Preface

Life, as some medieval philosopher once pointed out, consists of an infinite series of cross‑roads. If one takes this too seriously of course, one is likely to remain frozen in one's chair, rigid in the realisation that the choice of either continuing to read a book, or going to the gate to collect the milk, represents an irretrievable dichotomy in one's life, the future will irrevocably diverge and one's whole future will never be the same. The awful responsibility for such a no‑longer simple decision is enough at times to keep one frozen immobile, the alternative paths leading to the future being less than adequately sign‑posted.

Life, as some medieval philosopher once pointed out, consists of an infinite series of cross‑roads. If one takes this too seriously of course, one is likely to remain frozen in one's chair, rigid in the realisation that the choice of either continuing to read a book, or going to the gate to collect the milk, represents an irretrievable dichotomy in one's life, the future will irrevocably diverge and one's whole future will never be the same. The awful responsibility for such a no‑longer simple decision is enough at times to keep one frozen immobile, the alternative paths leading to the future being less than adequately sign‑posted.

Marcus Aurelius long ago gave his advice, one can only soldier on in modest hope and in the knowledge that inevitably we too will rest in our domus terminus, but as one looks back over past years, isn't it appalling how lightly we once decided to follow some course which led only to toil, desolation and death?

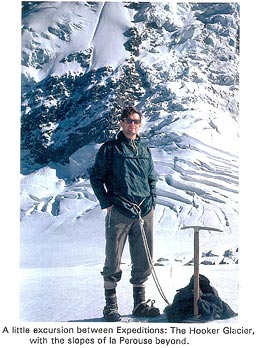

One of those light‑hearted decisions which made me for some years a polar explorer of sorts rather than merely a desk‑bound academic took place appropriately enough, in a mountain refuge called Pioneer Hut, high in the Southern Alps. I had almost completed a Masters degree in geology on the structure of the Alps and their glaciers, while at Otago University. A series of improbable meetings and chances had resulted in joining Professor Arnold Lillie of Auckland, a structural geologist of the Swiss School, in an expedition high in the Alps, and he brought with him, after another improbable series of coincidences, an Oxford geography graduate called Andrew Packard.

Taking advantage of our surroundings and the weather, the day before we had ascended the great ice pyramid of Lendenfeldt, and then I with another member, Peter Robinson of Dartmouth College, went on to the summit of Mount Tasman. Robinson, being a keen mountaineer and having landed in New Zealand less than a week before was suitably impressed with our Queen of the Alps and her pristine approaches.

The next day the blizzard blew, but we lay in the tiny rocking refuge of the old Pioneer Hut (before it was destroyed by a rockfall) and Robinson regaled us with stories of the Bugaboo Range in British Columbia. Packard in his turn confessed to coming to New Zealand on the trail of a single forlorn ambition, to join an Antarctic expedition which was rumoured to be in the offing.

"But it's no use," he concluded gloomily. "They aren't interested in mere geographers. You know," suddenly turning to me, "You should go, they want a geologist, and you are at home in all this," (waving at the surrounding bleakness of snow). "They want someone to go down this year with the Americans, why don't you apply?"

I reflected a little on this as the single candle flickered in the blasts of wind and the others retreated into acrimonious argument as to which of the great pile of classics Packard had carried in, could be read by whom.

It was 1955, ten years after The Bomb which had ended the war so precipitately and amputated my ambitions in the Air Force flying world. The motor car was destroying distance, remoteness and privacy, the old familiar smells of horses and saddle leather were fast going, there was scarcely a hitching rail to be found in even a country town any more. No longer could one take a pack‑horse and a few supplies and wander off into remote and unspoiled country, even at the foot of the glaciers where we now were, there were tourist hotels and it was rumoured that Harry Wigley of Mount Cook Hermitage, had developed a plane with skis that would soon be bringing tourists even up here. Before the war, one could take a rifle and wander for weeks amid the mountains amid rivers, forest and deer, never seeing the depredations of man, but all this was going fast. The Antarctic did not sound overly attractive: I had read the stories by Scott and Apsley Cherry‑Garrard, of long winters in total darkness and cold, lit only by flickering aurora and diabolical flames of evil volcanoes named, appropriately, Erebus and Terror.

