11 – The Skelton Geological Party

Four huts were now up by the 26th Jan.56, and the ship virtually unloaded, though out at the base‑site everyone still slept in trail tents. Up the hill a ways Neil Sandford and Mulgrew were raising a mighty antenna field with the help of the half‑track and a winch and kept going on about "Dipoles " and "rhombic patterns".

Four huts were now up by the 26th Jan.56, and the ship virtually unloaded, though out at the base‑site everyone still slept in trail tents. Up the hill a ways Neil Sandford and Mulgrew were raising a mighty antenna field with the help of the half‑track and a winch and kept going on about "Dipoles " and "rhombic patterns".

I brought in a load of Bluejackets from the ship to work on the site and filled in time jack‑hammering permafrost for the Scientific Hut foundations, in a weird mixtures of scoria, basalt and ice wedges. About a dozen seamen, distinctive in blue britches and seaman's jerseys, toiled on pick and shovel.

"Must be quite a change for you, Shorty," said I cheerfully to the Buffer who leaned on the other side of the clattering hammer.

"Wot the 'ell d'yer mean?"

"Well, after all that time on the soddin' sea, must be great to be able to look back on the time you once built a base in the Antarctic. Must be fun!"

"Fun do yer bloody call it? D'yer know wot them bloody Satidy‑night sailors are doin' back aboard right nah? Kippin' it aht, that's wot, eighteen hours a bleedin' day in the sack, while we do graft aht 'ere. Bleedin' 'ell!"

"What the devil is a "Saturday‑night Sailor"?" I asked Mulgrew next time he came alongside.

"Naval Reserve," he grinned, "The permanent Navy hate 'em." It takes all sorts!

Sir Ed, without warning suddenly relented saying I might as well fly out to the Skelton with Guyon Warren and Arnold Heine and do some geology. How about some dogs ? Weren't any, manhaul. How long ? Oh, a couple of weeks! How about George's team ? Bob Miller and Roy Carlyon were going to use them to sledge out the route from Base to the Skelton. Oh?

I had to admit, it did make sense, it would take ten days or so to sledge out, over snow and ice a few thousand feet thick. Though one skirts the volcanic White Id., and Minna Bluff, close to both the ice is notoriously crevassed and even these volcanic piles cannot be approached from that side.

Hum! All this construction was quite fun but not what we were here for, more a necessary evil.

I sounded out my two prospective partners. Arnold Heine was and is a bit hard to describe, a natural all‑rounder, a born back‑country tramper, shooter, skier and something of a climber, he held some indefinable position in D.S.I.R, mostly on environmental projects. He was down for the summer only, heaven knows as what, but he was to return to the Antarctic many times usually in the guise of "Field Assistant" or "Glaciologist".

Guyon Warren was a serious young geologist, quiet and reserved and though he at times seemed to lack the drive and fire of some of our more flamboyant members, yet he never held back and seemed to have an infinite depth of courage. Oddly enough, we proved to be a congenial enough group, though three more different people could hardly be put in one tent.

Sledging rations made up in convenient ten‑day‑for‑two‑men boxes were in short supply due to losses in the flooded hold of the ship and we tossed together a heap of heavy canned goods, though a Depot had already been flown out to the Lower Skelton. We had a couple of sleds, a wooden Nansen and a fibreglass banana boat, geological hammers, brunton compasses, maps, field books, skis, crampons, iceaxes, climbing ropes, tents, a cook box, the pile grew. Nevertheless, having read quite widely on Antarctic exploration parties, I doubt any group had ever before set forth so casually and with so little planning.

No Beaver for us, Cranfield was to fly us out in the little Auster, which, now on skis, had rarely been used. With all its radio gear aboard, only one passenger could be carried, and not only the sleds but also the tents had to be lashed under the wings or under the fuselage. Under Antarctic conditions it was a useless aircraft, with less load capacity than the Fox Moth used by Gino Watkins and Hampton in Greenland and on Rymill's "Penola" expedition in the thirties, actually it had the same Gipsy Major engine.

The whole Saturday was taken up with Cranfield making two trips with gear and the other two men. I filled in time with shovel and broom clearing out the completed C hut which the builders had left in the usual mess. Cranfield returned late in the evening and had done enough flying for one day, so I unrolled my bag on an airmattress on one of the new bare bunks in C hut, being the first person to sleep in it.

Landing at Skelton Glacier after an hour and a half flight we found a tent in the middle of a vast snow plain at the entrance to a ten‑mile wide fiord with mountains rising to ten thousand feet only 15 miles to the west. The scale seemed enormously greater than it had ever seemed from the air a year before, and pausing only to wave the Auster off and fit a sledge‑meter wheel to the Nansen, we set off for a low dark bluff a mile or two to the south. "You have to realise, chaps," said I as we strode over the glistening snow, "that appearances are bloody deceptive. Now that old Teall Island ahead may look half a mile away, but I bet its nearer two!"

"Or four!" I added an hour later. Teall Island was a bare island of rock, a couple of miles long and about 500 feet high. Bedding showed up plainly, it had to be sedimentary, and excitement grew as we closed with it. We crossed a shear zone at the edge of the ice, with an undoubted step up, our perishing glacier was afloat! One can't mistake a tide‑crack even if we were a hundred miles from open water.

