15 – Plans for Fieldwork

By this time, though our position out on an off‑shore island had prevented us doing any field work other than the two weeks on the Skelton traverse, from the air and through field glasses we had built up a pretty good idea of the whole topography from the Mawson Glacier up the coast, down to the Darwin Glacier south of the Skelton and the place buzzed with speculation. Early experience with aerial mapping in the Antarctic had shown it to have little value without ground control. Sir Hubert Wilkins, and Lincoln Ellsworth had both discovered "Straits" cutting across Graham Land where the land is actually 8000ft high, and Ellsworth and Byrd had both mapped from the air non‑existent mountain ranges or ranges more than a hundred miles out of position. Operation Highjump had found in 1947 that they could not locate some of their photographic flights within a hundred miles and obviously any mapping we might do at least had to be at least partly if not totally done from the ground.

By this time, though our position out on an off‑shore island had prevented us doing any field work other than the two weeks on the Skelton traverse, from the air and through field glasses we had built up a pretty good idea of the whole topography from the Mawson Glacier up the coast, down to the Darwin Glacier south of the Skelton and the place buzzed with speculation. Early experience with aerial mapping in the Antarctic had shown it to have little value without ground control. Sir Hubert Wilkins, and Lincoln Ellsworth had both discovered "Straits" cutting across Graham Land where the land is actually 8000ft high, and Ellsworth and Byrd had both mapped from the air non‑existent mountain ranges or ranges more than a hundred miles out of position. Operation Highjump had found in 1947 that they could not locate some of their photographic flights within a hundred miles and obviously any mapping we might do at least had to be at least partly if not totally done from the ground.

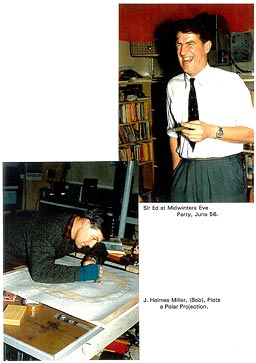

Sir Ed took to retiring to his office for days on end, emerging periodically to demand questions such as; "George, if you have two sledges and two men and forty days supplies how many miles a day can you cover?" Plainly, Our Leader was Up to Something.

Some of his enquiries were not treated as seriously as he might have liked as that warped kind of humour that always emerges when a small group are confined, was becoming all too well established. Oddly enough, Bates and Ellis seemed to be forming one particular Folies a Deux, and once Sir E came up as we sat round a Mess Table.

"Jim," he said to Bates. "If we take tractors part of the way up the Skelton, could we weld on some sort of steel extension out in front so a tractor couldn't go down a crevasse?"

Bates considered this seriously. "Difficult." he said, "To be strong enough it would be dam' heavy and it would have to be high in the air to stop it foulin' sastrugi. Mind you," he added, eyes brightening with that Mad Inventor's look, "You could have a sort of built‑in long bar fired by a mercury‑level switch, tractor breaks through, Bang ! And it's into the far side of the crevasse!"

Ellis's eyes also gleamed, "No! No! An explosively‑fired anchor on a cable!" he said excitedly.

"Blam!" cried Bates. "Fire 'er out, automatic electric winch, haul'er over and away!"

"Away, away, awayee!" sang Ellis.

"On to The Pole!"

"Rule Britannia!" and they leaped up in ballerina pose, dramatically pointing;

"On to the Pole!"

Sir E stood up so savagely his chair fell to the floor. "I wish to God some of you clowns could be serious for once!" and stamped off to his room, which did little to stifle the chuckles. Finally there Came a Day which my wretched diary does not even pinpoint, perhaps after Midwinter, when Sir Ed emerged from his office and with an air of righteous pride, pinned to the Bulletin board a long and complex plan of the disposition of the entire field staff for the coming summer. We gathered round the board excitedly, This was It! My eye quickly picked out:

" Northern Party. Brookes (Leader), Gunn, Warren, Douglas. Two dog teams. To leave Base approx October 1. up coast. To leave coast for Plateau via MacKay Glacier about Nov. 1. To receive resupply Upper MacKay Glacier by air approx Dec.1. To reach Plateau Depot, Skelton Glacier approx Jan.1. To be at Lower Skelton Depot by Feb. 1."