All the heroes seemed to have died appalling deaths by scurvy, starvation and exhaustion, but on the positive side, Antarctica was a whole continent the interior of which was shown on maps merely as a blank and for the last million years or so all young men have had a yearning to tread where no other has been.

New Zealand was already settled, old and staid; people fussed about their lawns, carpets and pet cats, it was fast becoming a wonderful country for women and geriatrics, but not so entrancing to one only 27 years old. The conclusion after all this mental debate was that if I went down the following summer and found it too bleak, diabolical and boring, well, I was not committed to return and could go off to India and the Himalayas or to Africa and shoot rhino or find some similar, more interesting activity.

Some weeks after returning to civilisation, if that is not praising the city of Dunedin too highly, I wrote to the address supplied by Packard of the Ross Sea Committee as it was called and in short order was asked to attend a selection group of the Ross Sea Committee in Christchurch, to which city I duly repaired. I waited upon a group of gentlemen entirely unknown to me except for one Earl Riddiford, a Wellington lawyer, with whom relations were just a little touchy as we had recently pipped him on a virgin face climb on Mt Malte Brun , as a result of which he was not overly warm in his greetings.

The conversation was quite desultory until suddenly a door was flung open and in loped a tall, loose‑jointed figure, none other than Sir Edmund Hillary himself, fresh from his exploits on Everest and now to be the leader of a New Zealand party to cooperate with a British party who were to attempt to cross from the Weddell Sea to the Ross Sea, right across the whole continent, or so I was now told. He flung himself in a chair opposite and the rest of the panel grouped themselves sedately behind and I was amused a little at the way he dominated the whole room. He fired off questions as to my background, seemingly much more interested in my two summers as student Guide with Harry Ayres of Franz Josef Glacier, than in my poor, slighted, science degree.

A few weeks later I was told to proceed to the port of Lyttleton in early November, 1955 and report on board an American naval icebreaker, the "Edisto" for three months in Antarctica. I was to locate a suitable site for a base for the New Zealand party the following year, I was to find a route suitable for vehicles through the Victoria Land mountains up onto the polar plateau, as Scott's old route up the Beardmore was obviously quite impassable being extremely hazardous even on foot. I was to observe American methods of polar building construction and, it seemed, act as general spy on What The Americans Were Up To!

Quite how I was to explore a sizable chunk of the continent on my own was not revealed, but it was suggested I might be able to persuade the Americans to lend me an aeroplane or two! Two glaciers flowing into McMurdo Sound, the Ferrar and Koetlitz Glaciers, were mentioned as possible vehicle routes and a place called Butter Point near the seaward end of the Ferrar as a possible base site.

Hillary and two others were to go to England and join the ice‑strengthened ship, the "Theron" for a summer voyage to the Weddell Sea with the British party, and old friend Harry Ayres was to go the Australian base, Mawson, with an Australian ship and bring back some dogs. It sounded very complicated and rather like being back in The War.

There were to be two other New Zealanders also visiting McMurdo Sound that year, a Dr Trevor Hatherton, a DSIR geophysicist who was to be Chief Scientist at the new Base for the coming International Geophysical Year, on a larger naval icebreaker, the "Glacier", and a certain Lt.Cmdr. Smith who was "To Observe the Movements of Shipping!"

In the meantime I had to have a Medical Examination! Bureaucrats are very fond of these and the stories were still fresh in my mind from the war where men awarded the Victoria Cross seemed to spend a lot of time battling the medical fraternity who seemed to have the only purpose of declaring Medically Unfit all our best people. Our top pilots, Colin Gray, Capt. Alan Ladd, Douglas Bader, and others had to fight their Medical Officer as relentlessly as they fought the war. However, the examination was conducted by Dr Caughey at the Medical school and my new wife Tania was House Surgeon under him at the time. Unfortunately, all mammalian females have a built-in urge to groom the males of the species and this at times take a bizarre twist. I undressed and lay on the usual narrow, hard and cold bench to find my large feet were displaying toenails painted fluorescent pink!

