3 – Planning the Ferrar Glacier Journey

The next item on the program, having now found by air only one passable vehicle route from the coast up to the Polar Plateau through the Victoria Mountains which extend right across the continent for about 2000 miles, was to take a closer look at Scott's 1902 man-hauled sledge route up the Ferrar Glacier immediately across the Sound. From the air it seemed icy but quite flat, narrow and smooth except for the thawed and moraine‑littered lower two or three miles which had at first led the 1901 "Discovery Expedition to believe it was impassable. Scott later found that if one kept close to the north bank in the shade of the Kukri Hills, sledges could be manhauled and carried up to the better going. Though Scott and his men seemed to have spent an unforgiveable amount of time falling down crevasses higher up the glacier, it was one possible route for dogs sledges if not vehicles and I was supposed to look at it in detail.

The next item on the program, having now found by air only one passable vehicle route from the coast up to the Polar Plateau through the Victoria Mountains which extend right across the continent for about 2000 miles, was to take a closer look at Scott's 1902 man-hauled sledge route up the Ferrar Glacier immediately across the Sound. From the air it seemed icy but quite flat, narrow and smooth except for the thawed and moraine‑littered lower two or three miles which had at first led the 1901 "Discovery Expedition to believe it was impassable. Scott later found that if one kept close to the north bank in the shade of the Kukri Hills, sledges could be manhauled and carried up to the better going. Though Scott and his men seemed to have spent an unforgiveable amount of time falling down crevasses higher up the glacier, it was one possible route for dogs sledges if not vehicles and I was supposed to look at it in detail.

Detail meant on the ground, which meant I would have to have one or two people to go with, a tent, sledge and stores and organise a helo ride over the water to the lower glacier. This could only be done at the ships, so after spending a day or two investigation perma‑frost polygons at Hut Point, I thumbed a helicopter and returned to the "Edisto" with a call at Scott's old 1910 Hut at Cape Evans en route. There were several civilians lurking about in the various ships of the fleet but none seemed madly keen on a couple of week's walk through the mountains even to look at some quite classical rocks. I located a reserve of a couple of dozen cases of Army C‑Rations on board the "Wyandot" which solved one problem.

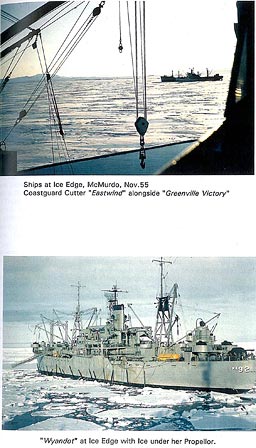

A certain Chuck Lewis on the "Wyandot" claimed to be a geologist but seemed to think of mobility in terms of helo rides, not feet. I walked out to the parked Skymasters to have a coffee with Jorda and Donavan and the crew who were living in somewhat primitive conditions waiting for someone to give them orders. I admired their patience, a parked aeroplane on four feet of seaice being at best a cold habitation and passed on to the Coastguard Icebreaker "Eastwind" also moored to the ice, to see one, Commander Cadwallader. It seemed the Admiral was not happy about everybody hitching rides on passing choppers and had ruled that Cadwallader must approve flights. He turned out to be a tall, craggy‑faced officer from New England who had spent time in an Embassy in Kashmir and was, for an American, unusually active. We had a good deal in common.

"I'm going to go over to the Taylor Dry‑valley ( which lies immediately north of the Ferrar Glacier) myself tomorrow," he said. "Would you care to join us? It might help you!"

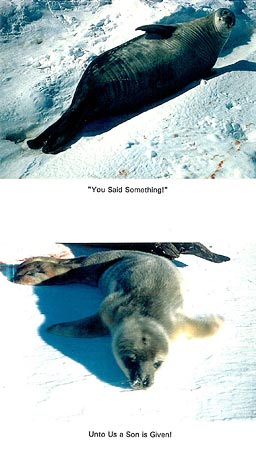

Would I ever! I mooched around the ice‑edge back to the "Edisto", idly kicking the bums of a number of great gross Weddell seals which lay in total idleness at the ice‑edge. Why should they be able to laze about when I had to strive from dawn to dark? (the next period of dark being some months in the future).