Richard and I caught each other’s eye and solemnly shook hands and then with Warren and Douglas. This was what we wanted, at most I had hoped for half as much! There was much, much more. The Depot‑laying party for the support of the T.A.E. Crossing‑Party was to a be a combined effort with four tractors and a weasel, lead by Sir E himself. Harry Ayres and Roy Carlyon were to go with them as far as a Depot to be laid 470 miles out and then branch off to the east to map the Darwin Mountains.

George Marsh and Bob Miller were to stay ahead of the tractors until D700, 700 miles out, and then turn east to the Queen Maud Mountains.

It was a historic document, I wonder if it survives? It was perhaps the most comprehensive and daring plan of field activities ever proposed in the history of polar exploration and its proper place is in the Scott Polar Institute. A copy was telexed to the Ross Sea Committee in Wellington and a reply was not long forthcoming! It too, in its way, was a historical document, a monument to bureaucratic caution and indecision! Sir E did not exactly roar with rage, but with a face like thunder he stamped out and pinned the offending document to the wall with a blow of the fist!

"My God!" cried Mulgrew, "Come and look at this bloody rot!" and we gathered round in consternation. In brief, it completely rejected the plan and directed that our entire field staff ie, of twenty men, should concentrate on establishing Depots.

"However," it concluded in a tone of pomposity that could almost be heard, "A limited amount of exploration may be carried out in True Antarctic Tradition, within a distance not exceeding fifteen miles of the Depots!" There was of course, no land within fifteen miles of the Depots! We roared with laughter, we booed, we jeered! The phrase "In True Antarctic Tradition" was to became a catchword for doing nothing! Within minutes Sir Ed came forth again and banged up his reply, which said in effect, "The deployment of Field Personnel is best left in the hands of the Field Executive who are at least in a position to appreciate the problems and capabilities of the people concerned. This matter may be discussed further." (which it was not).

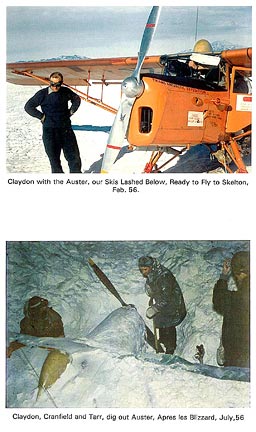

We cheered, we whooped, we guffawed. "That's bloody telling the twits, Ed!" we cried. Thus did Edmund Hillary lay himself, his career, his future, squarely on the line. In his book he merely observes, "I continued as though the reply had never been received." We used to refer to him with a touch of sarcasm as "Our Leader", (considering, in our juvenile arrogance, that we needed little leading), but a real Leader is there to make difficult decisions and stand by them, and by doing so he won our respect and support. He was used to running his own show, did he resent the interference of a group of desk‑bound fuddy‑duddies? Was he determined that we should have a chance to complete some useful work and, for some, carry out ambitions which had been smouldering for many years? Did he consider the difficulty of driving a demoralised crew on a task many of them considered unnecessary and unworthy? The Ross Sea Committee, had, like all committees, covered themselves nicely, if there was an accident, if any part of the plan failed, it was not their fault, it had been done in defiance of their orders. Had there been a single accident, Sir Edmund would have been pilloried by Press and by Parliament, did he consider this? That magnificent man has never condescended to explain, either then or at any other time, we shall never know. Obviously, the greatest weight fell on our Air Support Group and I would love to have been privy to Claydon's reactions when Sir E first approached him, (as he must have, quite early in the planning). Suddenly, our single Beaver was going to have to fly out at least twice as many fuel drums as had been originally planned as well as make the supply drops for three previously unplanned survey parties. Of course, we simply didn't have the fuel but a telex went to June Drew, our assistant secretary in Wellington, who had once worked for British Petroleum, and it was not long before an assurance was received that BP would have the extra fuel sent down on the first ship. It helps to have a major company like BP behind you and whatever we did or needed, BP were right there!