However, Caughey finally tucked his stethoscope away and said, "you're quite fit, and I don't think we'll bother to comment on the possible psychological implications of the toenails"!

When the time came we journeyed to Christchurch and attended a ceremony at the statue to Captain Robert Falcon Scott , which stands on Oxford Terrace and was sculpted by Lady Scott herself. Admiral Byrd had arrived on his way south with Operation Deepfreeze and was to lay a wreath on the Statue. It was a touching moment, the greatest American Polar explorer making tribute to the greatest British explorer. In full dress uniform, the slight figure of Byrd advanced slowly, bent, placed the wreath, and stood back and saluted as press cameras flashed and television cameras whirred. Then came a raucous American voice;

"Hey, Admiral, kin yer do all that agin?" and unbelievably Admiral Byrd picked up the wreath, stepped back and went through the whole action again, the atmosphere entirely changed. It was an insight into the power of press and television!

At Lyttleton the "Edisto" had arrived on schedule. She proved to be a fat, squat blue‑grey steel box of about 8000 tons with a cut‑a‑way bow for icebreaking, that is, her stem angled back from just above waterline so she would slide up on any ice struck, either cutting it or breaking by sheer weight. Varying numbers of her eight engines growled unceasingly below, she was always too hot below decks and reeked of a combination of food, diesel oil and cigar smoke, though not always in that order of pungency.

At Lyttleton the "Edisto" had arrived on schedule. She proved to be a fat, squat blue‑grey steel box of about 8000 tons with a cut‑a‑way bow for icebreaking, that is, her stem angled back from just above waterline so she would slide up on any ice struck, either cutting it or breaking by sheer weight. Varying numbers of her eight engines growled unceasingly below, she was always too hot below decks and reeked of a combination of food, diesel oil and cigar smoke, though not always in that order of pungency.

My bunk was a chain rack, the uppermost of three and located a scant 18 inches below a deckhead of massive steel I beams. She rolled 30 degrees in a flat calm due to her round bottom and could dip the wings of the bridge into the sea with ease when it came onto a blow. With a following sea, as a friend, Murray Robb once said, she was a screw‑arsed bitch, this being a fisherman's term for a ship which is thrown heavily first to one side then the other by the following seas.

Though I had learned to fly a plane before driving a car, my sea‑going experience at that time was limited to channel crossings, though may I say with some emphasis, he who can survive with stomach intact the Wellington‑Picton crossing in the "Tamahine" in a westerly gale has little to fear from The Horn, the Furious Fifties or any other ocean!

On deck the constant throaty growl from the exhaust, the heaving sea and flying gouts of cold spray meant little enough to romanticise over except for the passing flocks of prions and petrels and we settled down to a constant, rumble, shudder, lurch, rumble, roll, pitch typical of any motorship with a round bottom. It was not till I passed over this same ocean under the silence of sail that I realised that the ocean can be a beautiful place.

I was accorded the honorary rank of Lieutenant Commander which meant the crew addressed me as "Sir" and the officers, surprisingly, as an equal. We New Zealanders have many virtues no doubt but being kind to outsiders is not one of them and for the first time in my life I found I could even venture up on the bridge and be welcomed with a smile by the Officer on Duty or even by the Captain instead of being ordered off with a scowl. If I asked how the radar operated, or the fathometer or the twin‑crankshaft Fairbanks‑Morse 12 cylinder diesels operated, I was always met with a smile of appreciation for someone who was actually Interested, and given a good‑humoured and detailed explanation without condescension or remarks about my obvious stupidity. I learnt a good deal, not least about teaching methods.

The oceanographer, Dr Bill Littlewood, patiently explained how his bathythermographs worked and I helped string them on a cable as they were lowered, and the meteorologist explained the purpose of his airborne transmitters as they swayed aloft below a hydrogen balloon. It was actually my first acquaintance with that highly technical side of science that I was to be part of for most of my life but which at that stage had not touched New Zealand.

