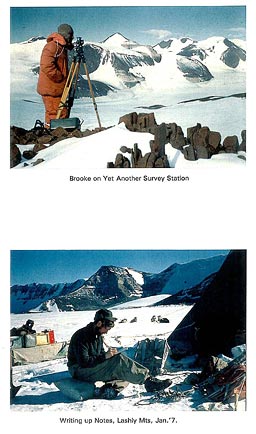

For the next four months the routine changed little, up and away early, sledge ten, fifteen miles, pause for 15 minutes for a greasy biscuit, a piece of chocolate and a pull at the thermos of tea, then another ten or twelve miles, and camp, dig in the dog span, feed the dogs, tent up, food and primus box in, brew up a cup of cocoa, dinner on, a minimum of desultory conversation, write up diaries and field book, and off to sleep, perhaps the easiest task of the day. The next day Brookes and Douglas would usually head for the nearest prominence and set up a survey station, while we other two would walk rapidly from one outcrop to another, collecting samples, sketching the rock distribution, collecting samples. Occasionally a mineral find or some unusual crystals would spur excitement. We traced the margins of the granite intrusions, the occurrence of, the marbles and schists, the folds in the rocks, and we checked them for radio-activity. Much of the best rock was on the steeper bluffs and I shudder to think how many vertical feet we must have covered.

For the next four months the routine changed little, up and away early, sledge ten, fifteen miles, pause for 15 minutes for a greasy biscuit, a piece of chocolate and a pull at the thermos of tea, then another ten or twelve miles, and camp, dig in the dog span, feed the dogs, tent up, food and primus box in, brew up a cup of cocoa, dinner on, a minimum of desultory conversation, write up diaries and field book, and off to sleep, perhaps the easiest task of the day. The next day Brookes and Douglas would usually head for the nearest prominence and set up a survey station, while we other two would walk rapidly from one outcrop to another, collecting samples, sketching the rock distribution, collecting samples. Occasionally a mineral find or some unusual crystals would spur excitement. We traced the margins of the granite intrusions, the occurrence of, the marbles and schists, the folds in the rocks, and we checked them for radio-activity. Much of the best rock was on the steeper bluffs and I shudder to think how many vertical feet we must have covered.

As we passed up the coast, the ice was rafted and jagged pressure ridges rose blue and white, twenty feet in the air but near the land was a perfectly smooth lane a few chain wide, obviously the ice had pulled out from the shore in the Fall and had refrozen giving us a perfect road along which we clattered.

As we approached Cape Roberts with a boulder bank extending out on the southern approach to Granite Harbour, Richard suddenly pointed;

“Hello!” he cried. “Look, a cairn and a marker!” There was indeed an ancient bamboo standing and buried in snow and rock beneath was a black camera-plate changing bag, belonging to Debenham, a handsome Norwegian jersey of Tryggve Gran’s, and a pair of socks, matted with reindeer hair, left here in 1911 when Taylor’s party was forced to retreat as far as The Stranded Moraines along the Piedmont when the “TerraNova” failed to pick them up. Their cameras and samples were picked up later and the food they left saved the lives of Campbell’s Party on their retreat down the coast after their winter in the snowcave at Terra Nova Bay.

I later wrote to Sir Frank about the find and received a charming letter in response;

I later wrote to Sir Frank about the find and received a charming letter in response;

“When we hear of the amazing amount of ground covered by you chaps,” he wrote. “We old Antarcticians feel very ashamed that we did so little, but to tell the truth in the three weeks it took to drag a sledge in that awful wet snow to Granite Harbour, we were just too exhausted at the end of the day to do work we knew we should!” Not counting side trips, we had reached Granite Harbour in five days behind our cheerful toilers!