We cheered, we whooped, we guffawed. "That's bloody telling the twits, Ed!" we cried. Thus did Edmund Hillary lay himself, his career, his future, squarely on the line. In his book he merely observes, "I continued as though the reply had never been received." We used to refer to him with a touch of sarcasm as "Our Leader", (considering, in our juvenile arrogance, that we needed little leading), but a real Leader is there to make difficult decisions and stand by them, and by doing so he won our respect and support. He was used to running his own show, did he resent the interference of a group of desk‑bound fuddy‑duddies? Was he determined that we should have a chance to complete some useful work and, for some, carry out ambitions which had been smouldering for many years? Did he consider the difficulty of driving a demoralised crew on a task many of them considered unnecessary and unworthy? The Ross Sea Committee, had, like all committees, covered themselves nicely, if there was an accident, if any part of the plan failed, it was not their fault, it had been done in defiance of their orders. Had there been a single accident, Sir Edmund would have been pilloried by Press and by Parliament, did he consider this? That magnificent man has never condescended to explain, either then or at any other time, we shall never know. Obviously, the greatest weight fell on our Air Support Group and I would love to have been privy to Claydon's reactions when Sir E first approached him, (as he must have, quite early in the planning). Suddenly, our single Beaver was going to have to fly out at least twice as many fuel drums as had been originally planned as well as make the supply drops for three previously unplanned survey parties. Of course, we simply didn't have the fuel but a telex went to June Drew, our assistant secretary in Wellington, who had once worked for British Petroleum, and it was not long before an assurance was received that BP would have the extra fuel sent down on the first ship. It helps to have a major company like BP behind you and whatever we did or needed, BP were right there!

I am sure Claydons' reaction would have been much the same as if OC Bomber Command had told him during the war, "I say, Claydon, we want your chaps to carry out two missions a day on Rabaul for the next month, think you can do it?" and Johns' reply would have been, "Oh, I think so!" And this was the man who flatly refused to fly me fifty miles to find the Dry Valleys! Had there been no opposition from the Ross Sea Committee, we might have stopped to ponder on the problems of our small field parties working up to a thousand miles apart, a long way when you rely on a single aircraft.

"It really isn't on, y'know," said Harry Ayres, hammering on a bent piton in the sledge room.

"What isn't?"

"This idea of Ed's. Two men on their own, six hundred miles out. It's a bit light. It isn't on, really."

"We can handle it." said I with all the arrogance of youth.

"Maybe," he sighed, peering up at the karabiner, holding it up to the light, and chewing on his home‑made. Perhaps he was thinking of the Adams' rescue or of a dozen others. "Maybe, but it's a bit light all the same. A bit light, I reckon!"

The nub of it all of course was plain pride. Who was going to go snivelling to Sir E and say "I don't think I can handle it!" Not one of us, to be sure.

The winter progressed in a round of working on tractor repairs, photography, feeding dogs, digging snow, building up the work‑shop, the occasional run with the dogs on a moonlit night, packing food boxes for the following summer, there was no end to the work. On the 3rd of August my diary records:

"T down to ‑54 deg, put right brake drum back on Aggie's left wheel and removed wheel and drum from right. Took off right axle and brake‑shoes, had a go welding cap back on brake drum. After dinner Guy and I sawed up two seals and fed dogs, quite hard work. Ken Meyer arrived over (from the American base) with two new movies, "Caine Mutiny" and "Genevieve". Swotted Astro Nav."

I believe this was the day I needed some kero for cleaning and Bates told me of a 12‑gallon drum at the dump which I brought back by tractor to the garage. I opened it and it stood steaming quietly, its contents still at ‑54deg in the heated garage.

"What's this?" said Sir E, coming up. "Kero?" and put his finger in it! At times I spent days in the Darkroom which I had enlarged and lined, printing up to fifty pix at a time from some of our recce flights and by careful temperature juggling, was now getting reasonable negatives developed, but I still envied Ponting his facilities in 1910. Others began to get interested so at times the darkroom was in continuous use. It seemed incredible that we should have brought an enlarger and glazer without having a darkroom planned, and with only about 20 sheets of photographic paper! Fortunately Ken Meyer, the photographer at Hut Point was engaged to a Christchurch girl and looked on himself as an adopted Kiwi and gave me 500 more. It was just as well as one could never be quite sure whether a roll of film was usable or not due to camera freezeups and other problems.