Americans ate, I found, almost inedible food served on a partitioned steel tray by Filipino stewards. They dished highly seasoned meaty hash there, corn‑mush here, dill pickles there, salad over there and so on and one fished about with a fork. Tea was unheard of, but excellent perked coffee was always at hand in heavy unbreakable glassy ceramic mugs. The officers were slow‑spoken and patient and most had seen war‑service along with the Petty‑officers, but few of the, mainly young, crew had. However, there were other American Army and Air‑force officers and some civilians being carried and the interservice animosity sometimes grew intense but I seemed to be accepted by all, probably because of my obvious country‑boy naivety.

On the bridge, the echo‑sounder or fathometer pinged away, recording a continuous electrostatic trace of the bottom, probably the first ever used in the Southern Ocean and after a few days the bottom dropped off the Chatham Rise down onto the South Pacific Basin which the chart showed, on the basis of random soundings made by wire, to be flat and featureless.

One day I was idly chatting to the Officer on Duty and watching the trace out of the corner of my eye, when it began to show a rise upward and move erratically towards shallower and shallower depths. I scribbled on depths and changed scales from 0-20,000ft to 0-10,000 to 0-5000 and still it rose.

"We've got a seamount!" I cried, and did some quick calculations. In fact the bottom came up 12,000ft in about twenty miles ‑ about the same as the rise to the summit of Mount Cook from the Tasman Sea. The OD even dashed out on the wing of the bridge at one point with the glasses to scan for a possible island! At about 2000ft it turned over and began to descend.

I took the unfortunate OD by the jacket and fairly shook him. "Turn this damned ship round!" I demanded. It speaks volumes for the patience of Americans, that far from being booted off the bridge, I was taken to see the Captain.

"Understand you're all excited about a seamount and want to check it out," he said kindly. "Any special reasons?"

By this time I had thought out a coherent story.

"The chart shows no such feature on the whole South Pacific Basin," I said. "It is a good 12,000ft high and has to be one of the biggest in the Southern Ocean. We almost certainly didn't come over the highest point, we should do a square search pattern, like this!" (quickly sketching on the chart.)

The "Edisto" spent much of its time doing oceanographic work and for the first time in my life, I had met a group who needed no convincing, and there were nods all round.

"I'll confer with my officers and let you know", said the Captain affably. "If we possibly can, we'll do it!"

I was called back fifteen minutes later.

"Sorry, we can't carry out your search pattern," was the verdict. "We have a tight deadline to be in McMurdo to meet four planes that are being flown down and we can't delay. But I'll tell you what we will do. I am going to send off a message to CINPAC (Commander‑in‑Chief, Pacific Fleet) in Hawaii and tell him of this seamount of yours and ask that the cargo ships coming down in two weeks all be asked to steer parallel courses to ours. That should show up how big it is!" and with that I had to be content.

A glance at any modern chart of the Southern Ocean will show the parallel tracks of the ships of Operation Deep‑Freeze One as it was called and will show that, far from being a sea‑mount, it was in fact a mighty ridge

extending from the Indian Ocean to the Pacific. And that was how I did not quite discover the Indo‑Pacific Rise! It is of course the main topographic feature of the Southern‑Ocean, and had I been more experienced I would have followed it up and published the discovery, as it was, some other Oceanographer must have finally noticed or been told of this great unexpected rise in sea bottom shown on the latest charts. A career in science is often like that!

We also had on board "Edisto" a large number of reporters and cameramen, an unscrupulous group who lived on rumour and naval telexes and whose stories sent back home bore little relationship to actual events. Sensation their newspapers wanted and sensation they got! Notable exceptions were Jack Fletcher of the National Geographic, and Fritz Goro, the well‑known "Life" cameraman. There was also WingCo. Bob Dalton, a spy like myself but from Australia, as well as Smith, the other New Zealander. The latter was an undersized career naval officer with so many medals that he carried a permanent list to port! Among them was the DSO for sinking the 44,000 ton Japanese Battlecruiser "Takao" in Singapore Harbour by midget submarine. His exploits with the legendary Alistair Mars with whom he was wont to relax with bouts of cutlass duelling, would have filled several books. In short he was the kind of fanatical, dedicated naval officer who saves the country in war but who may be lost for a purpose in life the day peace is declared!

