16 – The Spring Journeys

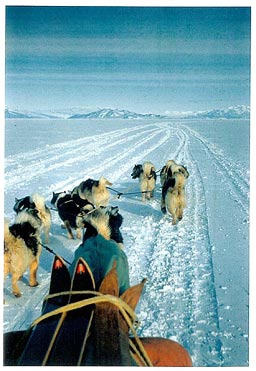

Winter, as might have been gathered, was scarcely a time of hibernation though we could not venture far. With the month divided into a two-week period of moonlight (if the weather was clear) and two weeks of only starlight we had to confine our odd runs with the dogs to moonlit days, the Aurora being a feeble and a pallid thing compared to the roaring displays of rotating red, yellow and green searchlights that one sees in south Otago or Sutherland, (Southland, you Sassenach!). Running beside the sledge across the airfield with the moon hidden by the hills one could not see the snow underfoot, but coming out from behind Observation Hill into the full blast of the moonlight (so to speak) one could almost feel the warmth on one’s face, though a thermometer, being unswayed by psychological reasoning still maintained it was forty below! Even the mountains of the distant Royal Society Range glowed in the light of the moon.

Winter, as might have been gathered, was scarcely a time of hibernation though we could not venture far. With the month divided into a two-week period of moonlight (if the weather was clear) and two weeks of only starlight we had to confine our odd runs with the dogs to moonlit days, the Aurora being a feeble and a pallid thing compared to the roaring displays of rotating red, yellow and green searchlights that one sees in south Otago or Sutherland, (Southland, you Sassenach!). Running beside the sledge across the airfield with the moon hidden by the hills one could not see the snow underfoot, but coming out from behind Observation Hill into the full blast of the moonlight (so to speak) one could almost feel the warmth on one’s face, though a thermometer, being unswayed by psychological reasoning still maintained it was forty below! Even the mountains of the distant Royal Society Range glowed in the light of the moon.

From the 12th to 17th June we had a right royal blizzard with wind up to 70 knots sweeping such a wall of snow that from the galley, a light in the next hut a few yards away could not be seen. Snow blew in through fine cracks round the windows of A Hut which we caulked with string! The roof of C hut began to lift and snow to pour in and Sir E, Ellis and Bates roped up as for a major mountain climb and vanished into the dark, and heavy blows on the roof were to be heard as the wire ties were tensioned.

Conversation was difficult to impossible in the roar, but work went on, I filled in time sewing tents, bosticking on patches, cutting rock sections, and developing films. In the lulls we discussed the Theory of Relativity for which Bates as usual could produce good reasons for doubting Einstein, Whether Genius can still be Demonstrated due to Complexities of Modern Life and, Whether the Human Brain has Reached its Limit of Development, all heavy stuff. I have never had conversations like these underneath tropic palms so perhaps climate has a great deal to do with the development of Thought!

On the 18th June the wind died and we immediately turned-to, to rescue the dogs who were nearly buried in the deposited drift and dug out about twenty frozen and buried seals, our supply of winter dog-tucker! After dinner that night, Richard entertained us with tales of the Greenland fur trappers and of his work near Danmarkshavn. He did not mention and I did not know until reading of it, that his partner, Capt. Hans Jensen was killed in a fall in the middle of this work.

Down at the airfield we looked for the aeroplanes by the glim of hurricane lanterns. The Beaver had been put away in its crate for the winter up on the rock above the tide crack, but the Ops Huts had only their rooves showing and the Auster had totally vanished until we stumbled over something projecting a few inches which proved to be the tip of the propeller! Days with the shovel were lightened when the ever-enlightened Wally Tan attached a grader blade to a tractor and graded out ramps up which the plane and huts could be dragged! The planes were in a bay below ice-cliffs for protection against wind, but axiomatically this means drift will be deposited, in this case at least eight feet of it.