The shortage of official film and printing paper occasioned some debate, John Claydon pressing for a greater share because of the many interesting topographic features the pilots (and usually no one else!) saw. Unfortunately, he pressed his case too hard, and the usually mild Bob Miller snapped:

"I don't think your photographs are that good anyway, John!"

Later, Claydon was showing me his neat book of small contact prints of unusual crevasses patterns in the upper Mulock Glacier, and some of odd‑looking nunataks and I made encouraging noises.

"They look very good John, keep it up!" Claydon looked pleased.

"Oh, do you really think so?" Then, "Bob doesn't seem to think they are!" I blinked, and then it dawned. Our blood and guts Flyboy had been hurt by Miller's thoughtless remark!

Between times we made thin‑sections of rocks and peered at the minerals through an ancient brass microscope that had been loaned us. It was exactly the same model that Sir Frank Debenham had used in 1910. A well‑equipped scientific expedition we were not! Even now, people have two common questions about spending a winter in the Long Dark.

"What did you possibly do all that time," and "Did you have any psychological problems?" Regarding the latter, one does hear of some strange stories, such as the winter of Finne Ronnie's expedition on Stonington Island in about 1948 and related by Jennie Darlington in "My Antarctic Honeymoon". One of the members whom I had met aboard the Edisto told me, "The day there wasn't a fist‑fight before breakfast we looked on as real peaceable!"

One man went a bit odd over at Little America and walked off alone to end it all, and sat down in the snow a few miles away. Unfortunately the temperature stayed above zero and after a couple of days he became hungry and walked home! The physiologists fell upon him with glad cries and subjected him to every test they could devise! At Little America they also built a sauna and the men began competing as to how big a temperature change they could record between being in the sauna and jumping outside, the human body taking several minutes to freeze! In the spring Admiral Dufek was to visit. "Some of the men have gone a little strange, Admiral," they warned him on the walk in from the airfield. "But if you see anything odd, just pretend not to notice!" It was a cold day, about ‑30, and at the door of the Base suddenly half a dozen totally naked men burst out dancing in the snow and waving,

One man went a bit odd over at Little America and walked off alone to end it all, and sat down in the snow a few miles away. Unfortunately the temperature stayed above zero and after a couple of days he became hungry and walked home! The physiologists fell upon him with glad cries and subjected him to every test they could devise! At Little America they also built a sauna and the men began competing as to how big a temperature change they could record between being in the sauna and jumping outside, the human body taking several minutes to freeze! In the spring Admiral Dufek was to visit. "Some of the men have gone a little strange, Admiral," they warned him on the walk in from the airfield. "But if you see anything odd, just pretend not to notice!" It was a cold day, about ‑30, and at the door of the Base suddenly half a dozen totally naked men burst out dancing in the snow and waving,

"Hi, there, Admiral!" for a minute or two before vanishing.

"You see what I mean!" the guide said gloomily.

"God Almighty!" said Admiral Dufek. "How the hell long they been like that?" Most of the men on T.A.E. simply got on with their job and one can't quarrel with men who do that so we had very few disagreements and I don't believe there was a single case of two gentlemen agreeing to differ and stepping outside. Mulgrew, like many shortish people was inclined to brag, especially about his judo prowess and one day told a rather sickening tale of a fight with some Merchant seaman where he had deliberately broken a man's arm. He claimed to be a Black Belt which meant that neither size nor number of opponents made any difference. We happened to be in the galley together afterwards.

"You know, Peter," said I. "That was a lot of rot, a good big man will always beat a good little man, Judo or no Judo."

"Judo means size makes no difference at all," he said looking at me in a way I didn't particularly like. "You use his weight against him! I could handle you easy, you big slob!" he added.

I kicked his feet from under him and he landed on his arse on the floor in a way that shook A hut to the foundations. He immediately hooked a toe behind my ankle and launched a kick at my knee, an action somewhat less than friendly. It is meant to dislocate your knee but was a trick so old it had grey hair. I simply turned so his kick hit behind the knee. I put a foot on his neck.

