2 – An Air Interlude, from David Glacier to the Beardmore

(and we discover the Skelton Glacier Route to the Ice Cap)

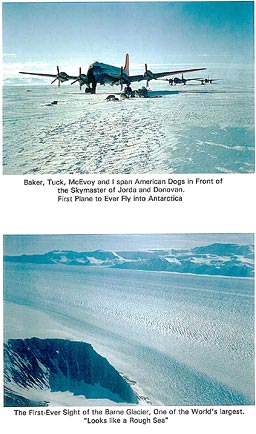

The Weasel left me alongside Hank Jorda's Skymaster which still stood forlorn out on the ice in the middle of McMurdo Sound, though by now it had been joined by the second Skymaster and two twin-engined P2V Neptune long range bombers. I climbed into the cabin, pack and ice‑axe in hand and Jorda pumped my hand.

The Weasel left me alongside Hank Jorda's Skymaster which still stood forlorn out on the ice in the middle of McMurdo Sound, though by now it had been joined by the second Skymaster and two twin-engined P2V Neptune long range bombers. I climbed into the cabin, pack and ice‑axe in hand and Jorda pumped my hand.

"Now we can go, but first we have to make a little flight down to the ships to get fuel from the 'Nespelen', three feet of ice they tell me! Three feet, my God, am I to land this damn' plane on three feet of ice? Bernie Boy, bring that iceaxe and we go and look at the runway."

He paced out the take‑off path which was no longer smooth, the wind having ridged the snow into drifts, continuously muttering, more to himself. "Three hundred fifty yards, do we have the nose wheel up? Bernie Boy, prod that drift, two feet, you say? My God, I lose my nose wheel, we have to start further back. What have we here? Only a one‑foot drift, Ok, no trouble at say, ten knots."

Finally we flagged a runway along which we might get off the ground or rather sea‑ice.

"Old Hank is a bit of a worrier!" grinned the irrepressible Donovan, but I was already developing a liking for (and trust in) the serious little Swede. A drop of petrol fell from a wing;

"A petrol leak, my God! Rudy, get out here, we got a petrol leak!" The middle‑aged crew Chief lumbered out and counted.

"Four drops a minute? Forget it, Hank!"

"OK, OK, start the damn' putt‑putt!" A small generator clattered and one by one the four Pratt & Whitney radials rumbled into life. Another gangling crewman, Jim Swedener, roamed about the cabin.

"What do you do?" I asked, curiously, as he was obviously neither pilot, navigator or engineer.

"I'm the Bombardier."

"Bombs, what the hell bombs do we carry?"

"None at all, so I do real important jobs like hold all these plates in place when we take off," and spreadeagled against a small table against a bulkhead he tried to keep cutlery from falling as we bounced on the rough ice, (in fact, he was a JATO or Jet Assisted Takeoff expert).

"Not another nut!" I said a little wearily, "Tie yourself down for Crissake!"

"Oh, old Hank knows what he is doing." said Rudy complacently fielding another stray plate. The engines thundered, we bounced and slewed when we hit drifts, and finally lifted a few hundred feet, and ten miles on, put down and taxied to within a hundred yards of the 'Nespelen' on the ice‑edge. Navy men ran out a 3in hose and we took on 32,000 lbs of fuel, and took off again at 11:30 and flew north about 300 miles to the David Glacier . No one but The Navy could have sent us on an expensive Trimetrogon photographic flight that day. The whole coast was socked in with low cloud! We glimpsed the crevassed ice of the David and the Drygalski Ice Tongue, turned back south and turned on the Trimet cameras. Orders were orders, so we took miles of luverly pictures of grey murk with occasional glimpses of black rock or dirty ice or bright snow. I sat in a plastic Observation bulge on the starboard side wearing a bonedome and headphones. It was nice and warm and Rudy handed out paper cups of coffee. It was the first time I had flown in a four engined machine aand it seemed enormous and compared to a Dakota purred along with remarkably little vibration. Today we would regard it as laughably small and the constant roar of the four unsilenced motors unbearable. An hour of little but cloud passed then red and black rock mountains showed. I flipped a switch.

"Hank, where are we?"

"You tell me and we'll both know, Bernie Boy!" came the cheerful reply. An Ice‑Tongue appeared, jutting out to sea, a floating glacier, with granitic rock‑walls not far to the north and south. Now there are only two big Ice‑Tongues along the Victoria coast, the Mawson and the MacKay. South of the tongue was a rounded black ice‑shorn rock dome, and at its foot and cut out of the living rock, a curious oval frozen lake with a tide crack running down the middle. It looked just like a hoof‑print! By God! Debenham, Gran, Forde and Taylor, 1911.