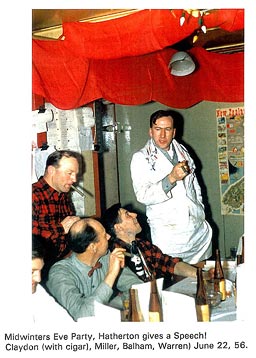

Midwinter’s Eve on the 22nd of June is always the occasion for great festivity and we had a very formal Dinner with George Marsh attired in Dinner Jacket and Black Tie. Almost everyone shaved for the event, an action I at least bitterly regretted as one gets a frostbitten face quite easily when minus the protective whiskers. Speeches were given, stories told, strathspeys were danced and the port passed. Intellectually one may know that if winter has passed and sun returned at least four billion times in the past, there is a good chance it will do so at least one more time, but one can never be quite sure! Bob Miller and Roy Canyon calculated the exact minute of the turnaround of the sun and came through the sleeping huts (it was about 3am), singing carols, bless the dear lads!

Midwinter’s Eve on the 22nd of June is always the occasion for great festivity and we had a very formal Dinner with George Marsh attired in Dinner Jacket and Black Tie. Almost everyone shaved for the event, an action I at least bitterly regretted as one gets a frostbitten face quite easily when minus the protective whiskers. Speeches were given, stories told, strathspeys were danced and the port passed. Intellectually one may know that if winter has passed and sun returned at least four billion times in the past, there is a good chance it will do so at least one more time, but one can never be quite sure! Bob Miller and Roy Canyon calculated the exact minute of the turnaround of the sun and came through the sleeping huts (it was about 3am), singing carols, bless the dear lads!

I believe this was the night that we had one of our radio links with the Crossing Party wintering on the other side, and we had a pep-talk from Bunny Fuchs which Ted Gawn put onto a speaker out in the Mess. People who knew Bunny said he was rather humourless, but his speech (for such it was) exceeded all. He began by congratulating us on all that had been accomplished, the rapid build up of the base, the exploration that we had managed, but intimated that this was not enough. In what can only be described as hectoring tones delivered in a pedantic very upper-class accent he went on.

“From now on our efforts must be redoubled! We must strive night and day, I expect you to work at least twelve hours a day, and we can take no more holidays lounging in idleness, all must be sacrificed to the great effort!” and his voice rose in pitch.

The man’s off his trolley!” whispered someone and even Sir Ed looked appalled.

“There’s something funny about this!” said Guyon to me in a low tone. “where has Marsh got to?” and he sprang up and threw open the door to the radio shack and there was a guilty George Marsh with a microphone in his hand and a grinning Ted Gawn behind.

“Got you all didn’t I?” chuckled George. And he really had.

When the ionosphere allowed it we could make telephone calls home. Once Tania and I were exchanging experience with Sir Charles and Lady Wright, and she had an interesting comment to make.

“You know my dear,” Lady Wright said turning to Tania, “At least you could occasionally talk to your husband and know he was well. In our day we did not know for three years whether they were alive or not and for poor Lady Scott and Mrs Wilson when the expedition finally reached New Zealand, their men were long dead!”

At times, the conversations with home did not cheer one greatly. Once after we had endured a week of blizzard Tania called to relate how much she was enjoying her house surgeon stint at Rotorua.

“Last Saturday,” she said, “We all went over to Mokoia by boat and had a barbecue, and we sat in hot pool and then cooled off in the lake and the Maori nurses played their guitars. Lovely. You should have been with us!” I should indeed!

Guy Warren was engaged to a girl called Sally who one evening with bad reception was telling him of furniture she had bought for their house. “And then there were these lovely diamond squares!” she said, “I know it was naughty of me but I couldn’t resist …..!!!&&$#@"

“What? What?” shouted Guy, but the static was too severe. For a week he went round muttering “What has that woman done?” and finally we got through to NZ again. Sally had bought a set of “Dining room chairs!”

All the same, without our occasional contact with home, the isolation would have been severe.

There were a number of disasters at Hut Point over the winter, their garage caught fire and burnt their only usable D8 tractor but Bates was able to help get another one operating. Their elderly Chief Engineer had great faith in Bates, he remembered when Americans were the same, able to fabricate anything out of scrap steel, instead as they were now, only able to replace factory units. On the 12th July, they had a helicopter crash when flying in the dark with an unset altimeter. Cole, a mechanic was killed, the pilots, Lts. McNeil and George Pullen were not badly hurt, Captain Anderson had leapt out of the burning wreck, and, realising Bernie Fredovich, a meteorologist, had not got out, dived back into the flames, and released Fredovich’s straps and pulled him forth. I believe it was Pullen who rolled them on the snow to put out the burning clothing. Chuck Novosad, their young doctor, was distraught and George Marsh moved over to Hut Point to help out. A few days later I went over to see Fredovich whom I knew well, and Chuck was almost in tears.