"Peter, old son!" I said pleasantly. "If you ever try anything like that on me again, I'm going to kick your head off. Now get up and get to hell outa here!" He scrambled to his feet, red‑faced, and left without a word and avoided me thereafter, which suited me well enough.

Some people find both the 24‑hour daylight in summer and the 24‑hour dark difficult to deal with. They seem unable to set themselves a regular rhythm and stay up pottering about for 30 hours and then sleep for 48 and become totally disorientated. This means others have to do their work. We mainly followed regular hours though few as conscientiously as Ellis who at the stroke of eight throughout the winter arrived at the Mess Hall, and left at exactly 8:48 for the garage, spent exactly 15 minutes at Smoko, came in at exactly 12:30 for lunch. Most of us lesser mortals were guilty of taking the odd extra 30 minutes or even more at some smoko breaks.

On a later expedition we had a bad case of a man not pulling his weight and my Second‑in‑Command came up to me thiswise:

"What are we gunna do about His Useless Nibs?"

"Bit of a problem alright, yesterday he got out of bed at 4pm, hasn't done a damn thing for days!"

"How about I work 'im over a bit? Coupla clouts across the ear works wonders with some o' these misfits!"

"Maybe, I did give him a hint yesterday."

In disappointed tones, "Y' mean y' done 'im over?"

"Oh, no! I just picked him up by the shirt‑front and nailed him to the bulkhead and sort of suggested he should do better."

"Didn't do much good, did it? Bet if I kick the tar outa him he won't forget in a day or two!"

I though for a minute or so, but I knew it would not be just a couple of clouts, it would be cold, merciless hammering delivered with the contempt of one to whom duty meant everything, to that most worthless of beings, one who had let the team down. And not many men can psychologically take being beaten up in an atmosphere of total contempt. "Look, I know it works in some cases but I really don't think this fella has got it!"

"So wotta we do?"

"Send him home on the next plane." And we did.

Not all nations handle their psychologically depressed in the same way but our, admittedly rough and ready, methods seem to have merit. I try to imagine going to Our Leader and confessing that I felt unable to withstand the psychological and mental strain of a Winter on the Ice. I try to imagine the lowering brows, the ill‑concealed impatience, the growing exasperation merging into seething contempt.... I say I try, but the mind boggles, it positively flounders.... My psychoneuroses are firmly established and robust, thank you, but not that robust. So we had no psychological problems, they would not have been allowed!

Sir E had few occasions to lower the boom on any member, one of the few involved Mulgrew, who usually shared a tent with him in the field and was something of a crony which perhaps made the offence worse. One of the diesel generators had developed a wiring fault which was Mulgrew's responsibility and Bates took the opportunity to give it a valve grind. A week later Sir E noticed it was still in pieces.

"Why isn't the generator back in commission, Jim?" he asked curtly.

"Ask y' bloody friend Mulgrew," said Bates equally shortly. "Can't put t'gether tills he's fixed th' bloody wirin'!"

Mulgrew happened by. To give him his due, he was a most capable electronics and radio man and had a sense of duty second only to Lt.Cmdr. Smith ex Takao.

"Peter!" said Sir E in the voice we normally associate with a Herr OberstLeutenant on a rampage. "Why the hell isn't the generator fixed?"

Peter stopped dead, turning pale. "Oh, my God! Hell! I'm sorry Ed, I must have‑‑, well I just ‑ forgot!"

"Forgot!" roared Sir E. "You, the Chief Electrician and you say you forgot, you ‑ !" He strode up and down tearing off a royal strip while Mulgrew, pale as death stood rigidly to attention. Had Sir E slashed him across the face with his gloves I am sure Mulgrew would not have moved a muscle. He was a Naval Lieutenant, (Sir E was in fact of superior rank), he had been in dereliction of duty and had absolutely no excuses.

It was a curious scene, we tend to think of such behaviour as Prussian but we conveniently forget how closely related we are to the Germans. Read any German account of the war, and their rueful admiration of our iron discipline especially in the Royal Navy.

"Had we learnt anything from the British," said U‑boat Commander Spiess of the German mutiny in 1918, "We would have gone alongside, boarded and hanged the mutineers!"

Differences of this kind were however rare and the winter passed unusually amicably as expeditions go!

©2007 - may not be reproduced without permission