We also had on board "Edisto" a large number of reporters and cameramen, an unscrupulous group who lived on rumour and naval telexes and whose stories sent back home bore little relationship to actual events. Sensation their newspapers wanted and sensation they got! Notable exceptions were Jack Fletcher of the National Geographic, and Fritz Goro, the well‑known "Life" cameraman. There was also WingCo. Bob Dalton, a spy like myself but from Australia, as well as Smith, the other New Zealander. The latter was an undersized career naval officer with so many medals that he carried a permanent list to port! Among them was the DSO for sinking the 44,000 ton Japanese Battlecruiser "Takao" in Singapore Harbour by midget submarine. His exploits with the legendary Alistair Mars with whom he was wont to relax with bouts of cutlass duelling, would have filled several books. In short he was the kind of fanatical, dedicated naval officer who saves the country in war but who may be lost for a purpose in life the day peace is declared!

The American officers tolerated his arrogance, they could do little else as Smith had undoubtedly sunk more Japanese fleet than some whole Task Forces! One day we were on the bridge in a rough sea and the good ship "Edisto" was lurching about, dipping the wings into the sea. One bad heave threw the unfortunate OD off balance and he skidded across the deck saving himself only by clutching a binnacle. Smith, swaying easily with hands tucked in his pea‑jacket, cocked an eye in some contempt.

"Think some of these bastards had never been to sea before, wouldn't you?" was his all too‑audible remark and the poor OD scrambled up, red‑faced.

"Why the hell don't you shut up?" I hissed, but little Smithy cared. It was already apparent we were not designed to become bosom pals. All the same, Lt.Cmdr Wilbur Smith soon had the American crew eating out of his hand; he knew how to handle Jack Tar.

"That there Commander Smith is Real Navy," said the grizzled old Chief Petty Officer when I asked why. "Now them officers we has is just boys. Goddam it, is there any action he ain't been in?"

True enough, Smith was one of those people with an ear to the ground and enough of the ear of authority to get quick transfers into anything exciting from the destroyer action in Narvik Fiord, to the hunt for the "Bismark". A walk through the lower deck was more like an inspection by Royalty. Chief Petty Officers would lurch up and salute.

"Goddam it, Commander!" and old veteran would say, "Do ah hear tell you wuz in the old ‑‑ , when the "Curacao" done got sunk?"

"That's right, Chiefy!"

"Hell, Commander! Ah wuz in the old ‑ right astern of you! When you took off across our bows after that sub, ah swear, ah could see right down your smoke stacks. You got him, Sir, didn't you?"

"We got two of them Chiefy," and it was on to the next admiring group.

They should have kept a war going specially for him!

Our first iceberg created wild excitement, it was a gleaming white flat‑top only a quarter mile across, with a waterline pocked by sea‑caves. The cameramen rushed the bridge as being the best view point and instead of being booted off they were allowed to take up the entire area and I saw the poor Captain, a shortish man, being elbowed into a corner.

In the confusion and shouting, as we closed, the command "Full Left Standard Rudder" (a curious American way of saying "Hard'a'port"), became "Full right .." as it was relayed to the helmsman, and we swung to starboard and fetched the berg a tidy clout with our bow, bringing tons of ice cascading down on our deck.

We finally drifted clear and swung seemingly out of control almost in a full circle, to the tune of audible comments from Smith about bastards who didn't seem able to steer ships. As we watched from a safer distance there was a rumble, the berg lurched and ice cascaded down.

"An avalanche!" I cried. Old Cap'n Black who had been down with Byrd before the war, chuckled.

"Easy to tell you're a mountaineer. She's calving, Boy, calving! See the bergy‑bit coming to the surface?"