"Hank, Hank! We're right over Granite Harbour! See the Devil's Punch Bowl right below!"

"Right you are, Boy! Gotcha!" More cloud, which by the never‑failing irony of fate, hid the Dry Valleys which remained undiscovered for another year, as well as what was to be our 1957 sledging route inland up the MacKay Glacier, the snout of which we had just seen. Not until nearly opposite our starting point did the cloud give way to bright sun. The lower Ferrar was pocked with thaw channels and ablation debris and looked what it was, a rough road to travel near it's foot but further up it appeared like a smooth clear ribbon of ice and snow.

Butter Point, a suggested Base site, was all snow, and looked as though if the sea‑ice went out, it would be cut off from the Ferrar by about 4-5 miles of sea, though there was a series of gravel beaches along the southern shore, but the Ferrar Glacier on it's southern side was very broken and rough so that though one could walk along the beaches from Butter Point to the glacier front, it looked quite impossible that a road could be made for vehicles to get onto the smooth going a few miles up the glacier by that route.

The Blue Glacier comes through the coastal mountains to join the Piedmont Ice which forms a kind of coastal plain a few miles wide. It lies about a dozen miles further south but was also seamed by thaw channels, and while Armitage used it as a way into the Ferrar in 1902, it looked a hopelessly impractical route, as indeed it was, though in the Spring of '57 we were to sledge up it by keeping above the glacier on the snow‑covered slopes of the hills. The Blue is large Mountain Glacier draining the eastern face of the Royal Society Range. I took no notice of the "Snow Valley" in the upper reaches of the Blue Glacier, which lies along the foot of the main Royal Society Range, and was later to be a focus of interest.

The Koetlitz Glacier is famous in the literature for its chaos of thaw channels, moraine heaps and glacier tables and enters the bottom corner of McMurdo Sound from the south-west but it was obvious at once that it did not drain the Plateau Ice, as for some reason Taylor, Wright and Gran believed, but only the extreme south of the Royal Society Range near Mount Huggins and the northern slopes of Mount Morning. One problem crossed off, no route that as the mountains at it's head were all 5-6-7,000 ft or more!

"Captain to Observer!"

"Hi, Hank!"

"Come forward, will ya, Bernie Boy ? We have us a problem!" I leaned over the pilot's seats.

"That white stuff ahead," said Jorda, waving at the sunlit slopes of Mount Morning. "Is that more cloud or what?"

"It's 'What' with rocks in it."

"Hell you say! How do ya know?"

"For God's sake, you iggerant Swede, see the crevasses in it in those blue patches, and the black rocks over there! Of course its bloody mountain!" "I see," said Donovan polishing the windscreen with a black horse‑hide glove. "You can tell its snow by them little blue lines." By curious coincidence, an Air New Zealand passenger plane was later to fly into Erebus itself, only a few miles away, because the pilot could not tell snow from cloud by means of the "little blue lines".

We turned sharply east and passed north of the volcanic dome of Mt. Discovery and turned south again along the eastern slopes of Mt. Morning. We passed over the east rift zone of Mt Discovery, a twenty mile cleft marked by a chain of small cones, but it was on the other side of the plane and I did not get a good view. Half an hour later a great wide glacier enclosed between sheer rock walls appeared on our right, slicing straight through the mountains for about thirty miles, then widening with a series of feeder glaciers flowing in from higher land. In the far haze to the west seemed to be the Polar Plateau though dotted with black nunataks. The map on my knee merely showed a gap in which was scrawled "Skelton Inlet." I rapidly sketched in "Skelton Glacier!"

"Observer to Captain."

"Hi, Boy!"

"Nice big glacier to starboard, can we take a look?"

"OK, on our way back." The next gap was shown as 'Mulock Inlet'. Mountains rose steeply to about 10,000 feet on either side, but the Mulock Glacier was short, only about fifty miles long in total, and plunged directly from the Ice Cap onto the Ross Shelf. Though I photographed a narrow ledge of snow under the mountains on the north side, the greater part of the glacier was horribly broken and no possible route. Then came the relatively bare Darwin Mountains, but the Darwin looked icy and though only patches of crevasses, there was an icefall. Two years later one of our parties came down it by dog‑sledge and snowmobiles have operated on the lower reaches, but at the time I dismissed it completely.

In 1902, Scott, Wilson and Shackleton saw the mountains from the distance and the only book they had with them on that gruelling journey, was, Darwin's "Origin of Species"! Mounts Longstaff and Field drifted by.

"Hi, there, Boy!"

"Yup!"

"Big mountain coming up on starboard. What is?"

"Mount McClintock."

"OK." Half an hour passed.