It was the first step onto solid rock for our expedition on the Antarctic main, as while Bob Miller and I had landed at Butter Point, it was only on moraines. It is a strange feeling to mar the pristine rock, blasted for centuries by the blizzard, but never disarrayed by the foot of man or dog. For both Warren and I, it was a home‑coming, we stared down at common old greywacke, so similar to the eastern Southern Alps that we both knew well. It had more carbonate in it, being laid down in a continental environment, but the folds, quartz lenses and shining micas were so familiar. Snow is all very well in its place, but here was good old terra‑firma, with natural handholds and ledges created especially for human hand and foot, and we ran about like children. Then we got serious and sketched folds, photographed, sampled, and finally skiied back to our tent way, way out on the snow‑plain.

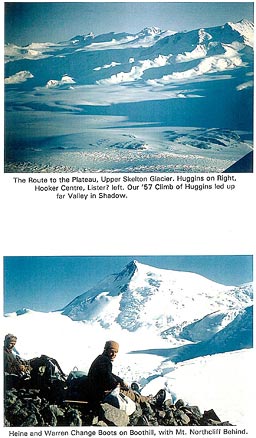

As the Skelton seemed to be at least ten miles wide, we decided on traversing up the south bank and returning along the north bank, which seemed to have less rock out‑crops, the south side looking much steeper with a quite grand mountain rising to ten thousand feet with the not very harmonious name of Mount Harmsworth. This had been seen from a great distance by Scott, Wilson and Shackleton in 1902 and named after Lord Northcliffe, Earl of Harmsworth who backed the "Discovery" expedition. To anticipate a little, we found a large glacier flowing over imposing icefalls from the eastern slopes of the mountain into the Skelton, so it seemed apt to name it the "Northcliffe Glacier" and another mountain at its head, "Mount Northcliffe" so the gentleman, at the expense of golden guineas, became better commemorated in the distant south than ever he was to be through his newspapers in far off London.

As the Skelton seemed to be at least ten miles wide, we decided on traversing up the south bank and returning along the north bank, which seemed to have less rock out‑crops, the south side looking much steeper with a quite grand mountain rising to ten thousand feet with the not very harmonious name of Mount Harmsworth. This had been seen from a great distance by Scott, Wilson and Shackleton in 1902 and named after Lord Northcliffe, Earl of Harmsworth who backed the "Discovery" expedition. To anticipate a little, we found a large glacier flowing over imposing icefalls from the eastern slopes of the mountain into the Skelton, so it seemed apt to name it the "Northcliffe Glacier" and another mountain at its head, "Mount Northcliffe" so the gentleman, at the expense of golden guineas, became better commemorated in the distant south than ever he was to be through his newspapers in far off London.

After a long sleep, the sleds were packed and we laid out man‑hauling traces on the snow, looking at them in no great admiration. A wide canvas belt was supported by a loop round the neck but remembering that the invention of the horse collar in about Elizabethan times doubled the efficiency of the horse, it seemed a pity no such thought had gone into making man a better draught animal. The sun shone fitfully through the cloud, the sleds squeaked over low sastrugi and we made abysmally slow progress, less than three miles an hour. Boring, very! At long, long last we neared a great barefaced bluff guarded well by crevasses, through which we threaded, dropped harness and approached vertical walls of a lovely dark crystalline granodiorite. This is a massive intrusive rock, forced up into crust, and which had crystallised so slowly that crystals of hornblende and micas were up to an inch long. Dark green copper stains attracted our attention, but they came from tiny copper‑pyrite grains, not from any interesting ore.

Skirting another tributary glacier that we named heaven now knows what, we found more crevasses, usually only a foot or two wide. Suddenly Heine stopped and cocked an ear, a distinct buzzing could be heard from out over the Skelton.

"Hark?" cried he, "Do I hear angels?" Unfortunately, he chose to step backwards at the same time, broke through a thin snow‑bridge and shot down into the depths to his shoulders. When we could control the unseemly mirth we helped him out.

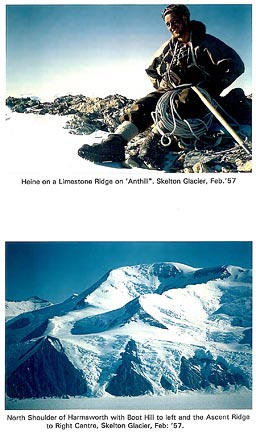

"You nearly heard angels all right!" was the general tenor of remark for some time. We camped under a great layered sloping ridge leading to a 3000‑foot peak we dubbed "Anthill" for reasons not well remembered. The next day we kicked and hammered at Anthill for some time before deciding the whole thing was a formation of bedded limestone and marble. Further west, across the Northcliffe Glacier rose the massive glaciated summit of Mt Harmsworth, or so we thought. We stood on the bare yellow rocks and gazed.

"What d'y' think, boys"? said I, finally.

"That ridge will go," said Guyon pointing with iceaxe to a winding ice and rock rib, studded with gendarmes that led away from us, from a steep three thousand‑foot deltoid bluff that rose above the Skelton.

"Or sidle the glacier to that col further south," said Heine.

Back at camp, the tent sagged in the warm sun. There was a whine in the sky:

"Wake up, you lazy sods!" cried a voice, a heavy bundle of mail struck the tent door, and there was a shattering roar as the Gipsy Major opened up and the Auster climbed away. Cranfield always preferred the sneak attack.

©2007 - may not be reproduced without permission