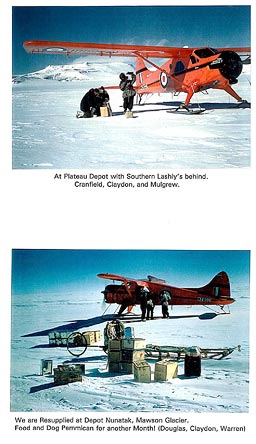

At Granite Harbour, sheer granite cliffs rise several thousand feet above the sea-ice and the MacKay Glacier-Tongue and we spent days up a new glacier we called the Benson, after Professor Benson. On the 24th, Claydon came in with Ted Gawn and a shiny new radio which had been built especially for us by DSIR to a design suggested during the winter by Mulgrew and Gawn. Peter had been very insistent that a better radio could be built than any available, and in fact sets of the new design were used by all field parties both New Zealand and American for the next ten years. We had tried all the currently available field radios and they were all hopeless. Unfortunately, the morse key was left behind, without which it could not work which meant another flight by Bill and Wally on the 26th, after Douglas had rattled out a message to this effect by means of a screwdriver!

At Cape Archer there were already 130 seals, half with pups, and another 96 at Cape Ross. Though the new radio could only transmit on CW (morse key) we could receive on RT (voice) and Ted Gawn kept us in touch with the activities of the other parties and by the 27th Sir E and the tractors were already in the upper Skelton preceded by Marsh, Miller, Canyon and Ayres with dogs, but the Crossing Party, it seemed, had not yet left their Base at Shackleton!

At Cape Archer there were already 130 seals, half with pups, and another 96 at Cape Ross. Though the new radio could only transmit on CW (morse key) we could receive on RT (voice) and Ted Gawn kept us in touch with the activities of the other parties and by the 27th Sir E and the tractors were already in the upper Skelton preceded by Marsh, Miller, Canyon and Ayres with dogs, but the Crossing Party, it seemed, had not yet left their Base at Shackleton!

Time was passing and there was much land to cover. Guy left with Richard to go inland to map the Fry Glacier and Douglas and I went up the coast, reaching the mighty Mawson Glacier in only two days. Where to camp in between was a problem, but the Lord Provides! Two stranded flattop bergs and a tilted berg in a triangle not only gave shelter but fresh ice without salt! The Mawson sends a great tongue out to sea, and we passed into a bay on its south side to find an easy ramp up onto the Piedmont which still extended this far north and sidled around west, camping in the afternoon under a high black range.

The next day we climbed Mt Gauss at the northern end of the range and overlooking the Mawson, though the snow at the top was at a 55 deg angle, but Douglas, though a large man was competent on the hill, though perhaps not exuding the confidence of an Ayres, Bowie or Graham. The Mawson must have been ten miles wide in the lower valley but had an immensely wide source at the plateau edge, ice spilling in over a width of more than fifty miles. A few nunataks showed through far to the west some of which a month later we visited.

The lower glacier had enormous tilted blocks over a hundred feet high and gaping crevasses, but incredibly, John Ricker, Hewson, Skinner and others three years later took dog sledges across it, though not without adventures. After two hours rest in the tent, we made a fast run back down to the sea in two hours and on to the Tilted Berg in another three, camping at midnight! We linked up with the other two at Gregory Island and pushed on on sticky salty snow and were back at Cape Roberts south of Granite Harbour on the 2nd November. Somewhat south of us, a small mountain glacier called the Debenham joined the Piedmont, and from the air it had seemed to be linked to the Mackay (which flows into Granite Harbour), and by taking a detour via the Debenham and the Miller we hoped to bypass the icefalls which had stopped Taylor, Debenham, Forde and Gran going inland any further than Mt. Suess, a sharp peak sticking up out of the ice about 5 miles inland.

The lower glacier had enormous tilted blocks over a hundred feet high and gaping crevasses, but incredibly, John Ricker, Hewson, Skinner and others three years later took dog sledges across it, though not without adventures. After two hours rest in the tent, we made a fast run back down to the sea in two hours and on to the Tilted Berg in another three, camping at midnight! We linked up with the other two at Gregory Island and pushed on on sticky salty snow and were back at Cape Roberts south of Granite Harbour on the 2nd November. Somewhat south of us, a small mountain glacier called the Debenham joined the Piedmont, and from the air it had seemed to be linked to the Mackay (which flows into Granite Harbour), and by taking a detour via the Debenham and the Miller we hoped to bypass the icefalls which had stopped Taylor, Debenham, Forde and Gran going inland any further than Mt. Suess, a sharp peak sticking up out of the ice about 5 miles inland.