"Hey, Bernie!"

"Uh-huh?"

"Big mountain off starboard beam. What is?"

"I told you, Mount McClintock!"

"No kidding! Looks different!"

"Of course it does, now we're looking back at it from the south‑east." "Oh!"

I perched out in my plastic bubble sketching and changing cameras frequently. It was cloudless and the white glare of the Ross Ice shelf extended south and east over the horizon. The never‑ending chain of the Victoria Land Mountains went on and on, damming back the ice of the Ice Cap, which at intervals of twenty to fifty miles had broken through, sending a vast river of ice, an Outlet Glacier, pouring down through the mountains to merge into the Ross Ice Shelf.

"Hi, Bernie!"

"Yo!"

"What the hell is that below? Looks like a rough sea!" My map had indicated a gap in the mountains entitled "Barne Inlet". A vast stream of ice cut straight through the mountains, the lower extremity having it's crevasses rounded and polished by wind and drift, and the surface did indeed look like waves on the sea.

"What the hell is that below? Looks like a rough sea!" My map had indicated a gap in the mountains entitled "Barne Inlet". A vast stream of ice cut straight through the mountains, the lower extremity having it's crevasses rounded and polished by wind and drift, and the surface did indeed look like waves on the sea.

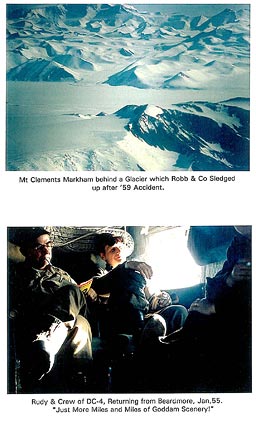

"It's the Barne Glacier, must be one of the biggest in the world, what is it, twenty miles wide and a hundred long? We are the first to ever see it!" "Lovely place for a walk! Big flat‑topped mountain coming up?" "Mount Albert Markham!"

"OK." Below the great mass of ice from the Barne forced the ice shelf away from the land in a chaos of enormous crevasses. Five years later I was almost to die in one of them and to see one of my good men buried in the snow. Perhaps it is as well we cannot see the future, even through a glass darkly. Michael Barne and Mulock made a little publicised journey in 1902‑3 and mapped in the Mulock and Barne region. They thought the passes through the mountains were straits or "inlets" as they were not close enough to see the immense flow of ice that passes down these gaps in the mountain chain. Now, sadly, the Barne Glacier has bee renamed the "Byrd" after Admiral Byrd, who never saw it either!

The mountains changed beyond the Barne, from being an apparently single range north of Albert Markham to no less than three ranges to the south, a block‑like coast range, a parallel valley, a tilted block range, then another snow valley with the massive main range behind. I sketched rapidly.

"Great big mountain ahead!"

"Mount Clements Markham. He was the old boy who got Scott appointed leader of the Discovery expedition!"

"Didn't do him much good, did it? 'Nother whacking great glacier below, God! Must be bigger than the last one!" The map showed "Shackleton Inlet" in about this position.

"That's the Shackleton," (Now renamed the "Nimrod Glacier"). "You should be able to see the Beardmore soon, see, beyond the little hill, that's Mount Hope."

"OK, think so!" Over the snout of the Beardmore, or rather where it vanished into the Ross Shelf, close to Mount Hope, near where Shackles lost his last pony down a crevasse, close to Shambles Camp, and where Scott lay for days trapped by a heavy fall of wet snow, near where Petty Officer Evans died, we turned off cameras, and swung back north, over the glare of the Ice Shelf on a course about a hundred miles east of the mountain ranges. I joined Jim Swedener and Rudy the Crew Chief, for a coffee. Rudy sprawled in a chair, reading a garish pulp magazine.

"You're no damned romantic, Rudy!"

"Howzzat?"

"We've just flown over a thousand miles of mountains no one has ever seen before and you read that stuff."

"Oh, nuts," said Rudy, waving a deprecating hand. "Just more miles and miles of more goddam scenery!".

Coffee‑break over I drifted forward to the flight deck.

"Are you really coming down again next year with the big expedition ?" asked Donovan. "Are you the Leader?"

"Oh, heavens no! I'm just the geologist, the Leader will be Sir Edmund Hillary".

"Well, you never know," chuckled Donovan. " You might find lots of gold or something and they'll knight you too, and then we poor pilots will have to tip our hats to you, "Good Day, Sir Bernard, How nice to see you, Sir Bernard!"" Rudy turned in his seat fingering his cap, while Donovan tugged a forelock!

"Well met, Sir Bernard, I hope you remember your poor friends!" I collapsed, giggling in helpless fashion.

