7 – The Voyage of the "Endeavour" ex "John Biscoe"

I went below while the Dog Island light was still abeam and turned into the usual chain rack, the lowest of three, accommodation being even more crowded than the old "Edisto" had been. It was back to the old roll, pitch, rumble, stagger again, motor‑ships are hell, if the Good Lord intended man to motor He would never have put oil so far below ground and made wind free. It took a few days to settle down and I remember perching on top of dog crates on the foredeck in the chill sun and a heaving sea watering dogs while Ellis passed me the bowls, looking disgustingly cheerful.

I went below while the Dog Island light was still abeam and turned into the usual chain rack, the lowest of three, accommodation being even more crowded than the old "Edisto" had been. It was back to the old roll, pitch, rumble, stagger again, motor‑ships are hell, if the Good Lord intended man to motor He would never have put oil so far below ground and made wind free. It took a few days to settle down and I remember perching on top of dog crates on the foredeck in the chill sun and a heaving sea watering dogs while Ellis passed me the bowls, looking disgustingly cheerful.

There was no using the fathometer for further work on the Indo‑Pacific Rise, this was an R.N. ship and no‑one was allowed on the bridge except watch officers and helmsman! The result was that virtually no new knowledge was gained in a rarely traversed ocean. I tried to interest various people in the fact that somewhere below us was one of the biggest seamounts ever which brought forth various sarcasms to effect we were going to cross Antarctica, not submarine hills. Somewhere in the furious fifties we ran into a gale, dog kennels on the foredeck were smashed and Richard and I stood by the starboard scuttle as George made dashes to the foredeck between breaking seas to return with a dripping husky. We would slam the scuttle shut as George leapt the transom to safety and the next wave roared down the deck.

"Missed me, you Bastard!" George would shout dramatically, and prepare for another sortie. Soon dog howls were being heard from every cabin and alleyway.

"You've got a wolf or two in there George!" we would say after a particularly long and drawn‑out effort. Marsh would pretend to listen intently and then smile in relief,

"Not one of mine, must be yours, Richard." Then the Tannoy would crackle,

"Would some Expedition member kindly repair to the Captain's Cabin and remove this animal!"

Richard and I shinned up onto the Monkey Island above the bridge. The wind was blowing sixty knots and the sea was streaked white with the crests half a mile apart. The "Endeavour" would dip her bows under and the sea would wash along the deck until only the bridge was clear above the water and the ship would wallow and stagger drunkenly like a surfacing submarine. Then the Jackstaff on the bow would appear above the seas, then the top of the Beaver crate lashed on the foredeck, and finally hundreds of tons of water would cascade through the freeing ports and over the bulwarks and finally we would emerge for as long as we remained on a crest. Sleep was difficult and Mulgrew rigged a hammock in the Expedition Mess but for the rest of us it was a case of "Hang on, Jack!" in bunk or out of it.

When the weather moderated, we spent spare moments checking field gear, sewing lampwick onto mitts, nose protectors on to goggles, or special strips of wolverine fur onto anoraks. Just before leaving I had received the set of aerial photographs promised by Trigger Hawks taken during his 'Highjump ' flights in 1952 and I pored over these in some excitement. One run taken along the face of the Barrier, ended in a pass around the face of the mighty Royal Society Range west of McMurdo Sound. The second‑last photo showed the barren Taylor valley and the last photo of all, taken on an extremely oblique angle from a distance of twenty miles as the plane swung back east, showed the range to the north of the Taylor and part of the next valley, the one I had labelled "Wright Glacier " the year before.

What the photograph showed was a level floor covered in gravel and old moraine! While not the whole width of the valley floor appeared, it just had to be another 'Dry Valley' like the famous Taylor, until then thought to be the only large ice‑free valley in the whole of Antarctica.

With hands just shaking slightly, I took it to Sir Ed.

"Really?" said he, indifferently, "So what's so special about Dry Valleys?" When one is supposed to be exploring one of the five main continents and it just been suggested that the area of ice‑free land is twice as great as previously supposed, it had seemed to be so obviously important, I didn't have a very convincing story ready. I rambled on a bit about how the main discoveries of 'Highjump' had been a few acres of bare land named "Bunger's Oasis", but Sir Ed obviously was bored with the whole conversation.