In the middle of the night I was wakened and told to stand by, one Lt. Entrican returning from a photographic flight in a P2V to the Pole of Inaccessability had lost a motor and there could be a rescue call! He scraped over the mountains on one engine and landed without mishap. It turned out he merely had a defective magneto and had he switched it off and run on the other one there would have been no problem!

"What a prune!" I thought when finally told to stand down at about 4am. As a result I woke up late in the morning, the 7th, and barely made the flight‑deck, clutching camera, in time. Thirty seconds later we were gyrating over the water to the "Eastwind" where we picked up Cadwallader, Father Linehan (a Jesuit priest and seismologist) and Chuck Lewis and were on our way over the Sound. A belt of fog lay across the coast but we landed four miles up the valley. There was amazingly no snow, the floor of the valley was formed of old rolling moraine dumps, now covered in sand and gravel pocked by permafrost. Two wall‑sided glaciers flowed into the Valley from the north and spread out into bulbous toes on the valley floor. Meltwater streams flowed down the valley and formed small lakes. Everywhere sandblasted glacial erratics, some ten or twenty feet high of granite, gneiss, dolerite and kenyte volcanics littered the ground. About ten or fifteen miles west the valley curved south‑west around a dome that Debenham and Taylor in 1910 had called the "Nussbaum Riegel"!

Cadwallader and I walked down to the Commonwealth Glacier, jumping over a meltwater creek over boulders on which Cadwallader slipped and fell into his knees, at which I laughed loud and long. With staring eyes we walked round the hundred‑foot high ice cliffs and marvelled at their steepness, and then around the eastern side and uphill until we could walk out the surface of the ice which was cut by ablation pits and thaw channels. Then back over the stream, now falling as the sun moved south behind the Kukri Hills.

Cadwallader had a typical hillman's gait and I became curious.

"You walk pretty well," I observed. "Where did you learn?" and he told me a little of his excursions in Kashmir. The dry Taylor Valley seemed an ideal Base site if one had a grader to form a tractor trail up to the glacier at the head of the valley and down to the sea. But your plane would have to land on wheels. Interesting thought! What did not cross my mind at the time was, that if your expedition used dogs, the dogs must have clean snow of which there was not much.

Back aboard I soon went visiting round the ships again finding Bob Forbes, the geology professor from Fairbanks, Alaska, Bowers having carried out his threat to kick out all non‑effective personell from the base‑site. I tried to enthuse him into a walking trip up the Ferrar Glacier. He was by far the best kind of person to do such a trip with, being not only a Professor of Geology but an Alaskan one at that with an incredible fund of stories of adventures around the Arctic shore. The "Edisto" was due to leave for Cape Adare in three days time and I was going to have to move anyway. It would be a nice two‑week trip I suggested. Forbes was a little more cautious, he heard me out and rocked with laughter.

"You know, Howard," turning to the inevitable and usually silent Howard Parker, "I like this guy! He is so bloody naiive, he reminds me of when I was, oh, about four years old. He says we will walk off through the mountains, and in a couple of weeks The Navy will pick us up! The Navy, my God! He talks as though The Navy was composed of people and not the most appalling collection of clowns, klutzes, and knuckleheads ever assembled!"

"Oh, come on!" said I, mystified. "John Cadwallader is a first ‑class chap and a really competent officer!" Bob was unimpressed.

"So he is, just the kind of guy The Navy will put on mess duty or send to Rio next week. Do you think that some other guy might just happen to remember, 'Oh, yes, there was that bunch to be picked up off a glacier someplace.'?"

"I don't see why not," said I, baffled.

"I'll tell you," said Forbes. "Once upon a time, in '43, I was an eager‑beaver paratroop lootenant. The Navy said 'We, the Navy will drop your regiment in a deserted area in the middle of Sicily. You will secure the area, and We, The Navy will land three days later and you will link up'.