We relayed loads up the steep Piedmont and made a dump over on the edge of the Debenham. When the time came to move over into the centre of the Debenham, though there few crevasses it was a maze of thaw tables and looked appallingly rough.

“Don’t you think we should stop and do a recce?” I suggested but Richard would have none of it.

“Oh, I think we’ll find a way. Come on, dogs, huit! Huit! now” and on we went. Somehow the problems melted away and soon we had a route up onto level ice a few miles west. Brookes and Warren went off south to look at the entrance to Victoria Valley up some very rough going which they called “Purgatory Glacier” and their station “Purgatory Peak” because they had so many sledge capsizes. Douglas and I had easy going on a quite flat surface but there was a band of rough thawed ice, probably caused by wind-blown dust extending diagonally over the width of the valley, but which could be passed by right against a bluff on the south side. Then it was only a rattle over flat ice to a magnificent red granite bluff on the north bank where our way was blocked by another belt of ablation pits apparently caused by more wind-blown dust.

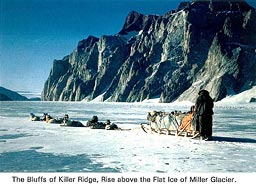

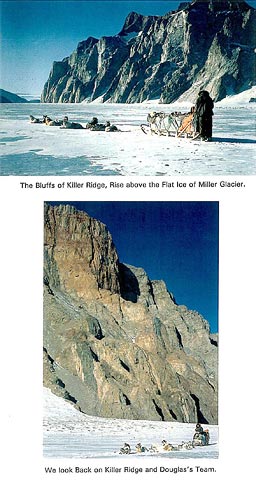

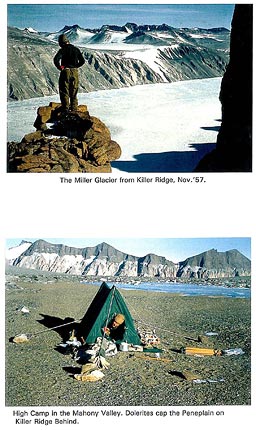

When Brookes and Co caught up a day or two later following our trail, Richard and I had a great old climb, granite being lovely coarse-grained stuff on which rubber boots never slip. The Miller formed almost a canyon with vertical cliffs rising about 3000 feet on the east, with the red granite bluffs capped by a five-hundred foot layer of chocolate-coloured dolerite, but with easier slopes barred with dolerite sill on the west.

When Brookes and Co caught up a day or two later following our trail, Richard and I had a great old climb, granite being lovely coarse-grained stuff on which rubber boots never slip. The Miller formed almost a canyon with vertical cliffs rising about 3000 feet on the east, with the red granite bluffs capped by a five-hundred foot layer of chocolate-coloured dolerite, but with easier slopes barred with dolerite sill on the west.

A little ferrying amid glacier tables ten feet high got us through but a handle-bar clipped some overhanging ice and a machine screw broke. It was repaired with light lash-line, the only repair needed in 1300 miles. We had to carry the sledges and loads for a chain or two over rock and soon we were away again, on glare-ice, but so flat it made no difference. How a now-stagnant glacier could have carved out such a trench I have never worked out. Again we back-packed a light tent up out of the Miller into a hanging valley to the west to do a station on Mt Mahony which overlooked the north arm of the Victoria Valley. The hanging valley was completely snow free and Richard looked about in appreciation.

“Now if this was Greenland, there would be a few musk-ox about!”

In the moraines below Mt Suess, Taylor and Debenham had found fragments of Devonian fish, and half way up the peak above the granite and below a dolerite sill fragment was a triangular wedge of sandstone.

“Aha!” said we. “So that’s where the Devonian fish came from!” We walked miles around that wretched island mountain and found piles of fish fins and other skeletal bits in moraine boulders, and next day climbed the steep rock and crawled over the wedge of Beacon which is what the sandstone is called, without finding them in place.