"Stow it, you clowns", I said at last. "Are we going to make a pass up the Skelton Inlet?

"Just as you say, Sir Bernard",

and Jorda stretched forth a hand moving a knob slightly and the great machine banked to port, the four engines rumbling louder, and we turned north‑west towards the distant gap in the mountains where the wide gently sloping glacier had appeared on our southern flight. It was my first experience of an automatic pilot and I was suitably impressed.

The lower thirty miles or so of the Skelton Glacier were completely level and lay between facetted rock spurs. Later we were to find that it is in fact afloat in a deep fiord which I guessed to be 6 to 10 miles wide. A massive mountain group to the south culminated in an attractively rounded peak of 10,000 ft. called Mt Harmsworth (which a year later we climbed), then to the north lay a jagged rock peak we later named "Tricouni". To the north of it was the southernmost peak of the Royal Society Range, Mt. Huggins, about 12,000 ft in height which could be seen from McMurdo, and which we climbed in 1958.

The lower thirty miles or so of the Skelton Glacier were completely level and lay between facetted rock spurs. Later we were to find that it is in fact afloat in a deep fiord which I guessed to be 6 to 10 miles wide. A massive mountain group to the south culminated in an attractively rounded peak of 10,000 ft. called Mt Harmsworth (which a year later we climbed), then to the north lay a jagged rock peak we later named "Tricouni". To the north of it was the southernmost peak of the Royal Society Range, Mt. Huggins, about 12,000 ft in height which could be seen from McMurdo, and which we climbed in 1958.

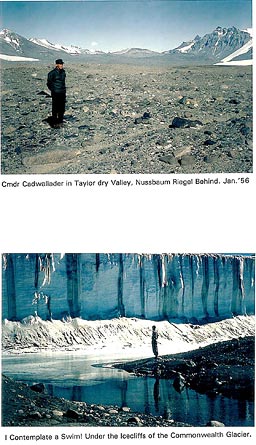

The north arm of the glacier curved towards Huggins between some rock nunataks and then up a couple of minor steps, (later called the Lower and Upper Staircase) and seemed to partly drain a great broad basin ringed in by a line of nunataks, but imperceptible passes led to the great continental ice‑cap and it seemed some of the continental ice also passed down into the Skelton. There were odd crevasses but it obviously gave relatively easy access to the Polar Plateau, something which none of the other glaciers we had seen did. It still is the only glacier by which vehicles have ever ascended from the Ross Ice Shelf to the Ice Cap. We did a lazy four hundred degree turn to Port and came back along the face of the glaciated mountains which lie behind the Royal Society Range, which had also never before been seen.

"Seen enough?" asked Rudy and I nodded, taking a deep breath. It seemed to good to be true, I been told to look for a way through the mountains, and it seemed we had found one. We passed over the mountains near Tricouni and dropped down the pock‑marked Koetlitz. Back at McMurdo we landed on the sea‑ice beside the ships, more than a little elated. Possibly no human beings have ever seen so much virgin mountain territory in a single day before in the whole of history and certainly none have since. True, Scott, Shackleton and Wilson had seen the summits of much of the main range from a distance but they had been too far distant to see the glaciers, though they saw the gaps and recorded them as "Inlets". The irony of the cloud covering the area south of Granite Harbour to the Ferrar was not apparent till more than a year later, as it concealed the "Dry Valley" area, the discovery of which was to involve a great deal of stress and travail. "Tonight we dine in style!" said Jorda cheerfully, shaking out a virtually uncreased uniform from hanging lockers aboard the Skymaster. Like visitors to a new town, we left the plane together and headed for the ice‑edge where by now no less than three Ice‑breakers and four cargo‑ships were tied up.

"Let's try that one over there, the biggest should have the best restaurants!" I began to have doubts, it was all in order for to American officers to walk aboard a strange ship as though they owned it, but I was just a passing Kiwi! We climbed a gangway and passed through a steel door into the usual heat and smells. A seaman approached as we stripped off parkas.

"Take us to the Officer's Country!", snapped Jorda with a new note in his voice.

"Yes, Commander! If the Commander will come this way... !" I stared. My little old, slightly comical, friend was revealed in immaculate dark serge uniform with the three gold bars of a Commander on his sleeve. The seaman opened the door to positively luxurious officers mess, brilliantly lit, with gold braid everywhere, vastly different to our simple old icebreaker.

"Hank, Hank, I don't know if I really should.... !"

"Bernie Boy," said Jorda kindly. "You are our guest. Also you are one dam' good observer and we owe you one. And forget about whether you 'should ', I outrank everybody on this dam' barge!"

And eat in style we surely did! I even had a shower!

©2007 - may not be reproduced without permission