“I don’t know whether I could have handled this if it hadn’t been for George!” he repeated. “George has been just fantastic!” Now George was many things but care for the human race was not high on his priorities, so I went to him, as he scuffed round the tiny “Ward” in mukluks.

“I don’t know whether I could have handled this if it hadn’t been for George!” he repeated. “George has been just fantastic!” Now George was many things but care for the human race was not high on his priorities, so I went to him, as he scuffed round the tiny “Ward” in mukluks.

“What have you been doing, George?”

“Very little except hold hands,” George admitted. “Chuck was in a panic with no support, should he attempt plastic surgery, what should he do? All I said was; “Not to be thought of, m’ dear chap. You have no sterile conditions, no trained plastic surgery staff, not to be thought of, nurse them through it and the surgery will be done back in the States.” Now he’s accepted it!” In an emergency, George’s flippancy vanished and he could be definite and incisive, and moreover, right, and I could believe Novosad found his presence a great support.

Every day, Ted Gawn took an hour’s class in the sending and receiving of morse, because, using CW we could transmit to the other side of the continent, but to this day, voice transmission is not reliable, thanks to the disturbed state of the ionosphere. At one point I gave a talk on geology and what kind of samples to collect, emphasising that any samples taken must be of nice fresh rock and knocked off in place. It must not have sunk in, as when the tractor party returned from Crozier they proudly brought great chunks of old pink granite which they said was the typical rock of the area. It was of course old moraine detritus carried by the ice at least four hundred miles, as the local rocks are all alkali basalt, not one of which had they collected. It began to seem that one could not rely too much on amateur efforts!

The only major break in the routine during the winter came when one was on duty as “House Mouse”, a term dreamed up by Roy Canyon for the unfortunate who was cook’s assistant and general dogsbody for the week. The “House Mouse” cleaned up the tables after meals, did the washing up, swept out the Mess, kept the ablution blocks clean etc. The one had to keep the water tanks full which meant taking a tractor out in the dark over onto the bayice and digging a ton or so of snow blocks. These had to be heaved through a small hatch in the side of the generator huts and the snow blocks dropped into the upper of two large galvanised steel tanks through which the exhausts of the diesel generators ran to melt the snow and heat the water. I remember once I overdid it and the lower water tank overflowed to the jeers and sarcastic comment of the base engineers.

Then on Sunday one had to cook to give Sel Bucknell a day off. My speciality was “Chicken Maryland” which meant boiling up half a dozen frozen chickens, breaking them up into chunks rolling them in crumbs etc and baking, a kind of “Kentucky Fried”. Then the poor “House Mouse” also had to keep the cook supplied with meat which meant going down into the ice grottoe in the tide crack near the airfield, (our Deep Freeze) and bring out the legs of lambs, sides of beef etc the cook wanted on the other six days.

Some people especially George Marsh, (with whom I shared a Sunday Dinner Effort with once) went to no end of trouble with the Sunday evening meal, baking pastries and exotic dishes. George began the day at about 5am by placing a bottle of wine within reach and as the day wore on the bottle lowered and the cries, exclamations, exhortations and profanity became louder and louder as George rushed about clad in mukluks, army pants, a not over clean singlet and a chef’s white hat! Sometimes we even typed up menus! However, “House Mouse” was a bit of a strain fielding complaints in all directions and it was always a relief when it was over and one could go back to feeding dogs and packing ration boxes.

I probably spent too much time over the winter in the garage overhauling the weasels and partly building the “Caboose” which was later towed to the Pole. However, once our tents and trail gear had been overhauled and the ration boxes packed, there was little we could do for our own summer excursions other than run the dogs whenever possible. Our trail rations had the virtue of being simple at least! Breakfast consisted of oatmeal porridge with powdered milk and sugar, followed by bacon and powdered egg. Lunch on the trail was a buttered, rather greasy biscuit and hot cocoa carried in a thermos, with a bar of chocolate. Dinner at night was a bar of pemmican melted into a sludge, with cooked potato powder, followed by a cup of tea. The calories seemed adequate as we lost no weight but after a few months one rather lost the desire to eat!