A fossil lying in a glacial erratic might have come from anywhere, though the rock was undoubtedly Beacon Sandstone but we had to find in place! At Mount Suess however, we could look at the eroded flat surface which had been worn down across the granites 400 million years ago before the Beacon sands were washed down onto it. This erosion surface is the one of the greatest known, it extends for more than a thousand miles, an almost completely level peneplain cut across granite and schist and I named it the Kukri Peneplain, as Ferrar had seen it first in the Kukri Hills, fifty-five years before. Nowadays of course it is called something else, but it is still there, a few little wave cut runnels showing where the sea first washed across it long, long ago! When we finally did find those armoured trout in place they were in sandstone alright but about 4000 feet above the Kukri Peneplain. How 4000 feet of sand could have accumulated over an area of thousands of miles in only a few million years I do not know.

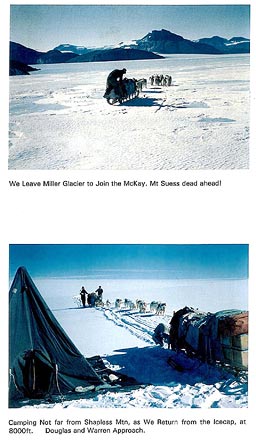

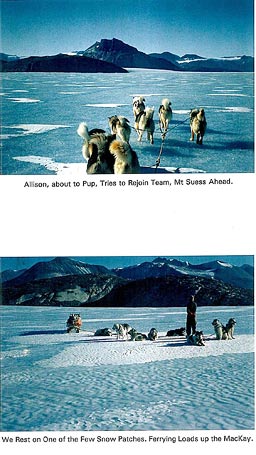

A great stagnant pond of ice lies where the Miller joins the MacKay and we rattled over its blue surface, pocked with snow patches. Alison, our dark, staid maternal bitch was expecting so we let her run free, but she dropped into her usual place in the team alongside her daughter, Zaza.

The MacKay was also icy in the lower reaches and we had to relay, dogs digging in claws, sleds grinding. We left a depot at the first snow, and had the usual wild ride back down the long rippled ice-slopes, rope brakes under the runners, jumping off and on, trying to keep our feet and keep the sled upright! From then on it was good snow and easy slopes but the Glacier was so wide and the

centre rather broken that we never did cross to the northern side where Mount Gran rose to about 8000 feet.

One day we returned to camp to find Alison off the span, our tent door gnawed through, and Alison curled up in Warren’s sleeping bag with a litter of pups! Fortunately all but one died as carrying a new litter would have been a little difficult! There was something of an icefall near the head of the Mackay but after a dog or two had fallen in crevasses, Guy and I prospected ahead to find a route with a 4ft crevasse only 20 yards on either hand but which our dogs and drivers took in their stride. We headed diagonally north across several small slots found in turn by Dismal, Bowers and finally Richard himself! I ran ahead with ice-axe, or on ski for several miles and we gained the edge of the plateau without so much as putting a toe in one! This was the fifth crossing of the Victoria mountains after the Ferrar-Taylor, the Beardmore, the…, the Axel Heiburg, and now the Miller-MacKay.

One day we returned to camp to find Alison off the span, our tent door gnawed through, and Alison curled up in Warren’s sleeping bag with a litter of pups! Fortunately all but one died as carrying a new litter would have been a little difficult! There was something of an icefall near the head of the Mackay but after a dog or two had fallen in crevasses, Guy and I prospected ahead to find a route with a 4ft crevasse only 20 yards on either hand but which our dogs and drivers took in their stride. We headed diagonally north across several small slots found in turn by Dismal, Bowers and finally Richard himself! I ran ahead with ice-axe, or on ski for several miles and we gained the edge of the plateau without so much as putting a toe in one! This was the fifth crossing of the Victoria mountains after the Ferrar-Taylor, the Beardmore, the…, the Axel Heiburg, and now the Miller-MacKay.

By the 27th we were well out on the Plateau amid sastrugi and camped on a possible landing strip a few miles north of a sharp isolated peak we called Plateau Nunatak (now ca!led Carapace Nunatak) Though standing only a few hundred feet above the snow, it was in fact about 7000 ft in elevation and higher than all but Tent Peak, the top of which was still visible to the east. Plateau Nunatak was intriguingly different, being a mixture of sandstone, basaltic pillow lava, and volcanic conglomerate with masses of zeolite minerals with some of the crystals of mesolite being as long as a finger, with some beautiful milky agates in the core of the pillows.