I lay in a bunk and cogitated. If the Wright Valley as well as the Taylor was Ice‑free as well as parts of valleys near the Koetlitz Glacier, then we had an area of about 500 square miles of bare land, not necessarily bare rock as glaciers leave a great deal of litter behind, all lovely and fresh, but miles from where they ought to be. Ultimately it turned out that there was about 2000 square miles of snow‑free country, now the best known area of the whole continent. I had put down twenty hours of aerial reconnaissance flying on my estimates and it was already obvious how it was going to be spent! I did not stop to think that Sir E's obvious indifference might make it very difficult to claim those hours!

We sighted our first ice, a lone growler at 11:30 pm on the 26th, and soon after, Scott Island, a solitary needle of an island, an almost replica of the Solander in Foveaux Strait. I made the routine request for a boat to land as Scott Island had only been landed on once previously, and received the routine refusal. Ship's captains always look on these activities as totally frivolous. Exactly where this lonely relic of volcanism fitted in to the total scheme was to plague us for years.

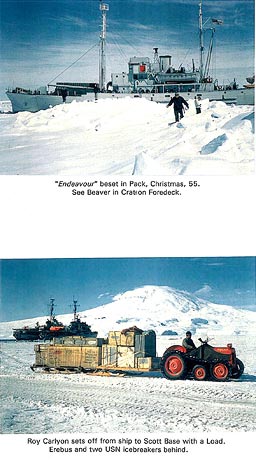

The two frigates, "Pukeko" and "Hawea" which had for some unfathomable reason, kept station with us so far, hooted dismally and dropped their speed to a crawl through the oppressive fog and bergy bits. There was a last exchange of mail, and they departed with exchanges of cheers and all that good traditional stuff. We entered open pack with calm seas, Antarctic petrels, humpback whales and crab‑eater seals and we were into the Antarctic at last. On Friday the 28th Dec. Jim Bates and I began running up some of tractors on the deck. One had a dead flat battery and with weary premonition,I hauled it out for recharging, the beginning of a never‑ending battle to keep internal‑combustion engines running under conditions that neither God nor man intended they should.

The ship finally came to rest in heavy pack and I stepped over the side for a picture of our beset ship, thinking naively that ice thick enough to stop a ship was also thick enough for man to walk on. It actually consisted of ten feet of sludge and as I backed away, eye to viewfinder, with a sigh it parted and I descended into water at 28 deg, Fahrenheit. By Joe! I tell you, that water was cold! No wonder most men die in water of that temperature in a few minutes.

As I tried to wriggle out, Bob Miller came to my rescue and also put a leg through. I threw him the camera, and seal‑like, emerged. At least the ship floated! We drifted all night with a half knot set to the north, and next day engines were started and we made another 70 miles through 7/10 to 9/10 pack, and then came to a stop again.

The next day was officially declared Christmas day, apparently Sir Ed having authority to fiddle the calendar a little, it now being nearly New Year, but a gale in the Furious Fifties is no time to celebrate anything requiring overeating!

As my diary relates: "Christmas dinner began with asparagus soup, chicken, roast spud, cauliflowers (overdone), followed by strawberries, both hock and claret being circulated freely. George Marsh was at his witty best and the conversation, spurred on by the feeling that now the Expedition was seriously underway, fairly sparkled. There were several toasts and I rose to propose "Sweethearts and Wives " with a particular one in mind. There were the usual matelot cries of "may they never meet" and Ellis burst into "For They are Jolly Good Fellows" and then there was no stopping the songs, with voices more powerful than tuneful! To get your male Kiwi in a vocal mood, lubricate him well first! Ellis also led 'On Ilkley Moor bart 'at' which was rather well done, with the ship's Naval Officers standing at the wardroom door, joining in. After that came "Rule Britannia", after which all Naval Officers including Mulgrew, were scragged. Brookes led off an odd action song called "My Hat, it has Three Corners", but a group surrounded Mulgrew, who had become a bit too prominent, and used the actions to administer a sound thumping. At that point the usual moron tossed in a football and a fearful melee ensued resulting in the total wrecking of the Wardroom, culminating in Our Leader, in a gallant effort to score a try under the starboard bulkhead, going down fighting under a mountain of fourteen‑stone bodies." Keeping fit young men confined for even a week or two has its problems!" I kept well clear of the whole exercise, rucking under mess‑room tables not being my thing, but only a few blood smears seemed to result. The crew of the "Terra Nova" reportedly had a similar physical outlet after dining well, called "Furl t'galln s'ls", which mainly consisted of ripping each others shirts off!