The dog food was one of our major triumphs. Scott of course, had rather disastrous experience with dogs rapidly dying as he fed them on what Nansen had recommended, dried stockfish. Now fish is almost fat-free and in a cold climate dogs need about a 50% fat diet and it was later found that mutton (quite adequate in New Zealand) is totally inadequate for dogs in the Antarctic. The experience of the Falklands Islands Survey with a pressed dog pemmican was that it was only partly successful, in fact Marsh once said that on an eight-hundred-mile or more journey, one must expect to lose perhaps a third of the dogs.

The dog food was one of our major triumphs. Scott of course, had rather disastrous experience with dogs rapidly dying as he fed them on what Nansen had recommended, dried stockfish. Now fish is almost fat-free and in a cold climate dogs need about a 50% fat diet and it was later found that mutton (quite adequate in New Zealand) is totally inadequate for dogs in the Antarctic. The experience of the Falklands Islands Survey with a pressed dog pemmican was that it was only partly successful, in fact Marsh once said that on an eight-hundred-mile or more journey, one must expect to lose perhaps a third of the dogs.

Byrd had arrived in New Zealand in 1938 with dogs dying aboard ship having been fed on a trial pemmican of compressed meat, fat and cereal. It was analyzed by the Home Science Department at Otago University who found it lacked several vitamins and it was rehashed by Cadbury-Fry-Hudsons with additives and was a complete success. Nearly twenty years afterwards Dr Muriel Bell of the Home Science School found on her predecessor’s desk the precious formula! Our dogs flourished on it, in fact at times we tried eating it ourselves, some swore it was vastly superior to the man-ration!

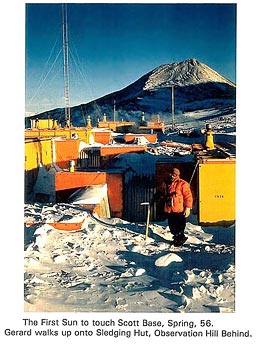

By August there was a distinct glow in the sky at midday with a twilight lasting several hours and on the 26th Brookes and I went out for a run on the Barrier. I measured up my snow accumulation stakes and found an average of 12 inches more snow and we carried on out a few more miles on a visit to Old Sol who would otherwise be hidden behind Erebus. At 1:15 pm a rim of apricot hue gleamed above the sastrugi somewhat to the east of Terror and we stood on the creaking snow as the air, at 50 below, crackled and we waited.

O, Rosy-fingered Dawn, Child of Morning! Was ever such a sight? The gleaming shafts lit the snows and then us and the sledge, and nine huskies lifted their voices and sang the Song of the North in unison. We warmed in the glow, the ice in our beards melted, or at least seemed as though it might, and then it was gone, but we were reassured, the sun was coming back, we would survive and life would go on!

Brookes and I had been reading and debating about the existence or otherwise of a “Snow Valley “ which Armitage, in 1901 had sketched in behind the Southern Foothills in front of the Royal Society Range, but the existence of which Scott’s 1911 parties had denied. Again, a major geographical problem and within sight of our front door! We determined to sledge over and have a look as a test run to the main Northern Journey which would take all summer.

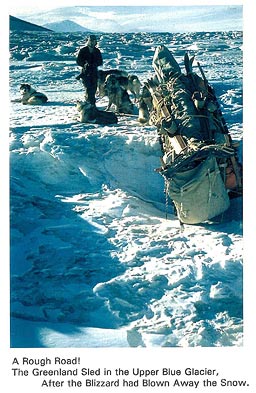

On Sept. 3rd we made a trial run with one of the heavy Greenland sleds whose runners are made on a single solid plank, the Blue Glacier being reported as extremely icy and rough and we did not want to risk our Nansens. We went out in the Sound and round to Glacier Tongue for about 25 miles and again for a few minutes silhouetted against the bergs, the frost smoke and the mirage, we waved “Hello” to old friend Sun, but by the 10th the sun was momentarily falling on the Base and familiarity was breeding if not contempt then acceptance that our world was changing.