"Yessir, Yessir" sez I. So they dropped us smack in the middle of a Kraut army. More than half my regiment was wiped out, when I ran out of ammo, some kindly Herman said "Handen hoch" instead of shooting me. The Navy didn't land for three months at some other place. Ever since then I have this strange distrust of The Navy." and he laughed again in a way that did not induce us to join in.

"Prejudice, prejudice" I said kindly. "The U.S. Airforce made a slight miscalculation before Monte Cassino and wiped half the New Zealand Army, does that make Trigger Hawkes a clown?"

Unhappily the redoubtable Forbes had conceived an inordinate dislike of the unfortunate Trigger probably because of the Otter crash and the conversation degenerated into one of those hilarious character assassination sessions. Forbes finally admitted it might work if we could get a really reliable radio and leave it at the foot of the Ferrar. Conversation turned to Bear stories, Forbes having been treed by a large number while working in Alaska and had some confrontations with the Polar variety while in the Arctic. It seemed a pity there not a few bears at McMurdo to liven things up!

I mooched off finally and got hold of the only mobile radio the US navy possessed called an ANG‑9, rather like our old wartime ZC‑1's. An obliging Weasel driver maintained a conversation which went fine as long as he was with shouting distance. As soon as the Weasel disappeared over an ice ridge a mile away, all communication ceased. I said some naughty words.

When I had learnt more about radio, I would have experimented with a dipole aerial before writing them off, part‑wave whips not being very efficient.

Back on "Edisto" I had to tell Lt. Field, our chief helicopter pilot, to scrub my helo ride to the Ferrar until some logistic problems were worked out, "Logistics" being a word Americans like. It was a current buzz word.

There had been a distressing accident, a heavy D8 tractor had been unloaded onto the ice, more by accident than design and it was finally decided to drive it to Hut Point. An old Navy Chief whom I knew well drove it as far as the crack in the ice out from Cape Royds and as it crossed on a timber bridge the ice-edges broke away and it fell through into fifty fathoms of water and my old friend was lost. About this time also the SeeBee, Williams, was lost through the ice in a Weasel close under Hut Point and the ice‑runway was to be named Williams Field after him!

There had been a distressing accident, a heavy D8 tractor had been unloaded onto the ice, more by accident than design and it was finally decided to drive it to Hut Point. An old Navy Chief whom I knew well drove it as far as the crack in the ice out from Cape Royds and as it crossed on a timber bridge the ice-edges broke away and it fell through into fifty fathoms of water and my old friend was lost. About this time also the SeeBee, Williams, was lost through the ice in a Weasel close under Hut Point and the ice‑runway was to be named Williams Field after him!

The Admiral then ordered a stop to all vehicle movements up the Sound as the ice was obviously weakening. As a result, "Glacier" punched out a narrow channel a good ten miles closer to Hut Point, but there remained a problem, it was so choked with brash and broken ice that only an icebreaker could use it. The "Edisto" was called in as a ferry, cargo being offloaded from the "Wyandot" and the "Greenville Victory" (which were cargo ships), and dumped on our flight deck to be ferried up the channel. Cargo flow slowed to a trickle.

On the 11th of January a light easterly wind began drifting the mass of ice from along the Erebus side of the sound over to the west and the channel began to close. I went up on the bridge as we roared and grunted and backed and charged. "Edisto" could pump about a quarter million gallons of fuel forward, aft, port and starboard to roll ship, but finally, the ice squealing along her side, we ground to a permanent halt. The OD was a nineteen year‑old Lieutenant J.G. ("Junior Grade") with whom I was sharing cabin, and his usual assumed phlegmatic calm vanished.

"Oh, ‑‑‑‑ !, said he, "I got her stuck!" We went off to wake the captain who lay in his bunk and yawned.

"Got her stuck, have you Son? Have you tried rolling and pitching her?"

"Yessir! Tried all that!"