Other bergs appeared and an old, dirty, weathered berg came into view on a day when "General Quarters" had been sounded, this being the American equivilent of "Action Stations". Immediately, the bad effects of the rather slack discipline on American ships became evident, the crew were simply not used to obeying orders in a hurry and there was a good deal of swearing and curses from the officers. A crewman answered back and was immediately slammed in the "Rattle" for the rest of the voyage.

The Executive Officer appeared on the bridge and glared at the dirty old berg.

"How in hell come that ship hasn't been reported by the Lookout?" he bawled and there was an embarrassed silence.

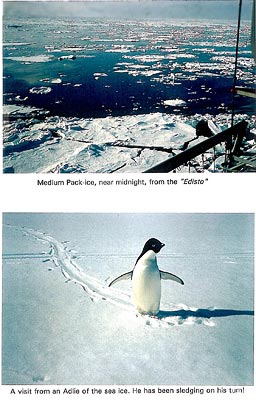

"Ice blink, my Boy!" said Cap'n Black to me next day, "See the way it lights up the sky? We'll be in the pack in a few hours!"

Oh, blessed day! The eternal roll, rumble, lurch was gone and we motored on, on 6 engines in flat calm water littered with about 5/8 pack, the ice damping out any swell. At first there were only scattered floes with a coating of new wet snow, it soon became almost solid, but mushy so that with engines growling in earnest we made continuous way at about 6 or 8 knots. Occasionally in thicker patches the bow would start to rise, and then she would subside through it, crushing her way by sheer weight and forge on. In heavy pack we slowed to only three or four knots and Cap'n Black leaned over the rail with a dip net. The ice was green underneath from the diatoms and krill were feeding, but when he offered me a raw Euphausia, for all it looked like a shrimp, I declined.

Standing on the bow, there was the sound of continuous clangs and booms of ice against the hull but amidships all was silent. Every night we had a movie in the Officer's mess and at midnight when the sun was low to the South, the floes were silhouetted sharply and sunlight reflected off the calm leads. An occasional crabeater seal woke in alarm as we bore down and Adelie penguins ran with their wobbling gait out of the way, but albatrosses and prions were no longer seen. After three days we broke through into the Ross Sea and it was the old rumble, roll, lurch again.

"Bridge says we are in sight of land!" and visible from the chilly deck were the rose‑tinted snow slopes of Erebus, one of the world's great volcanoes, with a steam cloud trailing from the 12,450ft summit. Erebus merges to the east into the lower, extinct Mt. Terror and northwards along a ridge to Cape Bird, the whole making up Ross Island.

Beaufort Island lies a few miles to the north‑west of Cape Bird and the strait between is the direct approach to McMurdo Sound, which lies between Ross Island and the mainland continent and was our goal, but an iceberg of unusual size some fifty miles long, blocked it. We passed west of Beaufort Island and saw a continuous chain of mountains, sometimes snow‑covered, sometimes bare, stretched from horizon to horizon, towering up to 13,000 feet, stark in the clear air.

"Bleak and inhospitable, my foot!" I thought. It looked wonderful country to me. The whole Sound out to Cape Bird was blocked by solid sea‑ice, possibly due to the deflection of ocean currents by the ice‑berg, and soon the "Edisto" was snarling and punching away at Fast‑ice about 6ft thick but to little avail, so we gave up and moored to the ice‑edge, ice‑anchors being run out.

The bigger ice‑breaker "Glacier" had arrived hours before and was already discharging cargo onto the ice as she had to return to the Pack to escort the cargo ships through. Helicopters clattered overhead, the first I had seen, taking important people, Admirals and such, up to view the proposed base site for the American group, at Hut Point, forty miles up the Sound.

Tracked "Weasels" painted bright orange ran about. They were designed to be used on mudflats in the War but could be used on snow. Adelie penguins streamed over from the rookery on Cape Bird to inspect the visitors and seamen ran about in ridiculous fashion trying to catch them. A group from "Glacier" began walking towards Cape Bird and soon found themselves in loose pack and in danger of going out to sea. Hooters sounded and loud hailers ordered them back. The sun was bright and the day warm, possibly above freezing.