On the 11th Sep. we got away at 9:30, heading west across the Sound and accompanied by Roy Canyon and Bob Miller with their teams. Miller, though over forty years of age, was something of a runner, and I would glance back at the other sleds with the drivers sliding along on skis, to see Miller bobbing along in a steady run, wearing no anorak, but his army jersey solid with frost, it being -27! We made 21 miles, camping beside the Dailey Islands. At the Stranded Moraines next day, we relayed a load of 250lbs up onto the Piedmont and then hurtled back down the toboggan run to the sea-ice for the night. Miller and Canyon left next morning for the New Harbour area and possibly Marble Point, and we sledged up and across the Piedmont, staying above the edge of the splintered and torn Blue Glacier. The snow was soft and we put on wide runners made from an old pair of skis which soon split, but we pressed on, often pushing and camped after eight miles near a

rock spur.

It was a very modest and scruffy little spur of the Northern Foothills, but it was the first continental rock we had set foot on in the last six months and I collected marble and schist samples almost lovingly. Suppose we had located the Base on the Mainland after all, would we have done fieldwork through the winter by the light of MacFarlane’s Lanthorn? (ie, the moon, to those who don’t know their own culture!) As it was we spent only five months of 16 actually on Antarctica.

It was a very modest and scruffy little spur of the Northern Foothills, but it was the first continental rock we had set foot on in the last six months and I collected marble and schist samples almost lovingly. Suppose we had located the Base on the Mainland after all, would we have done fieldwork through the winter by the light of MacFarlane’s Lanthorn? (ie, the moon, to those who don’t know their own culture!) As it was we spent only five months of 16 actually on Antarctica.

Striking camp at l0am we pushed on with hard eroded ice sloping left down to the glacier, alternating with snow hollows. We took turns running in front or pushing at handlebars and shouting to the dogs. After climbing a small icefall the going flattened and we made better time, Cranfield made a low pass in the Auster and we waved and then camped under a hill, now being past the Coast range (named The Northern Foothills by Scott) to where the neve area opened up and we could see the broad “Snow Valley” to the south-west, a triangular snow-catchment perhaps twenty miles long and broadening to a width of perhaps ten miles near us. Taylor, in 1911 would have had a foreshortened view from the Koettlitz Glacier, but the weather must have been bad for him to have thought that the stubby Miers and other valleys extended west right up to the main Royal Society Range. In any case, his scathing remarks about the standard of work done in the days of the “Discovery” were quite uncalled for! Our clothes were rigid with frost and we retired to the tent for a good dry-out.

The next day I climbed the ridge to the north finding solid rock studded with large green diopside crystals and other odd minerals such as scapolite. The overcast slowly crept down the face of Lister and I returned about 5 pm, Richard having set up his theodolite near the tent taking rounds of angles. On the 16th the weather improved and we set off towards Lister, crashing over pinnacles and glacier tables with a dusting of new snow. We ran into one pinnacle and broke a deck board, but I ran in front for a couple of miles finding the best route onto the neve snow which periodically subsided a foot or two with a loud “woof” to the alarm of all. The dogs were bad-tempered, each believing the others were not doing their share and tending to turn on each other.

At one point in the rough going a ski tip caught under a runner and I fell. Now Brookes had been dropping remarks about people who couldn’t keep up being left behind, and he carried on, I suspect with the intent of trying me out! It was impossible to catch up without poles on such a slippery surface and I pulled skis off arid started to run up the slope after the fast-disappearing sledge. Then a foot went down a crevasse so I firmly tucked both skis under an armpit, as areas of snow fifty yards across dropped with a “woof” leaving one a little breathless, not entirely from the exertion. With smooth-soled mukluks there was little chance of catching up, but after half a mile, Brooke stopped. As I panted up, he stepped out of his ski into a prepared stance obviously expecting to have to defend if not his honour, then certainly his person!

“Damned if I let him see I’m annoyed,” I thought, so I merely dropped my skis beside the sled and said “Shall we go?” A few months later we reminisced about the incident.

“I could see you were pretty mad!”, chuckled Richard, “In fact I thought you might have a go at me so I thought I had better be ready”.