The next day (30th Dec) we manhandled aboard two tons of ice to top up water tanks, and we pressed forward a few miles but at midday we came to rest again, the Captain announcing that we would wait "for the pack to loosen up a little!" We were all getting impatient with this lackadaisical approach, it was already past midsummer and we had a base to build. When either the Number One, or Brooke had the watch, they kept working at the ice, but now the Captain refused to let any other officer have the bridge. At least eight of us had been in ice before and were well aware of the need to keep working away at the pack. In the Weddell Sea the summer before, Sir E with his usual restless energy had found they could keep "Theron" moving by levering and poling lumps of ice away from the ship's sides, and there were murmurings from the ranks!

Sir Ed, never a patient man, wearing a grim expression that boded ill for someone, set off for the bridge, muttering in passing about "getting something damn‑well moving!" From the sound of raised voice that could be heard at the fantail, it was quite a row! From what we pieced together afterwards, Hillary pointed out the passing time and the need for action. The Captain, probably not used to having his actions questioned, became very brusque and claimed that the "Endeavour" ex "John Biscoe" had never before been in such heavy pack, that manoeuvring might damage the rudder, that both Smith and Brookes were too inexperienced to be relied on !!, that people who had spent one summer in the Weddell Sea, didn't know ice from bloody chocolate pudding!

Sir Ed, never a patient man, wearing a grim expression that boded ill for someone, set off for the bridge, muttering in passing about "getting something damn‑well moving!" From the sound of raised voice that could be heard at the fantail, it was quite a row! From what we pieced together afterwards, Hillary pointed out the passing time and the need for action. The Captain, probably not used to having his actions questioned, became very brusque and claimed that the "Endeavour" ex "John Biscoe" had never before been in such heavy pack, that manoeuvring might damage the rudder, that both Smith and Brookes were too inexperienced to be relied on !!, that people who had spent one summer in the Weddell Sea, didn't know ice from bloody chocolate pudding!

It was the old story of conflict between the Expedition Leader and Ship‑master. Shackleton was once so exasperated at the over‑caution of his Captain, he pushed him aside on the bridge of the "Nimrod" and rang down for "Full Speed". The Captain immediately rang "Stop"! On another occasion when his captain delayed unloading at Cape Royds yet again, Shackles was seen to tear off his cap and jump on it!

The reaction of Sir Ed was more to the point. He observed cuttingly that the ship might as well lose a rudder as drift around the Ross Sea all summer, and Sir Ed, not being renowned for mincing words probably put this quite plainly. The result was an incredible outburst of rage on the part of the Captain. Shouting, "If that's what you want, its what you'll bloody get!" he rushed for the telegraphs and rang "Full Speed".

With her vertical bows "Endeavour" took some fearful blows as we struck hard ice about 4 feet thick head‑on and we expected at any moment to have the diesel engines tear out of their beds and crash through the engine‑room bulkhead and into the ward room. At one point we were careering down a curving lead and struck a projecting ram aft the starboard bow. We were flung off our feet and piled in a heap against the hull, some of us sprang for the deck, but others more experienced, including Brooke and Mulgrew who had served on submarines, snatched up tools and timber and rushed below, expecting to find a flood of water, but the old ship, thanks to her greenheart sheathing, survived.

On the voyage out from England, most of our sledging ration boxes had been badly damaged by seawater being allowed to remain in the hold, after the storm in the Bay of Biscay and the Captain when challenged, had been ill‑advised enough to retort, "What do you expect? They're only made of plywood!" From now on, he was to be known in some contempt as "Our Captain Plywood!"