In the old muds were fossils of ferns and a little freshwater bivalve, which later showed this rock to be Jurassic in age, or about 160,000,000 years. This doubled the span of time previously thought to be covered by the Beacon Sandstone, so that sands were being more or less continuously laid down for 240 million years or so. Well, we thought, nice to find something really new!

Richard did his usual survey station on top, he and Douglas cutting steps part way up steep ice. I wandered up after them and Richard was quite upset, it was only later that I found Captain Hans Jensen had been killed on a similar nunatak in Greenland, and a few years later Warren came back by plane and fell on the ice at this same nunatak and broke a leg on the first day! So perhaps Richard had reason to be put out.

On Dec. 1st, Cranfield brought the Beaver in with our resupply, two months had gone by, we had done about 700 miles and we were right on that schedule so briefly put together by Sir E six months before.

On Dec. 1st, Cranfield brought the Beaver in with our resupply, two months had gone by, we had done about 700 miles and we were right on that schedule so briefly put together by Sir E six months before.

“Bernie! bellowed Bill; against the clatter of the Wasp motor, “Would you like a bit of a flight to look at the country north?” Would we ever, not the least because it was the only flight I personally ever had for what might be called scientific purposes in two years excepting the original Dry Valley flight. We banged and bucketed over sastrugi, engine screaming its usual banshee note and flew north over the wide Upper Mawson, there was in fact little to see except a group of odd turreted nunataks I called Hatters Castle, now called heaven knows what, and a few patches of crevasses. As we came back, there a few miles north of our camp was a horseshoe ring of rock, (later called the Allan Hills) virtually invisible from the south, but snow-free on the open, northern end. The rocks seemed to be flat-lying

Beacon Sandstone, but marked with wide, dark-greyish black bands, not rusty-red like dolerite sills, but more like coal! Both Scott and Shackleton’s parties had picked up lumps of coal in moraines but it had never been found in place, had we just seen a coal mine?

A second load came in next day flown by Claydon but John had his own ideas as to where we were and we finally heard and then saw him circling about fifteen miles south, out of range of our little UHF emitter. Douglas managed to contact Gawn at Base on CW,

“For God’s Sake! Tell Claydon to turn and fly north ten miles!” When John landed he was puzzled,

“I thought you chaps were in the head of the Mackay, not the Fry!”

“This is the MacKay, John!” we said with some sarcasm, (though, strictly speaking, we were at the watershed with the Mawson). There were letters and news of the others. The Americans had had another crash of a helicopter and a Dakota, making five aircraft lost in two weeks. Sir E was at Depot 700, 700 miles from Base and had permission from Admiral Dufek to go onto the Pole, with a promise to fly the tractor party out when they arrived.

“Seven hundred miles?” we thought. “Why, that’s about as far as we have done, not bad for tractors!”

Months before, I had thought I had found a loophole in the Great Plan.

“Look, Ed,” said I, with great cunning. “What happens if we reach the Plateau, and the plane crashes and we don’t get resupplied?”

“You will still have more than a week’s supplies, right ?“ said Sir E patiently.

“That means you can either sledge straight down to Plateau Depot which will be stocked, or back down to the coast and live on seal, whichever you prefer!”

“That means you can either sledge straight down to Plateau Depot which will be stocked, or back down to the coast and live on seal, whichever you prefer!”

Had we been operating in those halcyon days before the aeroplane and tractor, we could have surveyed exactly the same area but the other four doggoes would have had to put in the entire summer supporting us, first taking a depot up the coast, then one to Skelton Depot, then to Plateau Depot, and finally sledging up the Plateau edge to meet us. But without the aeroplane we would not have known about Skelton Glacier, or the Mackay, so it would have had to have been a three year expedition, but perhaps a more challenging one.