“It did cross my mind,” said I. However when two men are even a hundred miles from Base, it is no time to be setting about your only companion, even if he has richly earned a clout ‘i the ear, you may be required to save his life a few minutes later, or he yours. In such strange ways do men get to know each other. All the same, there was a case on one Greenland expedition where two men decided to have it out and being fairly well matched, set about each other until they both dropped in the snow from exhaustion!

“It did cross my mind,” said I. However when two men are even a hundred miles from Base, it is no time to be setting about your only companion, even if he has richly earned a clout ‘i the ear, you may be required to save his life a few minutes later, or he yours. In such strange ways do men get to know each other. All the same, there was a case on one Greenland expedition where two men decided to have it out and being fairly well matched, set about each other until they both dropped in the snow from exhaustion!

Near the head of the “Snow Valley” we camped again and climbed a small black rock peak overlooking the Miers and Adams valleys whose glaciers once flowed into the Koettlitz. It was an evil little mountain of weathered gneiss moulded into goblin faces and black caverns interspersed with sliding screes of micaceous blocks. Though only thirty-below, it was a dull grey day and Brooke set off at too fast a pace for comfort and clothing got wet so the two hours on the summit taking angles can only be remembered as being the most raw and chill I have ever experienced. A series of stubby valleys extended from below us down to the Koettlitz Glacier, each one with a short, wall-sided glacier at its head, then a frozen meltwater stream extending down to a frozen lake lying in a wide, dry valley, the Miers, the Adams, the Marshall, the Garwood. Thirty years later I spent a few days in a warm hut by the Adams Burn and could stare up at our little mountain and dip clear sparkling water from the burn.

We headed on south-west towards a tributary from the main range but suddenly there was a shattering roar and the Auster leaped into view over a nearby nunatak and came straight at us at zero feet with the trailing end of the ski battering the surface. Cranfield, (who else?) obviously wanted to see us dive, and dive we did as he lifted just enough to clear the sledge and flashed on. Unfortunately he forgot his trailing aerial which struck the load though not us, in passing at about a hundred knots, followed by our cries of abuse! There was a rather more serious side to all this of course, whenever we asked for flight time to get a preliminary look at the country we were to sledge over we were always told, “There is not enough fuel” but there seemed to be unlimited amounts for mere joyrides. I don’t know whether the Auster has its aerobatic rating, but Cranfield now tells me that one day out with Vern Gerard, he put the Auster through a loop!

We dropped the load and went on up to a saddle with the Howchin Glacier for more angles and samples, and then ran down the glacier to find no good snow to camp on. Finally we had to camp on snow too hard to dig blocks from so we merely piled ration boxes on the tent skirt, probably the only time we did so in two years. Heavy black clouds built up to the south and in the night the wind rose and was soon gusting to sixty and then eighty knots. The canvas slatted madly and drift blasted in under the skirt, we were both fully dressed and hanging onto tent-poles for dear life.

“I’m just going outside!” shouted Richard.

“Don’t be “Some Time”!” I shouted back, as I felt myself being lifted into the air. Richard crawled out, dug a narrow trench to bury the edge of the skirts with his ice-axe, and on his knees, pushed the Greenland sled onto the windward skirt and lashed down everything.

“lt's the best we can do!” he said, crawling back through the madly slatting door. In the same blizzard, Harry Ayres was battling a tent with a broken pole at Cape Crozier. The wind died in the next afternoon and I walked over to a granite spur of what we called Corner Peak, south of Lister. From close up there seemed to be considerable differences with the existing maps. I tried to talk Richard into making an attempt on Lister, straight up its East Ridge, but, “Not on!” he said, shaking his head.

I did not argue strongly as it could have been minus fifty or sixty on the summit, but I thought we could at least have given it a try! Four years later I looked down the East Ridge and remembered our little camp and even though it was summer, contacted a little frostbite in the toes. The escarpment of the Royal Society Range rose six or seven thousand feet above us, cut by small and steep glaciers. The low snowfall of the region means it is much less glacierised than would be the case in a temperate zone.