The "Edisto" began swinging cargo onto the ice for the first over‑ice journey to Hut Point. The first to go were to be a party of oceanographers, to make a detailed map of the place, a Search and Rescue team to which I had been attached, and a General Support Group. Not knowing better and seeing work to be done, I dropped over the side to help the crew stack cargo for loading on sleds and intercept sleds, tents and gear for our Search and rescue group. As usual the crew were inept teenagers with no officer or Chief in sight, and I soon called a halt.

"Lets get a bit of order in this," said I. "We can't have unrelated stuff arriving on the same sleds, it'll never be found. Lets put all Oceanographic stuff in this pile, all Rescue Squad gear here and Support gear here by this flag!" Soon seamen were staggering up.

"Hey, Sir, where do I put this?"

Some boxes had labels torn off and I had to bar cases open to identify the contents. Other civilians stood idly by the rail taking photographs as about twenty tons of cargo came ashore and we loaded the sorted stacks onto 4 sleds behind two D2 tractors for the over‑ice journey. At least when they arrived it would not be necessary to search every sledge to find a box.

A Weasel with Cmdr Whitney, a tall, greying, responsible officer, set off to flag a route up the sound, the helicopter having reported a 4ft‑wide tide crack in the ice extending out from Cape Royds, about 15 miles up the Sound.

Back aboard a crewman came up.

"Sir, Cap'n asks me to thank y'all for the work you did unloading and taking charge n' all!" Why no officer or petty officer had been detailed to supervise I never found out but I soon found that virtually all civilians expected to be waited on and to do nothing in return.

Obviously from now on the action was to be on shore and I had cultivated acquaintance with the Search and Rescue Group, consisting of Lt. Don Tuck who was to be in charge of the Pole Station, Lt. Dave Baker, and Sgt. Tom McEvoy who had some 13 winters to his credit in the Arctic. They had with them a dozen husky dogs and had been given practice in parachuting. The dogs were a light New Hampshire breed never meant for serious sledging, about half the weight of a real husky, but as the helicopters of the day could not land above about 3000ft, in case of a crash, rescue would have to rely on dogs! The rescue team had about 2000lbs of gear piled up, including boxes of iron pitons!

"Y'know, Dave," I said, "We can't expect the dogs to move two sleds and all this junk, they won't be fit straight off the ship, why don't we dump half of it on a tractor sled?"

But Baker wanted to be independent, and I, not really knowing better, gave way. Stubbornness is a virtue that should be more appreciated.

Baker was flown out to Hut Point in a clattering helicopter to see where we were going and see our route and came back looking grave.

"Hut Point is a miserable hole," he said, "Twelve degrees colder than here, just black rocks and snow!"

When packed the two sleds had over a thousand pounds on each. They were not Nansens or Komatiks but a heavy Alaskan type without handle bars, but with a pole angling up at front by which the driver was supposed to swing it around obstructions, called a "Gee Pole". One couldn't ski beside such a sled without handle‑bars: I suspect the driver was meant to run like hell on snow‑shoes.

Old Cap'n Black fussed about checking dog harnesses, which were complicated, and the poor dogs were held to a centre trace both front and rear so they could not change places. We set off through a covey of photographers both amateur and professional, a real dog team setting off over the Antarctic ice being a shot no one could miss and something the most unimaginative reporter could turn into a headline.

The first dash quickly slowed to a walk and the dogs strained against the ridiculously heavy load. Luckily, because in my ignorance I was wearing heavy boots not light mukluks and one couldn't ski without handlebars and a handline to hang onto.

It was calm and sunny, Erebus steamed quietly ahead on our left, and a geyser on the flank periodically jetted boiling water and steam. On our right, eighty miles away, the Royal Society Range lofted to 13,000 feet while ahead sea‑ice extended, now flat, now ridged by pressure or cut by leads along which Weddell seals dozed, oblivious of any possible enemy.

The sun grew hotter and I tucked my anorak into a lashline on a sled and sang!

©2007 - may not be reproduced without permission