Richard and Murray Douglas took off for Tent Peak and Warren and I took Fido and Co and headed north to look for coal mines. We spanned the dogs near the first outcrop of volcanic cobbles in an odd yellow matrix and trotted down-wind for miles until we reached the bay seen from the plane in the middle of the horseshoe, and lo and behold, coal it was. There were four main seams up to ten feet thick, nice black, rather dirty coal, packed full of ferns and leaves of a plant called Glossopteris, which means it was Upper Permian in age, or about 200 million years. Lying on a partly eroded surface was a fossil log, about 15 inches thick, with about three growth-rings per inch and we picked at it curiously. It looked like a modern conifer, and it seemed that the earth was inclined enough to result in marked seasons even then. Actually, the Permian Magnetic Pole was in South Africa and presumably the spin pole was not far off, so this area was at a quite modest latitude at the time.

Richard and Murray Douglas took off for Tent Peak and Warren and I took Fido and Co and headed north to look for coal mines. We spanned the dogs near the first outcrop of volcanic cobbles in an odd yellow matrix and trotted down-wind for miles until we reached the bay seen from the plane in the middle of the horseshoe, and lo and behold, coal it was. There were four main seams up to ten feet thick, nice black, rather dirty coal, packed full of ferns and leaves of a plant called Glossopteris, which means it was Upper Permian in age, or about 200 million years. Lying on a partly eroded surface was a fossil log, about 15 inches thick, with about three growth-rings per inch and we picked at it curiously. It looked like a modern conifer, and it seemed that the earth was inclined enough to result in marked seasons even then. Actually, the Permian Magnetic Pole was in South Africa and presumably the spin pole was not far off, so this area was at a quite modest latitude at the time.

We collected bags of sample and set off home, against the katabatic wind flowing from the Plateau down the Mawson, a steady grind uphill for 1600ft of four and a half hours, so we camped where we left the dogs. The glaciated rock surface which only just lay clear above the ice was covered in lines of windrowed stones.

On the ice were rusted black lumps, rather like dolerite and I idly wondered how such heavy fragments could be there as they were too heavy for wind to move. However, one of the most frustrating things about the accounts by Scott and Shackleton’s parties was that most of their rocks were erratics from heaven knows where and we had firmly resolved never to pick one up! Years later someone did and found one of the world’s greatest concentrations of meteorites, stonies and nickel-irons, fallen on the ice and concentrated in a kind of glacial backwater! So fame passed us by again!

It seemed we should report the coal find back to Base, after all, we were supposed to be a scientific expedition and a lot of people had put up money to support us, so we should show we were doing at least something. Guyon disagreed, quite strongly, this was mere publicity hunting, an aspect that hadn’t occurred to me, but it seemed to me that even the Ross Sea Committee might welcome some news to indicate we were not just playing the fool, so the message went out but relationships with Guy were cool for a time. He was quite outraged later to find it even got into newspapers! As we lay in our bags having a well-earned rest, there were sounds of a dog off.

It seemed we should report the coal find back to Base, after all, we were supposed to be a scientific expedition and a lot of people had put up money to support us, so we should show we were doing at least something. Guyon disagreed, quite strongly, this was mere publicity hunting, an aspect that hadn’t occurred to me, but it seemed to me that even the Ross Sea Committee might welcome some news to indicate we were not just playing the fool, so the message went out but relationships with Guy were cool for a time. He was quite outraged later to find it even got into newspapers! As we lay in our bags having a well-earned rest, there were sounds of a dog off.

“Hark, do you hear the patter of tiny feet?”

“More like the pounding of bloody great hoofs!” came the weary reply. We rode on the sledge on the run back to Plateau Nunatak and made a spectacular dash up to the tent of the others who had arrived back shortly before. Richard was out, smiling broadly, camera in hand, to welcome back with open arms, not us of course, but his beloved boys.

“There’s me boy, how are you lad, did you behave?” and more stuff better suited to a suburban pensioner and a pet brace of spaniels! Of course one can’t brag how well they pulled and handled, every driver having a pathetic wish to believe that his dogs would never work for any other man! Once in the winter I took George Marsh’s team out for a run on the Barrier and on return spent half an hour assuring a distraught George, that no, they hadn’t pulled well, yes, I had great difficulty getting Hemp to obey commands, (none of which was true) but George finally relaxed and smiled complacently!