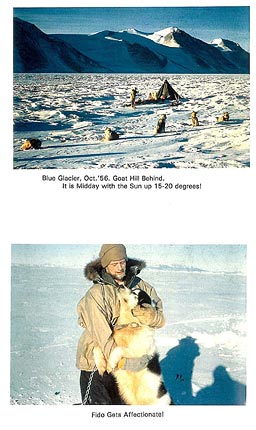

The gale left behind a different world, all the winter snow was gone leaving only the hard ice pinnacles, ablation pits and tables. We crashed on down the Snow Valley and the Blue Glacier, running alongside, pushing the sled around the worst dangers, periodically coming to a halt with a smash! We camped under Hill G3 on the south side and next day I climbed the hill, (now called Goat Hill). The next day was hectic indeed as the snow-hollows we crossed on the way up were now open crevasses and we broke through several and we fought to prevent the sledge overrunning the dogs and killing one.

“What will we do if we smash the sledge?” I panted at one stop, but Richard was unworried.

“Camp a few days, sew up carry-bags for the dogs and walk home!” was his casual solution. Finally luck smiled and we found a thaw channel, of what must be a major river in the height of summer, and its bed still contained a layer of snow. We careered down this toboggan-run for mile after mile, praying that it would not end in some enormous crevasse and also that we would be able to get out of it before it came to the snout of the glacier. Luck smiled again, and there, at exactly the right place, was a snow ramp which allowed us to get out and make our way over the Piedmont to the Stranded Moraines.

Half a mile away was a black dot by a pressure ridge on the sea-ice, the first seal of the season, and soon that seal was a mountain of dog-tucker and seal liver was simmering on the primus. The sun flickered up over the horizon for the first time in days and icebergs shimmered in the mirage, the temperature was only -8F and we put our iced sheepskins outside to dry. I sat on a ration box chewing a cube of blubber, and pushed my anorak hood back for the first time in six months and laughed aloud.

“What’s the joke?” asked Richard.

“Oh, I was just thinking how good life was, and then how quickly one’s standards change!” Life wasn’t that good, the snow on the sea-ice was salt and made truly awful cocoa. The sled dragged like concrete for the forty miles home on that salty snow. We should have stopped and iced the runners more often, but the ice cracked off the steel runner capping. They say frozen porridge is better! Around Cape Armitage we were progressing by fifty-yard spurts but finally, wearily we made the dog lines and Bob Miller cheerily helped us feed the dogs.

That hundred yards up the snow slope and over the tide crack seemed a long, long way, but finally, finally we lowered ourselves into chairs and made a cup of cocoa. Ayres and Co were off to Cape Crozier and no one asked us “How did it go?”

Cranfield came in from the air dressed in heavy blue nylon overalls. I grasped a handful and pulled him over my knee and laid into his rear end.

“Cranfield, what is that thing on a wire you must reel in before beating up poor dog sledgers? Say “Sorry”!”

“Oh, God! No!” cried Bill. “My aerial! I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’ll never do it again!”

A day or so later, about the 25th September, Ayres, Douglas and party were due back from Cape Crozier and their Spring Journey. It was a miserable day with wind raising the drift and I periodically went out with the glasses to anxiously watch the progress of the rows of tiny dots across the deep snow of the Windless Bight. When they came in round the Pressure I went down to the Lines to help span and unload, as when they came into the Mess Hall, Ayres was showing his age, his face fallen in and his beard solid with ice, as was his jersey.

“How did it go, Harry?” and he stirred his cocoa for some minutes before replying, “Not bad, really!” which meant it had not been good. Later in the sledgeroom he opened up a little, we had known each other long enough that I could be trusted, besides I was almost a Guide.

“It was a bit of a bastard, actually,” he admitted. “Bit of a bastard when the tent pole broke, eighty knots and dark at that! We had to get out between the inner and outer tent and splice the pole with a couple of ski-poles.”

Unfortunately, someone else overheard this admission of weakness.

“Old Harry must be cracking up,” sneered that worthy to me later. “Christ, can’t he handle a broken tent pole in a bit of wind ?“ Well, Apsley Cherry-Garrard wrote “The Worst Journey in the World” of a spring trip to Cape Crozier, only a little earlier in the year and the Antarctic has not changed. Cherry, Wilson and Bowers, “the hardest man to ever come South” had their tent blow away on that same spot, and Cherry was quite adamant that had they not found it caught round a boulder they would have all died there! Of all the odd aspects of TAE, the reluctance to admit any latitude for failure was perhaps the strangest.

©2007 - may not be reproduced without permission