"OK then, get the explosive team over the side." Explosions shattered the ice, and struck the hull like depth charges and I fully expected them to start some plates. By this time pressure had squeezed us up out of the water and we lay on a thirty degree list, but the explosives opened a hole, the engines roared again and we began to progress again slowly. Near the ice‑edge and the rest of the fleet, hooters were sounding and several ships were screaming for help. "Wyandot" had great blocks of ice round her single propellor which was now half out of water, and could not move. "Edisto " stuck her bow on the ice and washed it all clear with her wake and "Wyandot" moved off out into the safer clear water.

The "Nespelen" then started hooting and I stared at her curiously. The air was calm and apart from a slab of sea ice a few hundred feet long laying along her starboard side she seemed to be in no trouble. Then my friend, the OD pointed out the problem, her entire side was crushed in, ten frames had given way, an engine lay over several feet, and some 14,000 gallons of aviation gasoline poured out through a twenty‑foot rip in her hull. More hooters sounded. "The smoking lamp is out on all weather decks" came over the Tannoy, a slightly archaic way of saying, "No smoking topsides". (A lamp used to kept lit on deck for the seaman to light their pipes. they were not allowed matches becaue of the fire danger on wooden vessels). A single cigarette but tossed over the side would have set the sea on fire! Even the massive ships suddenly seemed frail things.

Again this was all very interesting, but personally I couldn't really have cared that much if the entire fleet was sunk, I had my own little war which meant getting twenty miles over now rotten sea‑ice over to the Ferrar Glacier for a closer look. Understandably, The Navy now had others things on its collective mind. The other two New Zealand observers had turned up, Dr Hatherton, a lanky geophysisist of Yorkshire origins and friend Wilbur Smith, Lt.Cmdr,R.N., DSO & Bar etc,etc,etc. They had engaged in a (to me) somewhat eccentric journey walking across the sea ice pulling a light plastic rescue "Banana" sledge and had visited Butter Point and the Dailey Is. The sea ice by now was rotting and covered in thaw pools and they spent days recovering from trench feet. Unfortunately a television reporter called Halligan had elected to go with them, and he not being very fit, had collapsed and they ended the last twenty miles having to drag him and his cameras on a sledge. They were not very interested in my little discoveries, Smith pointed out scathingly that I had only seen my Skelton Glacier route from the air, that in any case the Base was to be located at Butter Point, and the route to be used to the Icecap lay up the Ferrar.

Actually, finding routes was my pigeon, and Smith was supposed to observe ship movements but I think he had ambitions of being on the shore party. As Butter Point was simply a sloping ramp of thawing ice, just what a Base could be built on puzzled me.

Truth to tell, neither were my beau‑ideal of tramping party companions, Smith in my possibly biased view being both totally ignorant of matters terrestrial and difficult to get on with, as, while undoubtedly hell on wheels in any action requiring boarding, cutlass in hand, he obviously was out of his depth on shore. On the positive side, at least they were prepared to go on a two‑week trip up the Ferrar and no one else was and I already had a dozen boxes of C‑rations put aside, and a helicopter jacked up. I still had considerable doubts, friend Smith might have been a war hero, but one gets in time to recognise the Death Wish, and unless I was much mistaken, he had a bad dose of it or at least was remarkably casual about personal survival. Laudable though this ambition might be, in fact to be positively encouraged in some, the Wishers are sometimes just a little too casual as to who they take with them to the eternal shades.

"If the Queen ordered me to cut off my right arm, I would do it immediately!" said Willie on one occasion, eyes flashing. I wondered audibly what the Queen would do with such a curious present, which began something of a cooling in our relationship. Necessity however, makes strange bed‑fellows, or rather tent‑fellows and on the l6th Jan. Chuck Coustanza lifted us plus two banana‑boat sleds across the Sound and landed us on the ice of the Ferrar a few miles from the sea, with a promise to pick us up on the 27th. of January, 1956. As it turned out, ex‑paratrooper Forbes had remarkably accurate insight both into the future and to the workings of The Navy's collective mind!

©2007 - may not be reproduced without permission