Hatter’s Castle proved to be more lavas and pillows with zeolites and we went down the Mawson towards what I called Madman’s Island, it having a Hill, a Peak and a Mound (for those who have read Ion ldriess). On a difficult icy descent we actually let the dogs off and manhandled the sledges down. We moved south-east and climbed a couple of thousand feet onto a peak we called “Monument” which overlooked the Fry Glacier. It was a good survey point even if the geology was of little but dolerite. The last 200 feet were steep and though Richard and Douglas had cramponed up I thought of the descent and cut steps.

Sledging back up the Mawson, a Globemaster passed overhead going north-west. Richard gave it a foul look and pressed on. Half an hour later another plane appeared. Richard stopped the dogs and swore.

“Gets more like Brighton on a Bank Holiday every day!” he complained (we were about 67 days out!). Back at Madman’s Island we could see in the far distance the Thule Nunataks and here we had one of those urges to go on, and on, and on, and never back. We had about five days food left and the Thule Nunataks (now, I think, called “Outpost Nunataks”) looked about forty miles away, two days easy and a day there, no problem to such as us.

Richard laid out a base line and took angles and pursed lips, they were seventy miles away.

Richard laid out a base line and took angles and pursed lips, they were seventy miles away.

“OK,” said I, “Half rations it is.” What settled it was discovering that Guy and I who were sharing tents at the time, were low on kero and Richard read us a lecture on how serious this was. Later an odd bonging sound was heard in our fuel can, which proved to be due to kerosene leaking through a rust hole due to the salt water in the hold of the “Endeavour” two years before and we had only two days fuel left! We gave up ambitions to reach Thule Nunataks and pressed on back to Plateau Nunatak, face in to the south-west wind, with a visibility of fifty yards in the drift, but the sun was flickering through it so navigating was no problem and we pressed on dourly straight into the wind and camped a little beyond our nunatak on the level Plateau on the 14th Dec.

“What would you do?” I asked Richard, “Under circumstances like that, barely able to get home, and someone breaks a leg?”

“Leave him,” said Richard briefly, “My job is to get the most men home I can, not risk a whole party for one man.”

I thought about this, it didn’t seem quite right somehow.

“No!” said I.

“No!” said I.

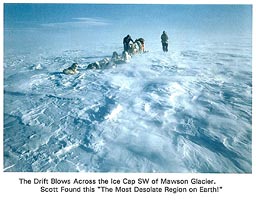

“Suit yourself,” and in so few words an understanding was reached. We rearranged gear, sledges were dragged into tents and lashings and white-whale bindings tightened, the joints in the flexible Nansens were beginning to crack. We had had new underwear sent out and walked off down wind to do a clothing change. I changed mukluks, throwing out the worn pair (which were found by Hugh Logan twenty-five years later). We left with loads of 1100lbs, the rest being left in a small depot, intending to head south parallel to the edge of the mountains to the east, but being forced by the sastrugi to travel for three days direct south-west. We were over 9000 feet altitude and the heart pounded if we ran. We then came to the end of the wind-chiselled sastrugi, some of which looked like inverted canoes or as Scott said in 1902 “like barbed fish-hooks”. The sky was always blue above the intermittent drift and apart from concern that we were being forced so far out onto the Inland Ice I think we enjoyed the remoteness and the sparkling purity, yet Scott, only a few miles away had found it depressing that:

“..beyond the horizon are hundreds or even thousands of miles which can offer no change to the weary eye ... and one knows there is neither tree nor shrub nor any living thing nor even inanimate rock - nothing but this terrible limitless expanse of snow. It has been so for countless years and will be so for countless more we have been discussing at supper whether future explorers will travel further over this inhospitable country. Evans remarked that if they do they “would have to leg it!”

I could wish Evans could have seen us as we turned back east, on smooth snow again, dogs scampering along to the cries of the drivers, “Come on boys, huit now, up lads, come on boys!” as we slid effortlessly again on ski.

Finally a mountain top came into view and we pressed on over the newly fallen snow which thickened until it was six inches deep and Richard went ahead on ski to break trail. More mountains came into view, the Lashlys, Mt Feather, Lister, Knobhead and Terracotta, we were in sight of familiar ground and we camped only a mile or two from rocks at the western foot of Shapeless, the temperature being so warm that we were not wearing anoraks, at at least 8000 feet altitude.