In the First Dog, Jimmy The One took over, and handled the ship as she should have been, "Easy Astern, Half Ahead " continually forcing our way through the floes, whatever his many and excessive faults, Smith, Lt Cmdr, RN, knew how to handle a ship. Brookes remained all night in the Crow's Nest, directing us towards leads, as the low sun warmed the deck and it appeared we might not sink after all. However, the Captain took over in the Graveyard watch and we resumed our insane barging. At one point I heard Richard aloft, report an open lead two cables west but the Captain ignored it and we charged on through solid ice. It was an odd experience to see a man doing his level best to sink a ship out of temper, and looking back, it is even odder we did not simply remove him from command. However, a Captain has absolute power at sea, and the lower deck might have felt duty‑bound to support the Captain.

I went below to debate the matter with George Marsh who, possibly coincidentally, was sitting in his cabin squinting up the barrel of a pistol. "I don't think the man is fit to be in command, George," said I. "What do you think?"

"He's quite bloody mad!" George agreed clinically. "Almost certainly the effects of all those sojourns in B.A. on the way to the F.I.D.S. bases. However, mutiny, old boy! Mutiny! Now if the ship starts sinking I suppose we'll have to do something!" He winced as the ship shuddered to another mighty blow on the bow, and began tapping .38 shells into the gun in an abstracted way, so I departed, my hopes of a bit of action involving rushing the Bridge, fading. That same pistol, incidentally, had rather defective ammunition. George once shot at a seal but there came merely a "click". A few seconds later it went off, missing George's foot by inches!

By 9 pm a swell announced the imminent arrival of open sea, and we broke out into the Ross Sea at 3 am on New Years day, and our problems were temporarily over, though we were rolling 48 degrees. Several of the American ships were ahead of us and it should have been simple to join them in McMurdo Sound. We approached Beaufort Island which lies a few miles north of Ross Island, and the "Glacier" advised us by radio to stand well to the northwest to avoid heavy ice. Whether out of vindictiveness or no we were never to know, but our Captain steered straight into the pack between Beaufort Island and Cape Bird. It was old bay ice, about ten feet thick and hard as iron. Bates and I stood at the fantail, staring out our wake, which was absolutely littered with broken timber.

"Now where in hell is that little lot coming from?" said I. We went forward and leaned over the bow, where long lengths of timber about 4 x 2 in size were being flung out, as though from a porthole. We leaned further. It was our Greenheart sheathing, which was only spiked onto the hull, being stripped from the bow by the hard ice! I ran for the bridge companion.

"Get to hell off the bridge!" roared our Captain Plywood.

"All our greenheart is being stripped off!" I panted. The following exchange accomplished little and is better forgotten, though I am told that the invective, which could be heard from way aft, was unusually original. However, when i though about it, I decided that that was the last time any uniformed lout was going to get away with being abusive and that any repetition would earn the offender a swim toute de suite and moreover, free. This well-meant resolution was to have an amusing effect later in a Canadian icebreaker when I charged the bridge to administer the swimming rites to find the offender was a female officer.

We continued to forge slowly ahead getting lighter every minute, finally becoming totally beset. A few hours later "Glacier" came to our help, all ten engines roaring, and tossing aside floes like confetti. With a brief "Follow me!" on the loud hailer, she turned and led us back the way we came in, north about Beaufort Island into the open water we should have followed in the first place.

Our Navy contingent squirmed, red‑faced. For even so insignificant a member of the RN (The Real Navy) to be rescued by the American so‑called Navy was too much to be borne, and much of this resentment was focused towards the Captain. Smith especially, who hated unseamanlike behaviour with a hatred and intensity not often seen, was in a particularly murderous mood.

"Glacier" punched us out a small bay in the fast ice in the middle of McMurdo Sound opposite Cape Royds, and our mooring lines were run out, and we came to rest at last. Remembering that our Number One, cutlass in hand, once threw a gauntlet at the feet of the Captain of the battleship "Duke of York" and challenged him to a duel (being flung arse over tip over the rail back onto his submarine for his pains), it was really quite surprising that the voyage had been so uneventful.

©2007 - may not be reproduced without permission