Finally a mountain top came into view and we pressed on over the newly fallen snow which thickened until it was six inches deep and Richard went ahead on ski to break trail. More mountains came into view, the Lashlys, Mt Feather, Lister, Knobhead and Terracotta, we were in sight of familiar ground and we camped only a mile or two from rocks at the western foot of Shapeless, the temperature being so warm that we were not wearing anoraks, at at least 8000 feet altitude.

Mackenzie, a reporter, asked over the radio what we intended to have for Christmas dinner and we sent a reply;

“Owing to heavy loads have thrown away medicinal brandy, extra feed for dogs, work as usual!” In fact someone produced Christmas cake and we ate a cube each with lemon tea! Ted Gawn enquired what we would like for Christmas, and Douglas tapped out;

“G wants television set to look at Sally (his fiancee), B wants a miners lamp, R a jet pack and the silly B- that made this up don’t deserve nothing!”

The radio gives an opportunity for some lightening humour. A few years later, James Wilson and I were camped not thirty miles from this spot and we listened on the radio to the predicament of a party north of Terra Nova Bay who were waiting resupply by air and were nearly out of food. The weather stayed bad and in the end they were down to no dog food and half-a-day’s manfood. One of the party was a friend, Maurice Sheehan, known by his school nickname as “Bogs”.

We sent them a helpful message;

“Suggest you either feed Bogs to the Dogs or a Dog to Bogs!” and were so overcome by our own wit we could barely move for days!

Even Gawn, that old misogynist wished us a Joyeux Noel. We put on skis and climbed Shapeless on Xmas Eve hoping for a fast ski-run down but the snow had turned to sand and one had to ski-walk down even steep slopes. On Christmas Day we ski-toured the West Peak and found more coal and more fossils and on Boxing Day we walked many miles down to the southern side of the Upper Wright Glacier around Horsehoe Mountain and what is now Mount Fleming finding Calamites plant-stems, and more coal and we ran down the soft, sandy crumbling slope of Fleming with thin coal and plant lenses every few yards. It is now one of the most famous plant-fossil localities and is Triassic in age at the top, ie, between the age of the Coal seams at the Allen Hills in the Mawson, and the Jurassic of Plateau Nunatak. It seemed a little unreal to sit with a great slab of impressions of what were undoubtedly tropical ferns and trees amid surroundings too frigid for even the lowest forms of life, just as it has been for ten million years or so. Another gap filled in.

Even Gawn, that old misogynist wished us a Joyeux Noel. We put on skis and climbed Shapeless on Xmas Eve hoping for a fast ski-run down but the snow had turned to sand and one had to ski-walk down even steep slopes. On Christmas Day we ski-toured the West Peak and found more coal and more fossils and on Boxing Day we walked many miles down to the southern side of the Upper Wright Glacier around Horsehoe Mountain and what is now Mount Fleming finding Calamites plant-stems, and more coal and we ran down the soft, sandy crumbling slope of Fleming with thin coal and plant lenses every few yards. It is now one of the most famous plant-fossil localities and is Triassic in age at the top, ie, between the age of the Coal seams at the Allen Hills in the Mawson, and the Jurassic of Plateau Nunatak. It seemed a little unreal to sit with a great slab of impressions of what were undoubtedly tropical ferns and trees amid surroundings too frigid for even the lowest forms of life, just as it has been for ten million years or so. Another gap filled in.

Years later I attended a Mid-winter’s Eve party for Old Antarcticans in the City of Gore invited by one, Bogs Sheehan and I met a young woman who claimed to be a palaeobotanist, that is, she worked on plant fossils.

“Really, m’dear?” I said, “ How interestin’! You know, we found this facinatin’ place on the edge of the Plateau above the Wright Valley, plant fossils all over the place, only eighty days out of Base, you really should try to get some from there, y’know!”

“Oh, you mean Mount Fleming!” she replied. “I’ve been working there for the last two years, we stay at Vanda Station and helicopter up there every day!” Complete collapse of Ancient Explorer!

©2007 - may not be reproduced without permission